1.1 Module 24: Introduction to Market Structure

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

The meaning and dimensions of market structure

The meaning and dimensions of market structure

The four principal types of market structure—

The four principal types of market structure—perfect competition, monopoly, oligopoly, and monopolistic competition

To discuss the supply curve in a market, we need to identify the type of market we are looking at. In this module we will learn about the basic characteristics of the four major types of markets in the economy.

Types of Market Structure

The real world holds a mind-

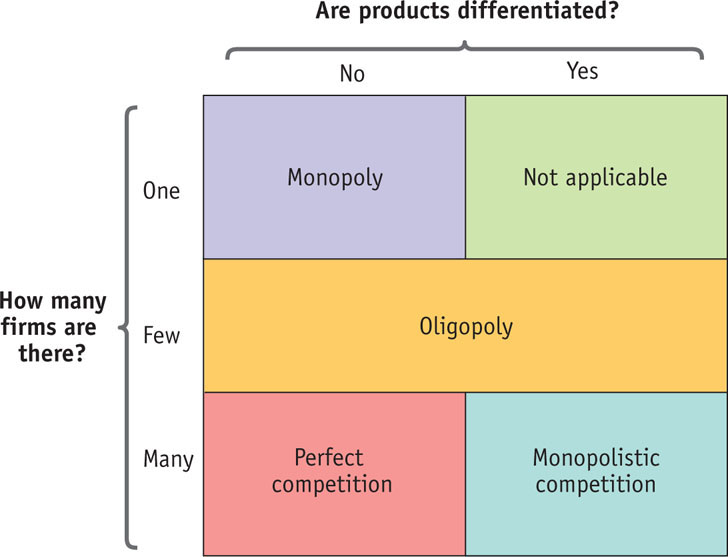

In order to develop principles and make predictions about markets and firm behavior, economists have developed four primary models of market structure: perfect competition, monopoly, oligopoly, and monopolistic competition. This system of market structure is based on two dimensions:

- the number of firms in the market (one, few, or many)

- whether the goods offered are identical or differentiated.

Differentiated goods are goods that are different but considered at least somewhat substitutable by consumers—

Figure 24-1 provides a simple visual summary of the types of market structure classified according to the two dimensions. In perfect competition many firms each sell an identical product. In monopoly, a single firm sells a single, undifferentiated product. In oligopoly, a few firms—

Perfect Competition

Suppose that Yves and Zoe are neighboring farmers, both of whom grow organic tomatoes. Both sell their output to the same grocery store chains that carry organic foods; so, in a real sense, Yves and Zoe compete with each other.

Does this mean that Yves should try to stop Zoe from growing tomatoes or that Yves and Zoe should form an agreement to grow fewer? Almost certainly not: there are hundreds or thousands of organic tomato farmers, and Yves and Zoe are competing with all those other growers as well as with each other. Because so many farmers sell organic tomatoes, if any one of them produced more or fewer, there would be no measurable effect on market prices.

When people talk about business competition, they often imagine a situation in which two or three rival firms are struggling for advantage. But economists know that when a business focuses on a few main competitors, it’s actually a sign that competition is fairly limited. As the example of organic tomatoes suggests, when the number of competitors is large, it doesn’t even make sense to identify rivals and engage in aggressive competition because each firm is too small within the scope of the market to make a significant difference.

The actions of a price-

A price-

We can put it another way: Yves and Zoe are price-

Defining Perfect Competition

A perfectly competitive market is a market in which all market participants are price-

In a perfectly competitive market, all market participants, both consumers and producers, are price-

The supply and demand model is a model of a perfectly competitive market. It depends fundamentally on the assumption that no individual buyer or seller of a good, such as raw cotton or organic tomatoes, believes that it is possible to individually affect the price at which he or she can buy or sell the good. For a firm, being a price-

A perfectly competitive industry is an industry in which firms are price-

As a general rule, consumers are indeed price-

Under what circumstances will all firms be price-

Two Necessary Conditions for Perfect Competition

The markets for major grains, such as wheat and corn, are perfectly competitive: individual wheat and corn farmers, as well as individual buyers of wheat and corn, take market prices as given. In contrast, the markets for some of the food items made from these grains—

A firm’s market share is the fraction of the total industry output accounted for by that firm’s output.

