Frictional Unemployment

When a worker loses a job involuntarily due to job destruction, he or she often doesn’t take the first new job offered. For example, suppose a skilled programmer, laid off because her software company’s product line was unsuccessful, sees a help-

Workers who spend time looking for employment are engaged in job search.

Economists say that workers who spend time looking for employment are engaged in job search. If all workers and all jobs were alike, job search wouldn’t be necessary; if information about jobs and workers was perfect, job search would be very quick. In practice, however, it’s normal for a worker who loses a job, or a young worker seeking a first job, to spend at least a few weeks searching.

Frictional unemployment is unemployment due to the time workers spend in job search.

Frictional unemployment is unemployment due to the time workers spend in job search. A certain amount of frictional unemployment is inevitable due to the constant process of economic change. Thus even in 2007, a year of low unemployment, there were 62 million “job separations,” in which workers left or lost their jobs. Total employment grew because these separations were more than offset by more than 63 million hires. Inevitably, some of the workers who left or lost their jobs spent at least some time unemployed, as did some of the workers newly entering the labor force.

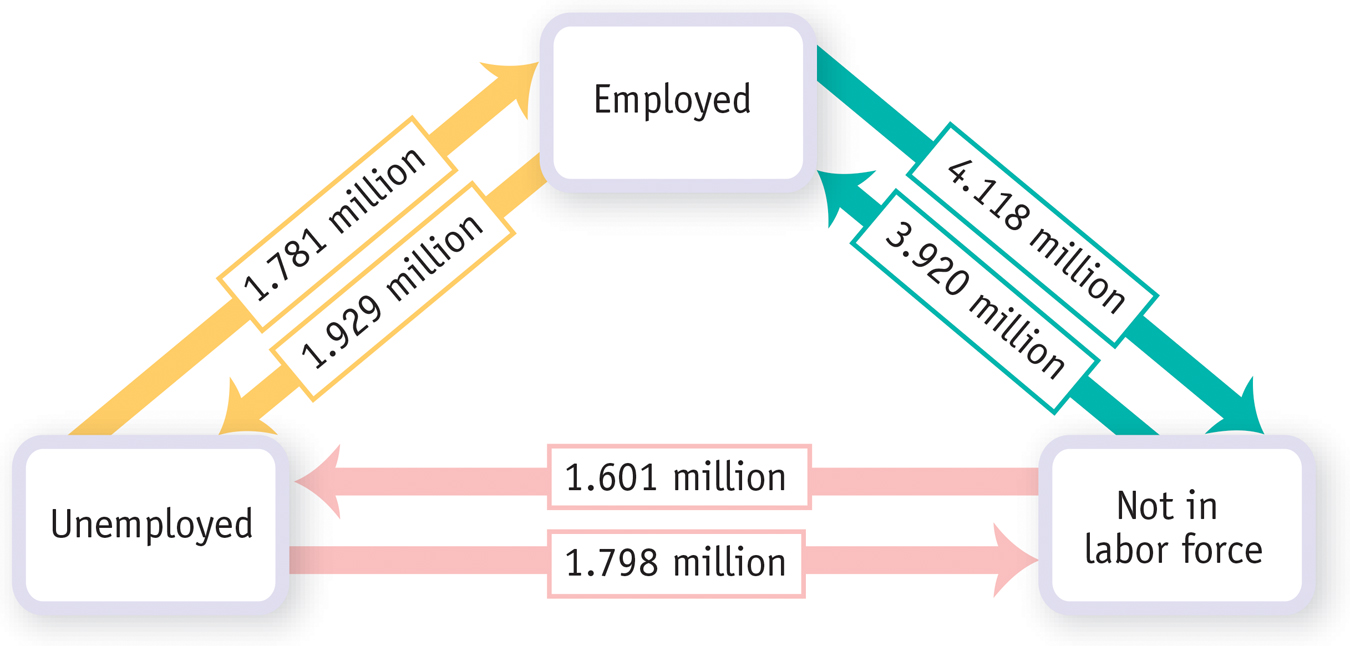

Figure 8-7 shows the average monthly flows of workers among three states: employed, unemployed, and not in the labor force during 2007, a year of relatively low unemployment. What the figure suggests is how much churning is constantly taking place in the labor market. An inevitable consequence of that churning is a significant number of workers who haven’t yet found their next job—

