Trade-offs: The Production Possibility Frontier

The first principle of economics introduced in Chapter 1 is that resources are scarce and that, as a result, any economy—whether it’s an isolated group of a few dozen hunter-gatherers or the 6 billion people making up the twenty-first-century global economy—faces trade-offs. No matter how lightweight the Boeing Dreamliner is, no matter how efficient Boeing’s assembly line, producing Dreamliners means using resources that therefore can’t be used to produce something else.

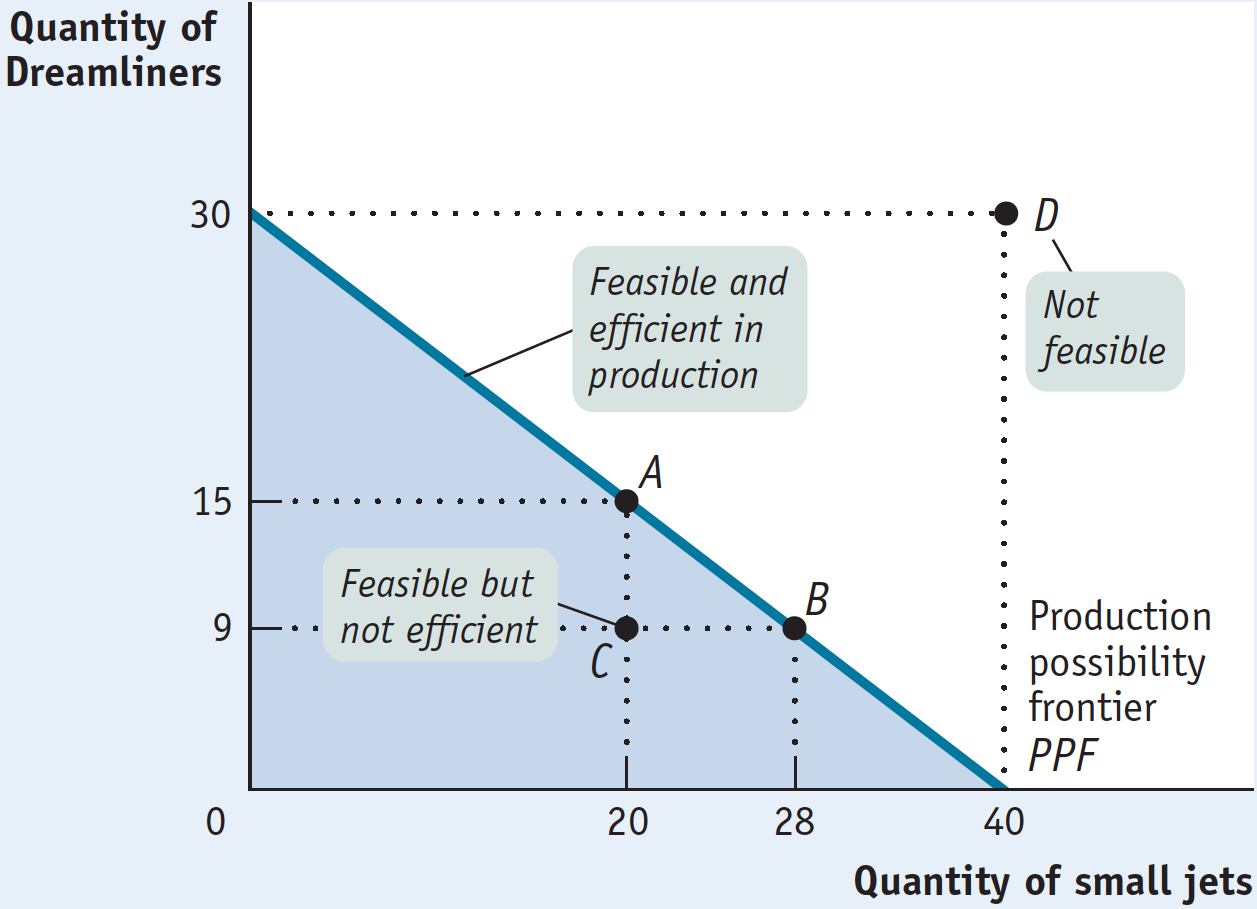

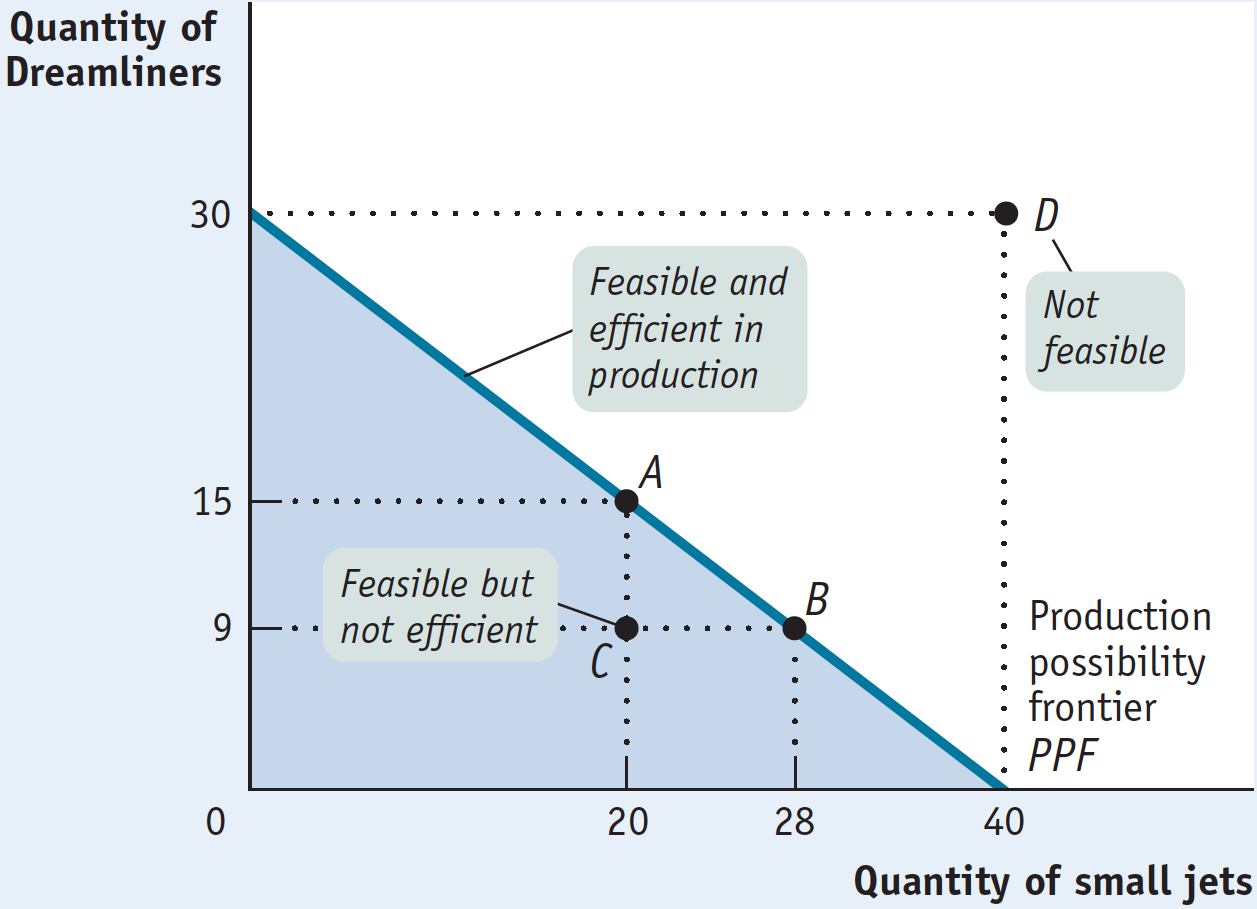

The production possibility frontier illustrates the trade-offs facing an economy that produces only two goods. It shows the maximum quantity of one good that can be produced for any given quantity produced of the other.

To think about the trade-offs that face any economy, economists often use the model known as the production possibility frontier. The idea behind this model is to improve our understanding of trade-offs by considering a simplified economy that produces only two goods. This simplification enables us to show the trade-off graphically.

Suppose, for a moment, that the United States was a one-company economy, with Boeing its sole employer and aircraft its only product. But there would still be a choice of what kinds of aircraft to produce—say, Dreamliners versus small commuter jets. Figure 2-1 shows a hypothetical production possibility frontier representing the trade-off this one-company economy would face. The frontier—the line in the diagram—shows the maximum quantity of small jets that Boeing can produce per year given the quantity of Dreamliners it produces per year, and vice versa. That is, it answers questions of the form, “What is the maximum quantity of small jets that Boeing can produce in a year if it also produces 9 (or 15, or 30) Dreamliners that year?”

The Production Possibility Frontier The production possibility frontier illustrates the trade-offs Boeing faces in producing Dreamliners and small jets. It shows the maximum quantity of one good that can be produced given the quantity of the other good produced. Here, the maximum quantity of Dreamliners manufactured per year depends on the quantity of small jets manufactured that year, and vice versa. Boeing’s feasible production is shown by the area inside or on the curve. Production at point C is feasible but not efficient. Points A and B are feasible and efficient in production, but point D is not feasible.