1. An Industry Must Contain Many Firms, Each Having a Small Market ShareFor an industry to be perfectly competitive, it must contain many firms, none of whom have a large market share. A firm’s market share is the fraction of the total industry output accounted for by that firm’s output.

The distribution of market share constitutes a major difference between the grain industry and the breakfast cereal industry. There are thousands of wheat farmers, none of whom account for more than a tiny fraction of total wheat sales. The breakfast cereal industry, however, is dominated by four firms: Kellogg’s, General Mills, Post, and Quaker Foods. Kellogg’s alone accounts for about one-

2. The Industry Must Produce a Standardized ProductAn industry can be perfectly competitive only if consumers regard the products of all firms as equivalent. This clearly isn’t true in the breakfast cereal market: consumers don’t consider Cap’n Crunch to be a good substitute for Shredded Wheat. As a result, the maker of Shredded Wheat has some ability to increase its price without fear that it will lose all its customers to the maker of Cap’n Crunch.

A good is a standardized product, also known as a commodity, when consumers regard the products of different firms as the same good.

Contrast this with the case of a standardized product, sometimes known as a commodity, which is a product that consumers regard as the same good even when it comes from different firms. Because wheat is a standardized product, consumers regard the output of one wheat producer as a perfect substitute for that of another producer. Consequently, one farmer cannot increase the price for his or her wheat without losing all sales to other wheat farmers. So the second necessary condition for a perfectly competitive industry is that the industry output is a standardized product. (See the upcoming Economics in Action.)

!world_eia!WHAT’S A STANDARDIZED PRODUCT?

A perfectly competitive industry must produce a standardized product. But is it enough for the products of different firms actually to be the same? No: people must also think that they are the same. And producers often go to great lengths to convince consumers that they have a distinctive, or differentiated, product, even when they don’t.

Consider, for example, champagne—

Similarly, Korean producers of kimchi, the spicy fermented cabbage that is the Korean national side dish, are doing their best to convince consumers that the same product packaged by Japanese firms is just not the real thing. The purpose is, of course, to ensure higher prices for Korean kimchi.

So is an industry perfectly competitive if it sells products that are indistinguishable except in name but that consumers, for whatever reason, don’t think are standardized? No. When it comes to defining the nature of competition, the consumer is always right.

Free Entry and Exit

An industry has free entry and exit when new firms can easily enter into the industry and existing firms can easily leave the industry.

Most perfectly competitive industries are also characterized by one more feature: it is easy for new firms to enter the industry or for firms that are currently in the industry to leave. That is, no obstacles in the form of government regulations or limited access to key resources prevent new firms from entering the market. And no additional costs are associated with shutting down a company and leaving the industry. Economists refer to the arrival of new firms into an industry as entry; they refer to the departure of firms from an industry as exit. When there are no obstacles to entry into or exit from an industry, we say that the industry has free entry and exit.

Free entry and exit is not strictly necessary for perfect competition. However, it ensures that the number of firms in an industry can adjust to changing market conditions. And, in particular, it ensures that firms in an industry cannot act to keep other firms out.

To sum up, then, perfect competition depends on two necessary conditions. First, the industry must contain many firms, each having a small market share. Second, the industry must produce a standardized product. In addition, perfectly competitive industries are normally characterized by free entry and exit.

Monopoly

The De Beers diamond monopoly of South Africa was created in the 1880s by Cecil Rhodes, a British businessman. By 1880, mines in South Africa already dominated the world’s supply of diamonds. There were, however, many mining companies, all competing with each other. During the 1880s Rhodes bought the great majority of those mines and consolidated them into a single company, De Beers. By 1889, De Beers controlled almost all of the world’s diamond production.

