1.2 Module 2: Models and the Circular Flow

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

Why models are an important tool in the study of economics

Why models are an important tool in the study of economics

How to interpret the circular-flow diagram of the economy

How to interpret the circular-flow diagram of the economy

How individual decisions affect the larger economy

How individual decisions affect the larger economy

In the section opener, you saw how the Wright brothers’ experimenting with a miniature airplane in a wind tunnel—a simplified representation of the real thing—served as a very useful model of a flying plane. In this module, we will look at why models are so useful to economists. We’ll also examine one important simplified representation of economic reality—the circular-flow diagram.

Models Take Flight in Economics

A model is a simplified representation used to better understand a real-world situation.

A model is any simplified version of reality that is used to better understand real-world situations. But how do we create a simplified representation of an economic situation?

One possibility—an economist’s equivalent of a wind tunnel—is to find or create a real but simplified economy. For example, economists interested in the economic role of money have studied the system of exchange that developed in World War II prison camps, in which cigarettes became a universally accepted form of payment, even among prisoners who didn’t smoke.

Another possibility is to simulate the workings of the economy on a computer. For example, when changes in tax law are proposed, government officials use tax models—large mathematical computer programs—to assess how the proposed changes would affect different groups of people.

The other things equal assumption means that all other relevant factors remain unchanged. This is also known as the ceteris paribus assumption.

Models are important because their simplicity allows economists to focus on the effects of only one change at a time. That is, they allow us to hold everything else constant and to study how one change affects the overall economic outcome. So when building economic models, an important assumption is the other things equal assumption, which means that all other relevant factors remain unchanged. Sometimes the Latin phrase ceteris paribus, which means “other things equal,” is used.

But it isn’t always possible to find or create a small-scale version of the whole economy, and a computer program is only as good as the data it uses. (Programmers have a saying: garbage in, garbage out.) For many purposes, the most effective form of economic modeling is the construction of “thought experiments”: simplified, hypothetical versions of real-world situations.

As you will see throughout this book, economists’ models are often in the form of a graph. In Module 3 we will look at graphs of the production possibility frontier, a model that helps economists think about the choices made in every economy. In Module 4 we turn to comparative advantage, a model that clarifies the principle of gains from trade—trade both between individuals and between countries. Models can also be represented in diagrams. In this module we will use the circular-flow diagram to better understand the workings of the economy.

THE MODEL THAT ATE THE ECONOMY

A model is just a model, right? So how much damage can it do? Economists probably would have answered that question differently before the financial meltdown of 2008–2009 than after it. It turns out that a bad economic model played a significant role in the origins of the crisis.

“The model that ate the economy” originated in finance theory, the branch of economics that seeks to understand what assets like stocks and bonds are worth. Financial theorists often devise complex mathematical models to help investment companies decide what assets to buy and sell and at what price.

Finance theory has become increasingly important as Wall Street (a district in New York City where nearly all major investment companies have their headquarters) has shifted from trading simple assets like stocks and bonds to more complex assets—notably, mortgage-backed securities (or MBSs for short). An MBS is an asset that entitles its owner to a stream of earnings based on the payments made by thousands of people on their home loans. Investors wanted to know how risky these complex assets were. That is, how likely was it that an investor would lose money on an MBS?

Although we won’t go into the details, estimating the likelihood of losing money on an MBS is a complicated problem. It involves calculating the probability that a significant number of the thousands of homeowners backing your security will stop paying their mortgages. Until that probability could be calculated, investors didn’t want to buy MBSs.

In 2000, a Wall Street financial theorist announced that he had solved the problem by devising a simple model for estimating the risk of buying an MBS. Financial traders loved the model, as it opened up a huge and extraordinarily profitable market for them. Using this simple model, Wall Street was able to create and sell billions of MBSs, generating billions in profits for itself.

Or investors thought they had calculated the risk of losing money on an MBS. Some financial experts warned from the sidelines that the estimates of risk calculated by this simple model were just plain wrong. They said that in the search for simplicity, the model underestimated the likelihood that many homeowners would stop paying their mortgages at the same time, leaving MBS investors in danger of incurring huge losses.

