Real GDP per Capita

The key statistic used to track economic growth is real GDP per capita—

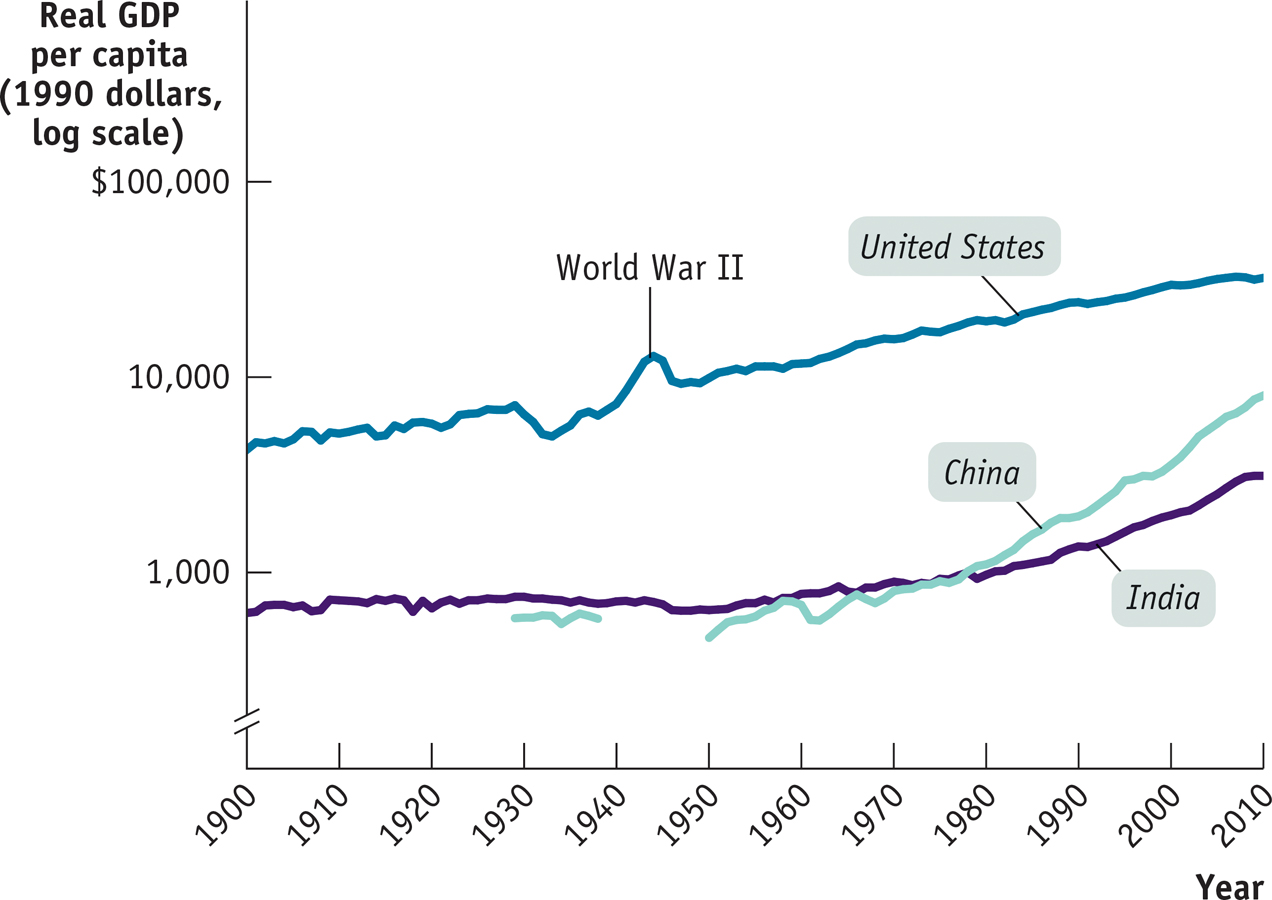

Although we also learned in Chapter 7 that growth in real GDP per capita should not be a policy goal in and of itself, it does serve as a very useful summary measure of a country’s economic progress over time. Figure 9-1 shows real GDP per capita for the United States, India, and China, measured in 1990 dollars, from 1900 to 2010. (We’ll talk about India and China in a moment.) The vertical axis is drawn on a logarithmic scale so that equal percent changes in real GDP per capita across countries are the same size in the graph.

To give a sense of how much the U.S. economy grew during the last century, Table 9-1 shows real GDP per capita at selected years, expressed two ways: as a percentage of the 1900 level and as a percentage of the 2010 level. In 1920, the U.S. economy already produced 136% as much per person as it did in 1900. In 2010, it produced 758% as much per person as it did in 1900, an almost eightfold increase. Alternatively, in 1900 the U.S. economy produced only 13% as much per person as it did in 2010.

|

Year |

Percentage of 1900 real GDP per capita |

Percentage of 2010 real GDP per capita |

|---|---|---|

|

1900 |

100% |

13% |

|

1920 |

136 |

18 |

|

1940 |

171 |

23 |

|

1980 |

454 |

60 |

|

2000 |

696 |

92 |

|

2010 |

758 |

100 |

|

Sources: Angus Maddison, Statistics on World Population, GDP, and Per Capita GDP, 1– |

||

TABLE 9-

The income of the typical family normally grows more or less in proportion to per capita income. For example, a 1% increase in real GDP per capita corresponds, roughly, to a 1% increase in the income of the median or typical family—

Yet many people in the world have a standard of living equal to or lower than that of the United States at the beginning of the last century. That’s the message about China and India in Figure 9-1: despite dramatic economic growth in China over the last three decades and the less dramatic acceleration of economic growth in India, China has only recently exceeded the standard of living that the United States enjoyed in the early twentieth century, while India is still poorer than the United States was at that time. And much of the world today is poorer than China or India.