De Beers, in other words, became a monopolist. But what does it mean to be a monopolist? And what do monopolists do?

Defining Monopoly

As we mentioned earlier, the supply and demand model of a market is not universally valid. Instead, it’s a model of perfect competition, which is only one of several types of market structure. A market will be perfectly competitive only if there are many firms, all of which produce the same good. Monopoly is the most extreme departure from perfect competition.

A monopolist is the only producer of a good that has no close substitutes. An industry controlled by a monopolist is known as a monopoly.

A monopolist is a firm that is the only producer of a good that has no close substitutes. An industry controlled by a monopolist is known as a monopoly.

In practice, true monopolies are hard to find in the modern American economy, partly because of legal obstacles. A contemporary entrepreneur who tried to consolidate all the firms in an industry the way Rhodes did would soon find himself in court, accused of breaking antitrust laws, which are intended to prevent monopolies from emerging. Monopolies do, however, play an important role in some sectors of the economy.

Why Do Monopolies Exist?

A monopolist making profits will not go unnoticed by others. (Recall that we mean “economic profit,” revenue over and above the opportunity costs of the firm’s resources.) But won’t other firms crash the party, grab a piece of the action, and drive down prices and profits in the long run?

To earn economic profits, a monopolist must be protected by a barrier to entry—something that prevents other firms from entering the industry.

If possible, yes, they will. For a profitable monopoly to persist, something must keep others from going into the same business; that “something” is known as a barrier to entry. There are four principal types of barriers to entry: control of a scarce resource or input, economies of scale, technological superiority, and government-

Control of a Scarce Resource or InputA monopolist that controls a resource or input crucial to an industry can prevent other firms from entering its market. Cecil Rhodes made De Beers into a monopolist by establishing control over the mines that produced the bulk of the world’s diamonds.

Economies of ScaleMany Americans have natural gas piped into their homes for cooking and heating. Invariably, the local gas company is a monopolist. But why don’t rival companies compete to provide gas?

In the early nineteenth century, when the gas industry was just starting up, companies did compete for local customers. But this competition didn’t last long; soon local gas companies became monopolists in almost every town because of the large fixed cost of providing a town with gas lines. The cost of laying gas lines didn’t depend on how much gas a company sold, so a firm with a larger volume of sales had a cost advantage: because it was able to spread the fixed cost over a larger volume, it had a lower average total cost than smaller firms.

The natural gas industry is one in which average total cost falls as output increases, resulting in economies of scale and encouraging firms to grow larger. In an industry characterized by economies of scale, larger firms are more profitable and drive out smaller ones. For the same reason, established firms have a cost advantage over any potential entrant—

A natural monopoly exists when economies of scale provide a large cost advantage to a single firm that produces all of an industry’s output.

A monopoly created and sustained by economies of scale is called a natural monopoly. The defining characteristic of a natural monopoly is that it possesses economies of scale over the range of output that is relevant for the industry. The source of this condition is large fixed costs: when large fixed costs are required to operate, a given quantity of output is produced at lower average total cost by one large firm than by two or more smaller firms.

The most visible natural monopolies in the modern economy are local utilities—

Technological SuperiorityA firm that maintains a consistent technological advantage over potential competitors can establish itself as a monopolist. For example, from the 1970s through the 1990s, the chip manufacturer Intel was able to maintain a consistent advantage over potential competitors in both the design and production of microprocessors, the chips that run computers. But technological superiority is typically not a barrier to entry over the longer term: over time competitors will invest in upgrading their technology to match that of the technology leader. In fact, in the last few years Intel found its technological superiority eroded by a competitor, Advanced Micro Devices (also known as AMD), which was able to produce chips approximately as fast and as powerful as Intel chips.