Billions of dollars worth of MBSs were sold to investors both in the United States and abroad. In 2008–2009, the problems critics warned about exploded in catastrophic fashion. Over the previous decade, American home prices had risen too high, and mortgages had been extended to many who were unable to pay. As home prices fell, millions of homeowners didn’t pay their mortgages. With losses mounting for MBS investors, it became all too clear that the model had indeed underestimated the risks. When investors and financial institutions around the world realized the extent of their losses, the worldwide economy ground to an abrupt halt.

The Circular-Flow Diagram

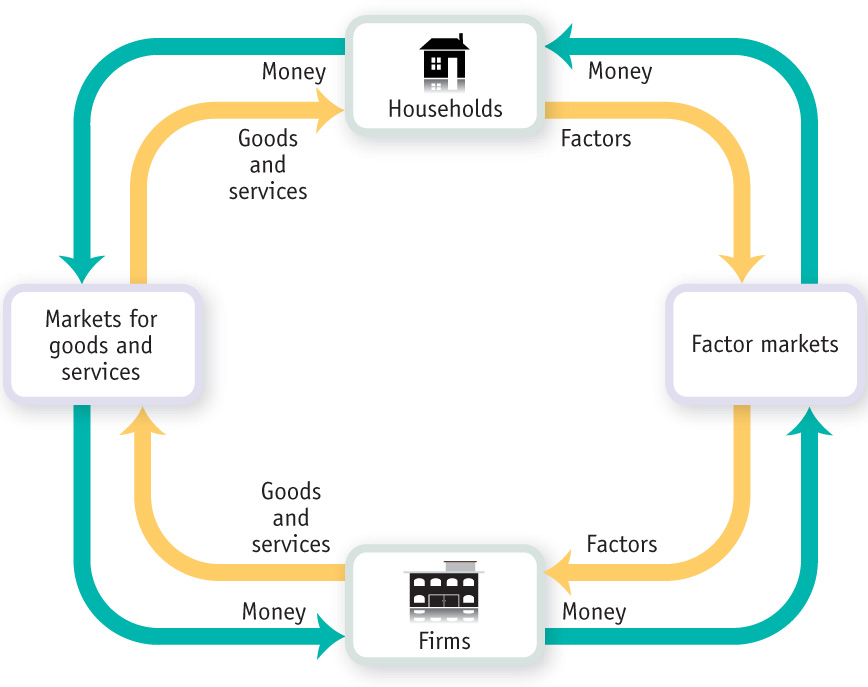

The U.S. economy is a vastly complex entity, with more than 155 million workers employed by more than 27 million companies, producing millions of different goods and services. Yet you can learn some very important things about the economy by considering the simple graphic shown in Figure 2-1. This circular-flow diagram is a simplified representation of the way money, goods and services, and factors of production flow through the economy. The yellow arrows show how goods, services, labor, and raw materials flow in one direction, and the bluish–green arrows show how the money that pays for these things flows in the opposite direction. The underlying principle is that the flow of money into each market or sector is equal to the flow of money coming out of that market or sector.

The circular-flow diagram represents the transactions in an economy by flows around a circle.

A household is a person or a group of people who share income.

A firm is an organization that produces goods and services for sale.

This simple model illustrates an economy that contains only two types of participants: households and firms. A household consists of either an individual or a group of people (typically a family) who share their income. A firm is an organization or business that produces goods or services for sale—and that employs members of households.

Product markets are where goods and services are bought and sold.

As shown in Figure 2-1, there are two kinds of markets in this simple economy. On the left side are markets for goods and services, also known as product markets, in which households buy the goods and services they want from firms. This produces a flow of goods and services to households and a return flow of money to firms.

Factor markets are where resources, especially capital and labor, are bought and sold.

On the right side are factor markets in which firms buy the resources they need to produce goods and services. Recall from the preceding module that the factors of production are land, labor, physical capital, and human capital.

The best known factor market is the labor market, in which workers are paid for their time and effort. Besides labor, we can think of households as owning the other factors of production as well, and selling them to firms. For example, when a corporation pays dividends to its stockholders, who are members of households, it is in effect paying them for the use of the machines and buildings that belong to those investors.

In the interest of simplicity, the circular-flow diagram in Figure 2-1 does not include a number of real-world complications. A few examples:

- In the real world, the distinction between firms and households isn’t always that clear-cut. Consider a small, family-run business—a farm, a shop, a small hotel. Is this a firm or a household? A more complete picture would include a separate box for family businesses.