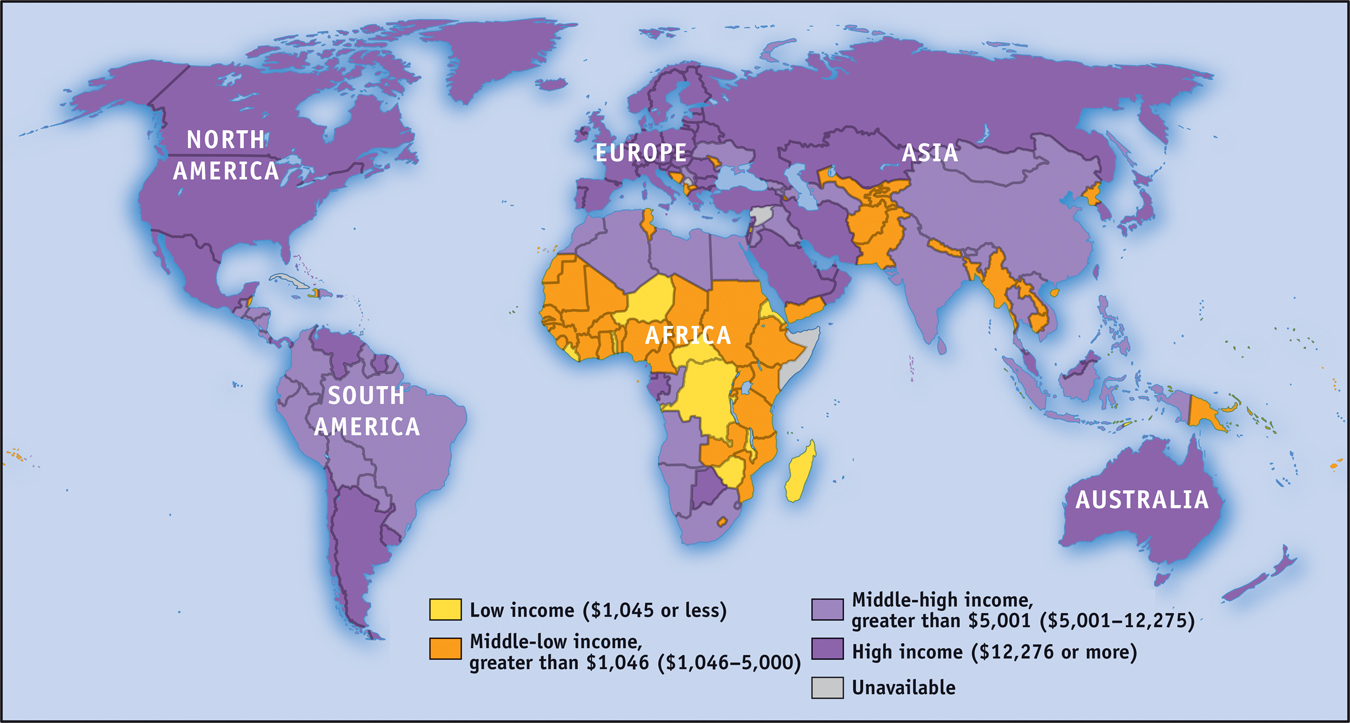

You can get a sense of how poor much of the world remains by looking at Figure 9-2, a map of the world in which countries are classified according to their 2013 levels of GDP per capita, in U.S. dollars. As you can see, large parts of the world have very low incomes. Generally speaking, the countries of Europe and North America, as well as a few in the Pacific, have high incomes. The rest of the world, containing most of its population, is dominated by countries with GDP less than $5,000 per capita—

PITFALLS: CHANGE IN LEVELS VERSUS RATE OF CHANGE

CHANGE IN LEVELS VERSUS RATE OF CHANGE

When studying economic growth, it’s vitally important to understand the difference between a change in level and a rate of change. When we say that real GDP “grew,” we mean that the level of real GDP increased. For example, we might say that U.S. real GDP grew during 2013 by $297 billion.

If we knew the level of U.S. real GDP in 2012, we could also represent the amount of 2013 growth in terms of a rate of change. For example, if U.S. real GDP in 2012 had been $15,470 billion, then U.S. real GDP in 2013 would have been $15,470 billion + $297 billion = $15,767 billion. We could calculate the rate of change, or the growth rate, of U.S. real GDP during 2013 as: (($15,767 billion − $15,470 billion)/$15,470 billion) × 100 = $297 billion/$15,470 billion) × 100 = 1.92%. Statements about economic growth over a period of years almost always refer to changes in the growth rate.

When talking about growth or growth rates, economists often use phrases that appear to mix the two concepts and so can be confusing. For example, when we say that “U.S. growth fell during the 1970s,” we are really saying that the U.S. growth rate of real GDP was lower in the 1970s in comparison to the 1960s. When we say that “growth accelerated during the early 1990s,” we are saying that the growth rate increased year after year in the early 1990s—