We should note, however, that in certain high-

Government-

A patent gives an inventor a temporary monopoly in the use or sale of an invention.

A copyright gives the creator of a literary or artistic work the sole right to profit from that work.

The most important legally created monopolies today arise from patents and copyrights. A patent gives an inventor the sole right to make, use, or sell that invention for a period that in most countries lasts between 16 and 20 years. Patents are given to the creators of new products, such as drugs or mechanical devices. Similarly, a copyright gives the creator of a literary or artistic work the sole right to profit from that work, usually for a period equal to the creator’s lifetime plus 70 years.

The justification for patents and copyrights is a matter of incentives. If inventors were not protected by patents, they would gain little reward from their efforts: as soon as a valuable invention was made public, others would copy it and sell products based on it. And if inventors could not expect to profit from their inventions, then there would be no incentive to incur the costs of invention in the first place. Likewise for the creators of literary or artistic works. So the law allows a monopoly to exist temporarily by granting property rights that encourage invention and creation.

Patents and copyrights are temporary because the law strikes a compromise. The higher price for the good that holds while the legal protection is in effect compensates inventors for the cost of invention; conversely, the lower price that results once the legal protection lapses benefits consumers.

Because the lifetime of the temporary monopoly cannot be tailored to specific cases, this system is imperfect and leads to some missed opportunities. In some cases there can be significant welfare issues. For example, the violation of American drug patents by pharmaceutical companies in poor countries has been a major source of controversy, pitting the needs of poor patients who cannot afford to pay retail drug prices against the interests of drug manufacturers who have incurred high research costs to discover these drugs. To solve this problem, some American drug companies and poor countries have negotiated deals in which the patents are honored but the American companies sell their drugs at deeply discounted prices. (This is an example of price discrimination, which we’ll learn more about in the next section.)

Oligopoly

An oligopoly is an industry with only a small number of firms. A producer in such an industry is known as an oligopolist.

An industry with only a few firms is known as an oligopoly; a producer in such an industry is known as an oligopolist.

Oligopolists compete with each other for sales. But oligopolists aren’t like producers in a perfectly competitive industry, who take the market as given. Oligopolists know their decisions about how much to produce will affect the market price. That is, like monopolists, oligopolists have some market power.

When no one firm has a monopoly, but producers nonetheless realize that they can affect market prices, an industry is characterized by imperfect competition.

Economists refer to a situation in which firms compete but also possess market power—

Many familiar goods and services are supplied by only a few competing sellers, which means the industries in question are oligopolies. For example, most air routes are served by only two or three airlines: in recent years, regularly scheduled shuttle service between New York and either Boston or Washington, D.C., has been provided only by Delta and US Airways. Three firms—

It’s important to realize that an oligopoly isn’t necessarily made up of large firms. What matters isn’t size per se; the question is how many competitors there are. When a small town has only two grocery stores, grocery service there is just as much an oligopoly as air shuttle service between New York and Washington.

Why are oligopolies so prevalent? Essentially, an oligopoly is the result of the same factors that sometimes produce a monopoly, but in somewhat weaker form. Probably the most important source of oligopolies is the existence of economies of scale, which give bigger firms a cost advantage over smaller ones. When these effects are very strong, as we have seen, they lead to a monopoly; when they are not that strong, they lead to an industry with a small number of firms. For example, larger grocery stores typically have lower costs than smaller stores. But the advantages of large scale taper off once grocery stores are reasonably large, which is why two or three stores often survive in small towns.

Is It an Oligopoly or Not?

In practice, it is not always easy to determine an industry’s market structure just by looking at the number of sellers. Many oligopolistic industries contain a number of small “niche” firms, which don’t really compete with the major players. For example, the U.S. airline industry includes a number of regional airlines such as New Mexico Airlines, which flies propeller planes between Albuquerque and Carlsbad, New Mexico; if you count these carriers, the U.S. airline industry contains nearly one hundred firms, which doesn’t sound like competition among a small group. But there are only a handful of national competitors like American and United, and on many routes, as we’ve seen, there are only two or three competitors.