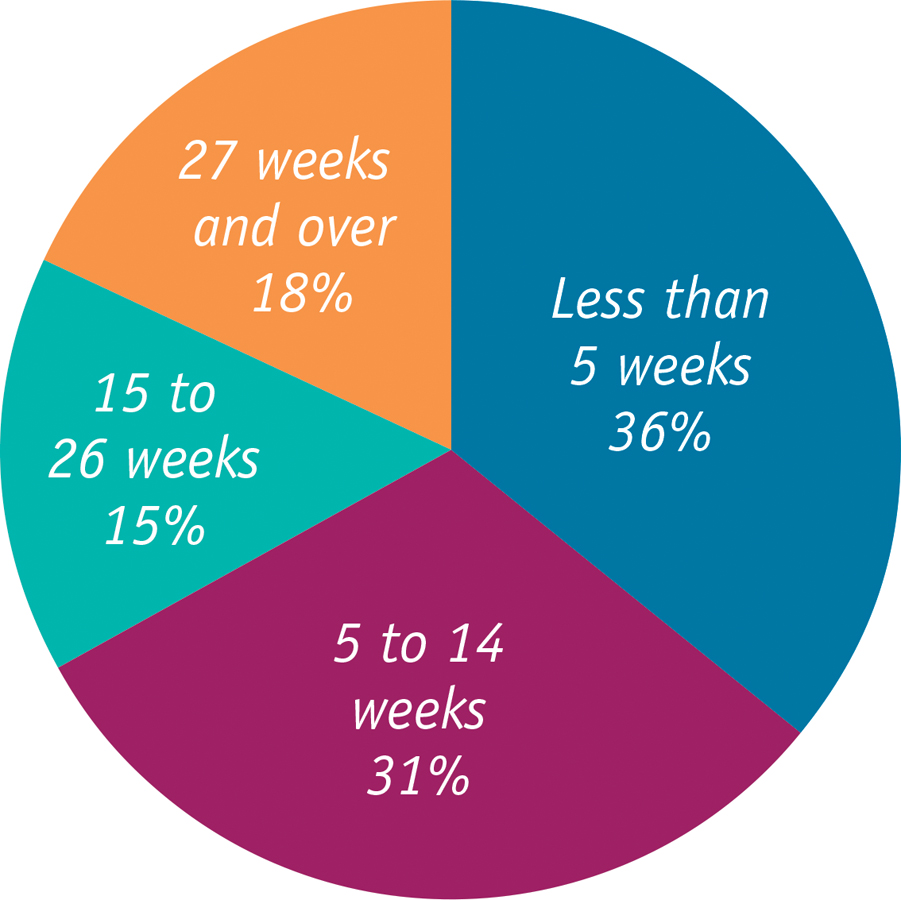

A limited amount of frictional unemployment is relatively harmless and may even be a good thing. The economy is more productive if workers take the time to find jobs that are well matched to their skills, and workers who are unemployed for a brief period while searching for the right job don’t experience great hardship. In fact, when there is a low unemployment rate, periods of unemployment tend to be quite short, suggesting that much of the unemployment is frictional.

Figure 8-8 shows the composition of unemployment for all of 2007, when the unemployment rate was only 4.6%. Thirty-

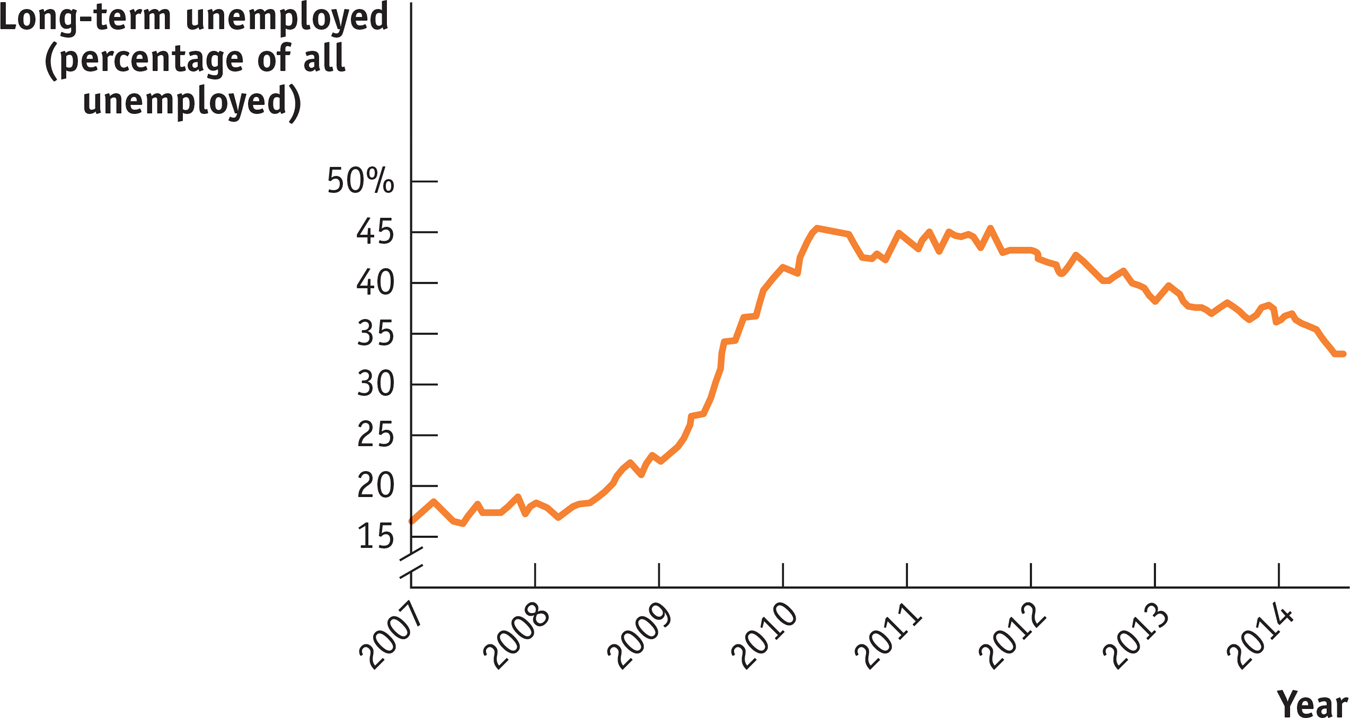

In periods of higher unemployment, however, workers tend to be jobless for longer periods of time, suggesting that a smaller share of unemployment is frictional. Figure 8-9 shows the fraction of the unemployed who had been out of work for six months or more from 2007 to mid-