Comparative Advantage versus Absolute Advantage

It’s easy to accept the idea that Vietnam and Thailand have a comparative advantage in shrimp production: they have a tropical climate that’s better suited to shrimp farming than that of the United States (even along the Gulf Coast), and they have a lot of usable coastal area. So the United States imports shrimp from Vietnam and Thailand. In other cases, however, it may be harder to understand why we import certain goods from abroad.

U.S. imports of phones from China are a case in point. There’s nothing about China’s climate or resources that makes it especially good at assembling electronic devices. In fact, it almost surely would take fewer hours of labor to assemble a smartphone or a tablet in the United States than in China.

Why, then, do we buy phones assembled in China? Because the gains from trade depend on comparative advantage, not absolute advantage. Yes, it would take less labor to assemble a phone in the United States than in China. That is, the productivity of Chinese electronics workers is less than that of their U.S. counterparts. But what determines comparative advantage is not the amount of resources used to produce a good but the opportunity cost of that good—

Here’s how it works: Chinese workers have low productivity compared with U.S. workers in the electronics industry. But Chinese workers have even lower productivity compared with U.S. workers in other industries. Because Chinese labor productivity in industries other than electronics is relatively very low, producing a phone in China, even though it takes a lot of labor, does not require forgoing the production of large quantities of other goods.

In the United States, the opposite is true: very high productivity in other industries (such as automobiles) means that assembling electronic products in the United States, even though it doesn’t require much labor, requires sacrificing lots of other goods. So the opportunity cost of producing electronics is less in China than in the United States. Despite its lower labor productivity, China has a comparative advantage in the production of many consumer electronics, although the United States has an absolute advantage.

The source of China’s comparative advantage in consumer electronics is reflected in global markets by the wages Chinese workers are paid. That’s because a country’s wage rates, in general, reflect its labor productivity. In countries where labor is highly productive in many industries, employers are willing to pay high wages to attract workers, so competition among employers leads to an overall high wage rate. In countries where labor is less productive, competition for workers is less intense and wage rates are correspondingly lower.

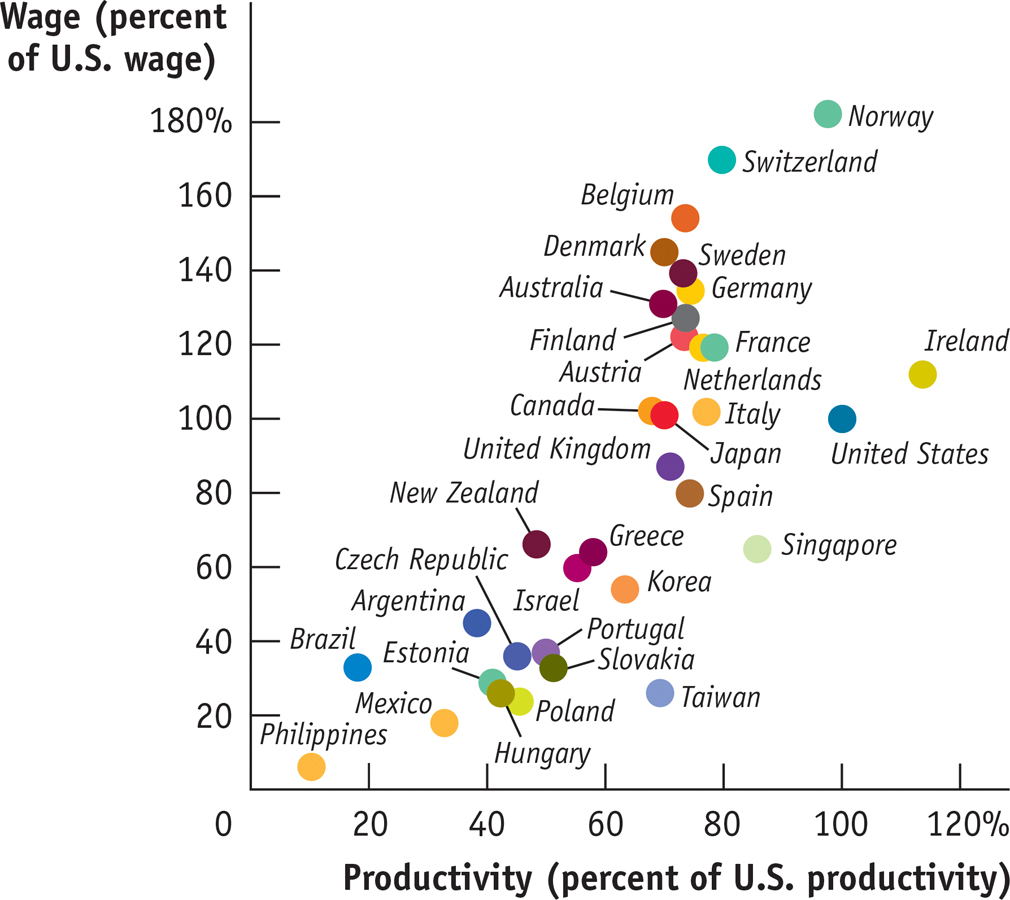

As the accompanying Global Comparison shows, there is indeed a strong relationship between overall levels of productivity and wage rates around the world. Because China has generally low productivity, it has a relatively low wage rate. Low wages, in turn, give China a cost advantage in producing goods where its productivity is only moderately low, like consumer electronics. As a result, it’s cheaper to produce these goods in China than in the United States.

Productivity and Wages Around the World

Is it true that both the pauper labor argument and the sweatshop labor argument are fallacies? Yes, it is. The real explanation for low wages in poor countries is low overall productivity.

The graph shows estimates of labor productivity, measured by the value of output (GDP) per worker, and wages, measured by the hourly compensation of the average worker, for several countries in 2012. Both productivity and wages are expressed as percentages of U.S. productivity and wages; for example, productivity and wages in Japan were 70% and 101%, respectively, of their U.S. levels. You can see the strong positive relationship between productivity and wages. The relationship isn’t perfect. For example, Norway has higher wages than its productivity might lead you to expect. But simple comparisons of wages give a misleading sense of labor costs in poor countries: their low wage advantage is mostly offset by low productivity.

Sources The Conference Board; Penn World Table 8.0.

The kind of trade that takes place between low-

Both fallacies miss the nature of gains from trade: it’s to the advantage of both countries if the poorer, lower-

It’s particularly important to understand that buying a good made by someone who is paid much lower wages than most U.S. workers doesn’t necessarily imply that you’re taking advantage of that person. It depends on the alternatives. Because workers in poor countries have low productivity across the board, they are offered low wages whether they produce goods exported to America or goods sold in local markets. A job that looks terrible by rich-

International trade that depends on low-