To get a better picture of market structure, economists often use a measure called the Herfindahl–

Herfindahl—

HHI = 602 + 252 + 152 = 4,450

By squaring each market share, the HHI calculation produces numbers that are much larger when a larger share of an industry output is dominated by fewer firms. So it’s a better measure of just how concentrated the industry is. This is confirmed by the data in Table 24-1. Here, the indices for industries dominated by a small number of firms, like the personal computer operating systems industry or the wide-

| Industry | HHI | Largest firms |

|---|---|---|

| PC operating systems | 9,182 | Microsoft, Linux |

| Wide- |

5,098 | Boeing, Airbus |

| Diamond mining | 2,338 | De Beers, Alrosa, Rio Tinto |

| Automobiles | 1,432 | GM, Ford, Chrysler, Toyota, Honda, Nissan, VW |

| Movie distributors | 1,096 | Buena Vista, Sony Pictures, 20th Century Fox, Warner Bros., Universal, Paramount, Lionsgate |

| Internet service providers | 750 | SBC, Comcast, AOL, Verizon, Road Runner, Earthlink, Charter, Qwest |

| Retail grocers | 321 | Walmart, Kroger, Sears, Target, Costco, Walgreens, Ahold, Albertsons |

|

Sources: Canadian Government; Diamond Facts 2006; www.w3counter.com; Planet retail; Autodata; Reuters; ISP Planet; Swivel. Data cover 2006– |

||

Monopolistic Competition

Leo manages the Wonderful Wok stand in the food court of a big shopping mall. He offers the only Chinese food there, but there are more than a dozen alternatives, from Bodacious Burgers to Pizza Paradise. When deciding what to charge for a meal, Leo knows that he must take those alternatives into account: even people who normally prefer stir-

But Leo also knows that he won’t lose all his business even if his lunches cost a bit more than the alternatives. Chinese food isn’t the same thing as burgers or pizza. Some people will really be in the mood for Chinese that day, and they will buy from Leo even if they could have dined more cheaply on burgers. Of course, the reverse is also true: even if Chinese is a bit cheaper, some people will choose burgers instead. In other words, Leo does have some market power: he has some ability to set his own price.

So how would you describe Leo’s situation? He definitely isn’t a price-

Yet it would also be wrong to call him an oligopolist. Oligopoly, remember, involves competition among a small number of interdependent firms in an industry protected by some—

Defining Monopolistic Competition

Economists describe Leo’s situation as one of monopolistic competition. Monopolistic competition is particularly common in service industries such as the restaurant and gas station industries, but it also exists in some manufacturing industries. It involves three conditions:

- a large number of competing firms,

- differentiated products, and

- free entry into and exit from the industry in the long run.

Monopolistic competition is a market structure in which there are many competing firms in an industry, each firm sells a differentiated product, and there is free entry into and exit from the industry in the long run.

In a monopolistically competitive industry, each producer has some ability to set the price of her differentiated product. But exactly how high she can set it is limited by the competition she faces from other existing and potential firms that produce close, but not identical, products.

Large NumbersIn a monopolistically competitive industry there are many firms. Such an industry does not look either like a monopoly, where the firm faces no competition, or like an oligopoly, where each firm has only a few rivals. Instead, each seller has many competitors. For example, there are many vendors in a big food court, many gas stations along a major highway, and many hotels at a popular beach resort.

