What Real GDP Doesn’t Measure

GDP per capita is GDP divided by the size of the population; it is equivalent to the average GDP per person.

GDP, nominal or real, is a measure of a country’s aggregate output. Other things equal, a country with a larger population will have higher GDP simply because there are more people working. So if we want to compare GDP across countries but want to eliminate the effect of differences in population size, we use the measure GDP per capita—GDP divided by the size of the population, equivalent to the average GDP per person.

Real GDP per capita can be a useful measure in some circumstances, such as in a comparison of labor productivity between countries. However, despite the fact that it is a rough measure of the average real output per person, real GDP per capita has well-

Let’s take a moment to be clear about why a country’s real GDP per capita is not a sufficient measure of human welfare in that country and why growth in real GDP per capita is not an appropriate policy goal in itself.

GDP and the Meaning of Life

“I’ve been rich and I’ve been poor,” the actress Mae West famously declared. “Believe me, rich is better.” But is the same true for countries?

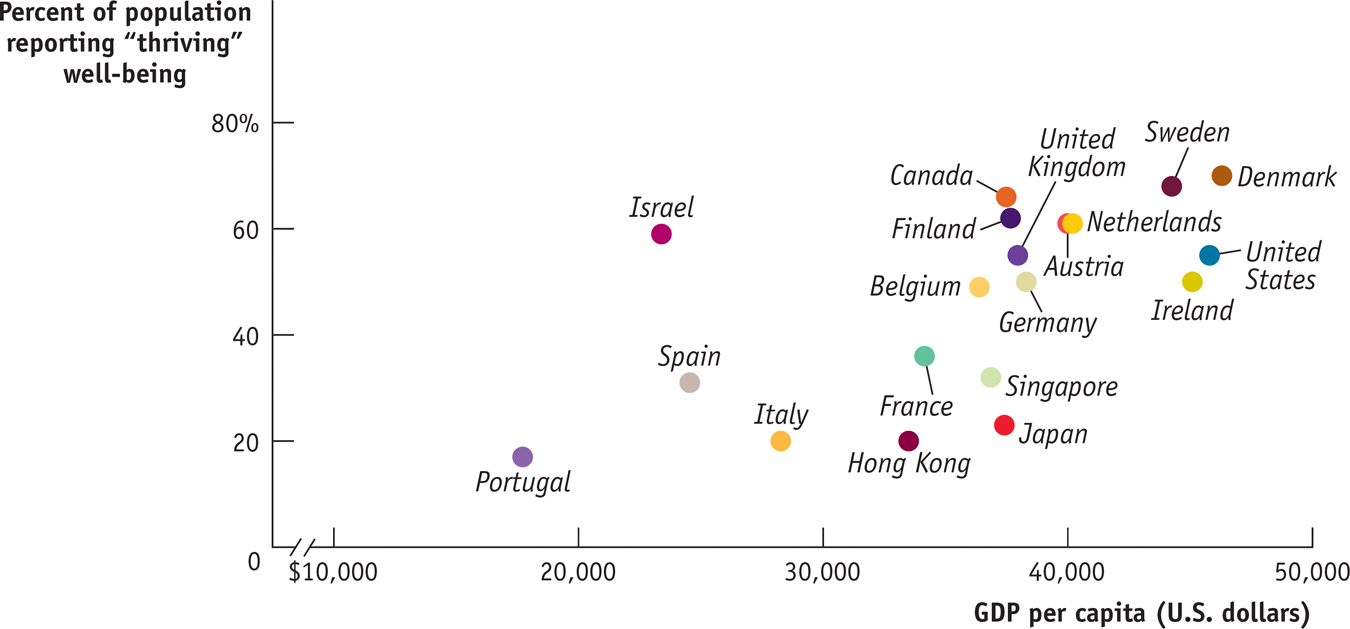

This figure shows two pieces of information for a number of countries: how rich they are, as measured by GDP per capita, and how people assess their well-

Rich is better. Richer countries on average have higher well-

being than poor countries. Money matters less as you grow richer. As GDP rises, the average gain in life satisfaction gets smaller and smaller. For example, the rise in GDP per capita from lower-

income Italy to middle- income Belgium is about the same as from middle- income Belgium to the high- income United States. But the increase in life satisfaction is much greater going from Italy to Belgium compared to going from Belgium to the United States. Money isn’t everything. Israelis, though rich by world standards, are poorer than Americans—

but they seem more satisfied with their lives. Japan is richer than most other nations, but by and large quite miserable.

These results are consistent with the observation that high GDP per capita makes it easier to achieve a good life but that countries aren’t equally successful in taking advantage of that possibility.

Source: Gallup; World Bank.

One way to think about this issue is to say that an increase in real GDP means an expansion in the economy’s production possibility frontier. Because the economy has increased its productive capacity, society can achieve more things. But whether society actually makes good use of that increased potential to improve living standards is another matter. To put it in a slightly different way, your income may be higher this year than last year, but whether you use that higher income to improve your quality of life is your choice.

So let’s say it again: real GDP per capita is a measure of an economy’s average aggregate output per person—

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Miracle in Venezuela?

Miracle in Venezuela?