- A more complete picture would include the flows of goods, services, and money within the business sector.

- A more complete picture would include the sale of goods by firms to other firms; for example, steel companies sell mainly to other companies such as auto manufacturers, not to households.

- The diagram doesn’t show the government, which takes money out of the circular flow in the form of taxes and injects it back into the flow as spending.

Figure 2-1, in other words, is by no means a complete picture of the economy’s participants and the flows that take place among them. But despite its simplicity, the circular-flow diagram is a useful guide to how the economy works and how the participants are interconnected. Next we’ll take a closer look at the relationship between individual decision making and broader economic outcomes.

One Person’s Spending Is Another Person’s Income

The circular-flow diagram shows that what goes around comes around. The circularity of spending magnifies the importance of individual and firm behavior at every level. And it helps to explain why reduced spending by one segment of the economy can lead to problems for almost everyone in the economy.

Consider Wichita, Kansas, known as the “Air Capital of the World” because so many airplanes are made there. In 2010, even as the economy recovered from the recession of 2007–2009, several corporations that had been buying a lot of airplanes decided to cut back on their purchases. These cuts bruised the Wichita economy, and spending dropped off at the city’s retail stores. A similar problem occurred at the national level in 2001 and 2008, when cuts in business investment spending fueled a sharp downfall in retail sales.

But why should cuts in spending on airplanes by businesses mean empty stores in the shopping malls? After all, malls are places where families, not businesses, go to shop. The answer is that lower business spending led to lower incomes throughout the economy, because people who had been making those airplanes lost their jobs or were forced to take pay cuts. Between 2008 and 2010, Wichita’s aviation industry lost about 13,000 jobs. As incomes evaporated in the aviation industry, so did spending by consumers who worked in the aviation industry. And then incomes and spending in industries supported by aviation workers—retail sales, day care, home construction, and so on—fell, and the domino effect of falling consumption and falling incomes continued.

If one group in the economy spends more, the income of other groups will rise.

© INSADCO Photography/Alamy

|

If one group spends less, the income of other groups will fall.

istockphoto/thinkstock

|

This story illustrates a general principle: One person’s spending is another person’s income. In a market economy, people make a living selling things—including their labor—to other people. If some group in the economy decides, for whatever reason, to spend more, the income of other groups will rise. If some group decides to spend less, the income of other groups will fall.

Because one person’s spending is another person’s income, a chain reaction of changes in spending behavior occurs. Spending cuts lead to reduced family incomes; families respond by reducing consumer spending, which leads to reductions in hiring by firms, and another round of income cuts; and so on.

Through these repercussions, individual and firm decisions send ripple effects throughout the economy. Keep in mind that behavior on the micro level can have macro consequences.

Module 2 Review

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

1. Use the circular-flow diagram to explain how an increase in the amount of money spent by households results in an increase in the number of jobs in the economy.

2. Oil companies are investing heavily in projects that will extract oil from the “oil sands” of Canada. Near these projects, in Edmonton, Alberta, restaurants and other consumer businesses are booming. Explain why on the basis of a principle you learned about in this module.

Multiple-Choice Questions

Question

6QreGVbfPMtNWd+nFVCoYzmEaCwLCyPi6ExxlXY7dfVQfF3a/igMAqYDREIGmTVTdrPcMZJYdMhzRWbCFdw17UtxabPTqk72PDvKBHXJjWdEIvet+r1yoK1NqgqrCOrt2Ovw3mepia+IynP8qXdTRmEn+sPTNkkFJyoKTqLNd6AqPj/bog527KxNxMJJMhziUA7gdg8eMqP6cRHLlRsF+GaILiqPGxQhsaz4k5gtF+yOlUjdCpozS7knS5Rb5qmO+mvM9OOKR4Qyqo4w6+Cyzzu4EzLt+Hh9ymC2EWzPhT5OEXyHqCGLvwH/UzIIPnRYiLcaF36iDl/HXe6CZCJKacg3itLhU+0Zx7Dz0WUhI/rE3yidIPU5gbqYzzY6iMhsSjZt9aYQDpamA6/kGMmDxayB1T9uSWA+0Ffe7Zj4D+eWtsoUlDtuqSAY8Z52KuH0FiWBSLY8G3w=Question