There is a crucial distinction between points inside or on the production possibility frontier (the shaded area) and outside the frontier. If a production point lies inside or on the frontier—like point C, at which Boeing produces 20 small jets and 9 Dreamliners in a year—it is feasible. After all, the frontier tells us that if Boeing produces 20 small jets, it could also produce a maximum of 15 Dreamliners that year, so it could certainly make 9 Dreamliners.

However, a production point that lies outside the frontier—such as the hypothetical production point D, where Boeing produces 40 small jets and 30 Dreamliners—isn’t feasible. Boeing can produce 40 small jets and no Dreamliners, or it can produce 30 Dreamliners and no small jets, but it can’t do both.

In Figure 2-1 the production possibility frontier intersects the horizontal axis at 40 small jets. This means that if Boeing dedicated all its production capacity to making small jets, it could produce 40 small jets per year but could produce no Dreamliners. The production possibility frontier intersects the vertical axis at 30 Dreamliners. This means that if B oeing dedicated all its production capacity to making Dreamliners, it could produce 30 Dreamliners per year but no small jets.

The figure also shows less extreme trade-offs. For example, if Boeing’s managers decide to make 20 small jets this year, they can produce at most 15 Dreamliners; this production choice is illustrated by point A. And if Boeing’s managers decide to produce 28 small jets, they can make at most 9 Dreamliners, as shown by point B.

Thinking in terms of a production possibility frontier simplifies the complexities of reality. The real-world U.S. economy produces millions of different goods. Even Boeing can produce more than two different types of planes. Yet it’s important to realize that even in its simplicity, this stripped-down model gives us important insights about the real world.

By simplifying reality, the production possibility frontier helps us understand some aspects of the real economy better than we could without the model: efficiency, opportunity cost, and economic growth.

Efficiency First of all, the production possibility frontier is a good way to illustrate the general economic concept of efficiency. Recall from Chapter 1 that an economy is efficient if there are no missed opportunities—there is no way to make some people better off without making other people worse off.

One key element of efficiency is that there are no missed opportunities in production—there is no way to produce more of one good without producing less of other goods. As long as Boeing operates on its production possibility frontier, its production is efficient. At point A, 15 Dreamliners are the maximum quantity feasible given that Boeing has also committed to producing 20 small jets; at point B, 9 Dreamliners are the maximum number that can be made given the choice to produce 28 small jets; and so on.

But suppose for some reason that Boeing was operating at point C, making 20 small jets and 9 Dreamliners. In this case, it would not be operating efficiently and would therefore be inefficient: it could be producing more of both planes.

Although we have used an example of the production choices of a one-firm, two-good economy to illustrate efficiency and inefficiency, these concepts also carry over to the real economy, which contains many firms and produces many goods. If the economy as a whole could not produce more of any one good without producing less of something else—that is, if it is on its production possibility frontier—then we say that the economy is efficient in production.

If, however, the economy could produce more of some things without producing less of others—which typically means that it could produce more of everything—then it is inefficient in production. For example, an economy in which large numbers of workers are involuntarily unemployed is clearly inefficient in production. And that’s a bad thing, because the economy could be producing more useful goods and services.

Although the production possibility frontier helps clarify what it means for an economy to be efficient in production, it’s important to understand that efficiency in production is only part of what’s required for the economy as a whole to be efficient. Efficiency also requires that the economy allocate its resources so that consumers are as well off as possible. If an economy does this, we say that it is efficient in allocation.

Our imaginary one-company economy is efficient if it (1) produces as many small jets as it can given the production of Dreamliners, and (2) if it produces the mix of small and large planes that people want to consume.

istockphoto

To see why efficiency in allocation is as important as efficiency in production, notice that points A and B in Figure 2-1 both represent situations in which the economy is efficient in production, because in each case it can’t produce more of one good without producing less of the other. But these two situations may not be equally desirable from society’s point of view. Suppose that society prefers to have more small jets and fewer Dreamliners than at point A; say, it prefers to have 28 small jets and 9 Dreamliners, corresponding to point B. In this case, point A is inefficient in allocation from the point of view of the economy as a whole because it would rather have Boeing produce at point B rather than at point A.

This example shows that efficiency for the economy as a whole requires both efficiency in production and efficiency in allocation: to be efficient, an economy must produce as much of each good as it can given the production of other goods, and it must also produce the mix of goods that people want to consume. And it must also deliver those goods to the right people: an economy that gives small jets to international airlines and Dreamliners to commuter airlines serving small rural airports is inefficient, too.

In the real world, command economies, such as the former Soviet Union, are notorious for inefficiency in allocation. For example, it was common for consumers to find stores well stocked with items few people wanted but lacking such basics as soap and toilet paper.