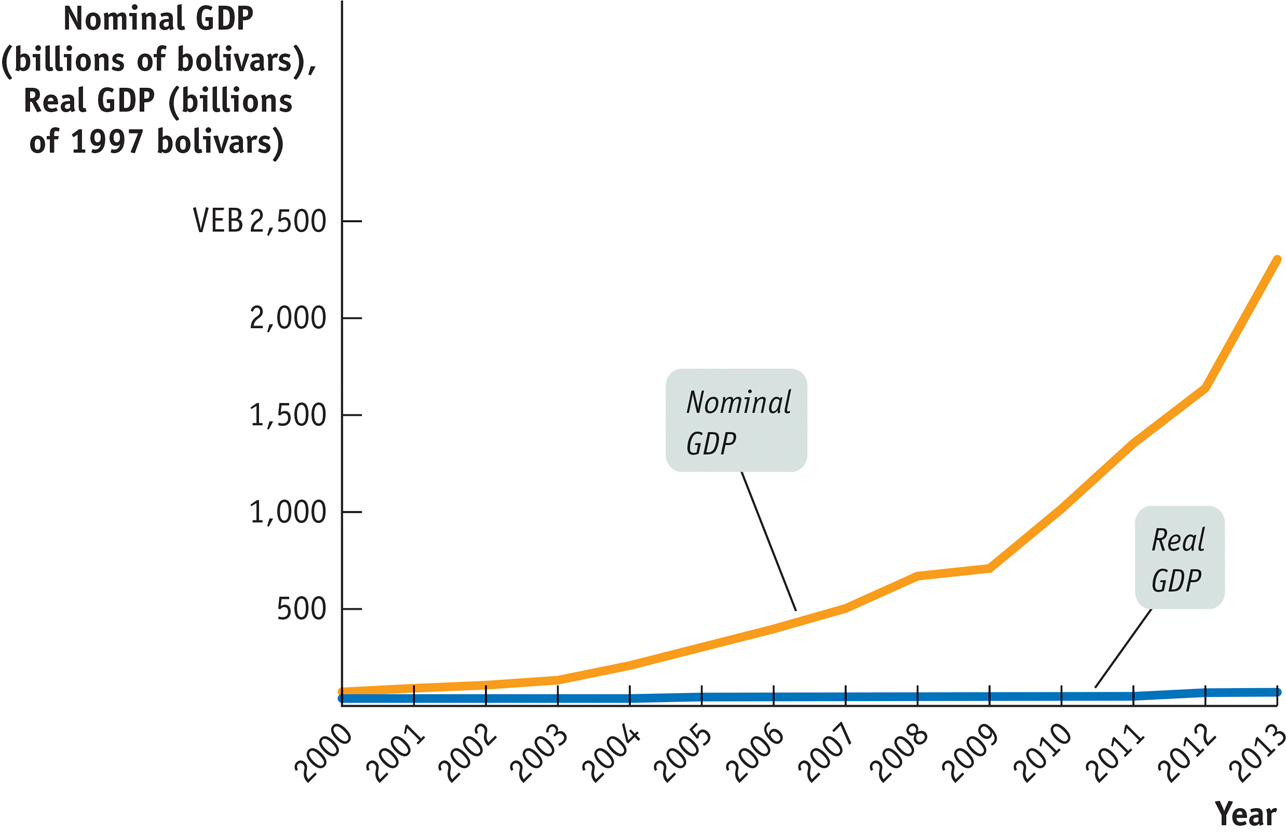

The South American nation of Venezuela has a distinction that may surprise you: in recent years, it has had one of the world’s fastest-

So is Venezuela experiencing an economic miracle? No, it’s just suffering from unusually high inflation. Figure 7-4 shows Venezuela’s nominal and real GDP from 2000 to 2013, with real GDP measured in 1997 prices. Real GDP did grow over the period, but at an annual rate of only 3.2%. That’s about twice the U.S. growth rate over the same period, but it is far short of China’s 10% growth.

Quick Review

To determine the actual growth in aggregate output, we calculate real GDP using prices from some given base year. In contrast, nominal GDP is the value of aggregate output calculated with current prices. U.S. statistics on real GDP are always expressed in chained dollars.

Real GDP per capita is a measure of the average aggregate output per person. But it is not a sufficient measure of human welfare, nor is it an appropriate goal in itself, because it does not reflect important aspects of living standards within an economy.

7-2

Question 7.4

Assume there are only two goods in the economy, french fries and onion rings. In 2013, 1,000,000 servings of french fries were sold at $0.40 each and 800,000 servings of onion rings at $0.60 each. From 2013 to 2014, the price of french fries rose by 25% and the servings sold fell by 10%; the price of onion rings fell by 15% and the servings sold rose by 5%.

Calculate nominal GDP in 2013 and 2014. Calculate real GDP in 2014 using 2013 prices.

Why would an assessment of growth using nominal GDP be misguided?

Question 7.5

From 2005 to 2010, the price of electronic equipment fell dramatically and the price of housing rose dramatically. What are the implications of this in deciding whether to use 2005 or 2010 as the base year in calculating 2013 real GDP?

Solutions appear at back of book.