SHwlAIn1hrSj6fHV5Td2K/Jq2kDx5ds/zRLnb+BSVfLjH3HoitZDWjicu3NxjBcWqAnrjfUVQZxilJ82WbvIhz+EGZBNK41W41XaJVgMtq4i2YtutdlCTMhMpJhz7nD6J7JEo2577uPx2kq6BcKpMGumkqbIgkvtedJUI44xVpVoHx9Wq8HAwwokgV2mqVyEBDY9vzhWvcv+8+d6I+e3JierbbwnlhHUZ3nsGSAZ2Yiivjt+wYCUd82Hu9+/aPCpWCDLC3BqpDCm/pVxTSxluYhQJRcxE+NVWqste3P+xbGg3tpXpEXq+47b3t5wVmfXIqBHHaGlWT/+njzIwmxJCVNXCuhuR0T5KauOKg4KvjEwsv5CzDWyQ5XxHjC/TFkzKutQ7BuA5FaLy0GptEIQvC6fOadn7VlRu0EX7jykeXNjI2dOY8LzIoU5vL1idiFibrnqDEE4+PkBT0XReL6p9AAL4WJ1Q8cR3SC+1cguec9NdKGmcV2g4DLY+xPYDmFmpHWfUWDg670ph+A+r2utDLLXSVGot1QdQuestion

Spx+pUcBswPJHk3NgKI/lS/17sSI8wXrPTJLc2/Qhdf1nfjCbC0XSzcXfZZ3xErKscAyPgEeM6+xYllDlxe83PetHbmlG123crpwJ1L49UENam85rH6dZA94GxD5DqS+uY09ThmHVNDZ9Jezd3fwjnbB2mGRwv2TxTnefHytmw/Jyq6JlBKw3E0aKb6pIElDAboKEQR3kQLhFh3iARyHD/vkW8qmA5zoWgSgWrbyKdd96yYQmIVO+jXI0K/Z/ajmsELuCPfA0O3p0bO0pwmDV3GNkP6Hs88KAwEGxLlfMfvxMEphs9XmJzgfuDN+XVDwQuestion

v4ORGLDt5APKWnH64pBjSB9tiuexODKWuw+87Ydwq50NriqdudMiTcC8zW4ckdnasxetHQLfCBOpB2O1G8aXM0g6989o9X63MvIrgnQfH8aAAspQddyVp0Btv36EqMyBNpiilj+QLV2p/MuFalRV0QjHDgsLzwItjNNvNMWiHVK5ws/nOom+w5A0d2YWh1bobeJMW9vyguYFiElHkREhXKQ3G9yU/HuSD0CppGRBq+zUsEj6xbXXIsdH9/HjBoBvLUxtRvVmIfe+zIaYZdbUWlo9l8cYwU1225DifCdxacSRa67kiB9cQimsUXU=Question

g+kkG55K1Ijj9X1roxQG6fmqYsjwoyoSnLK5YUAhTMJkvuNkP9DjIuyTO0r3Ouxj6kMr5Qp+FSRaTOSeWiP4FdMZVj38mmlUYj0YsZocM5+8dzIFogVR86doEbCo5MuibMsJGU8kpfBdVrBQwV3uP36+kBfeZGuIItG9ARkETMtUyIRd1wvrnNj7DjJ97/I4ZYfkydgkkauFJ1B5inpIJgX/P1CxqQkN4Z3skjJwDRXP9bCR+bMcNtyw/4Q9ATTNMrqXbMcM1+U=Critical-Thinking Question

The inhabitants of the fictional economy of Atlantis use money in the form of cowry shells. Draw a circular-flow diagram showing households and firms. Firms produce potatoes and fish, and households buy potatoes and fish. Households also provide the land and labor to firms. Identify where, within the flows of cowry shells, goods and services, or resources, each of the following impacts would occur. Describe how this impact spreads around the circle.

- a. A devastating hurricane floods many of the potato fields.

- b. A productive fishing season yields an especially large number of fish.

- c. The inhabitants of Atlantis discover the music of singer Beyoncé and spend several days a month at dancing festivals.