Differentiated ProductsIn a monopolistically competitive industry, each firm has a product that consumers view as somewhat distinct from the products of competing firms. Such product differentiation can come in the form of different styles or types, different locations, or different levels of quality. At the same time, though, consumers see these competing products as close substitutes. If Leo’s food court contained 15 vendors selling exactly the same kind and quality of food, there would be perfect competition: any seller who tried to charge a higher price would have no customers. But suppose that Wonderful Wok is the only Chinese food vendor, Bodacious Burgers is the only hamburger stand, and so on. The result of this differentiation is that each vendor has some ability to set his or her own price: each firm has some—

Free Entry and Exit in the Long RunIn monopolistically competitive industries, new firms, with their own distinct products, can enter the industry freely in the long run. For example, other food vendors would open outlets in the food court if they thought it would be profitable to do so. In addition, firms will exit the industry if they find they are not covering their costs in the long run.

Monopolistic competition, then, differs from the three market structures we have examined so far. It’s not the same as perfect competition: firms have some power to set prices. It’s not pure monopoly: firms face some competition. And it’s not the same as oligopoly: there are many firms and free entry, which eliminates the potential for collusion that is so important in oligopoly. As we’ll see in a later section, competition among the sellers of differentiated products is the key to understanding how monopolistic competition works.

Now that we have introduced the idea of market structure and presented the four principal models of market structure, we can proceed to explain and predict firm behavior (e.g., price and quantity determination) and analyze individual markets.

Module 24 Review

Check Your Understanding

1. In each of the following situations, what type of market structure do you think the industry represents?

-

a. There are three producers of aluminum in the world, a good sold in many places.

-

b. There are thousands of farms that produce indistinguishable soybeans to thousands of buyers.

-

c. Many designers sell high-

fashion clothes. Each designer has a distinctive style and a somewhat loyal clientele. -

d. A small town in the middle of Alaska has one bicycle shop.

Multiple-

Question

JU6pJMxQbM6JWTPDzKk5/V1rNdAex8ab2JzSTBeFiOzl3iKqk7gz7NCu3ngXLpKoog6p6+m1DinV1W223b5/9rOSe6q6WVTt19c/ddkfooQEmursq3RzDSpJ0K8rya6AhhKGn86r4fT+D/kULrAiz/uQp8sDcnN1+ug5GYIB++rHCsEJFOk0F89BBuHOGkey3V5c0VIs4LZiaSOxF8fKT+KCz7tBtQNSh2Yge3OtEq2DIOaqakWMoEu00+9/9Vc/nE8Z8kzIIzztZBgYEfj5IrG0ybJ/QXgaqisn98/V0l/9Q/6gnpv6rMtaFhfhkmuN+264CEzthdMQa2HOWrlIujItAQcB41WGcCX+DIp76l2npsZ1Wv5tjjelN613gnraU5SqpkBdD5pUjEE3C59lUVphoFxZBbfmVNuADLadPZF0l+bz1tgupMfD0oXgsOUAh/9vsz3eUGzkP0cQ2jBrBK8MVNhc37bcnf/8bDqn5IGg99NS0B7pvU345jFuq/EWEJuEvAE/uQj8yi9T28l6vJ4fdzLEbdlSRhYiLMyrTwngJGR6mWpd+NiM8MEpk786MHuui0+i9eY=Question

Vld4tVD83wVqDqz35UmHXBFSdvC0ESrILW8B/BW83EpVRzdW5qysrIQua/07n1Q/ebIIBSpX3KHwoFUPW/B50YFGYh7FHUXDfPbFL+Ld45mV393h/udG37i1MwnyMmY7cnRlRr7s+sa8aHhjUUaER1qpyF0lT7QVj93EbA81YN3fHFSjEDeKrW/DbyTyCfpaUwBVf7tMH2B9FFcC+qjihFDM1Zbc+adw5uNs62Mgl/XMIMSdepyD0dg993WqQJpf/6+SWRn2Kw57oQGaWStUCF4rW+J1Yr2j8a2kdKG20D6sKVjYgkE6XiMW99Zu2RQyFVpJBI4azk2ntL13QHN7JQlha5WCh8MH+0fjNKhsPjTecxDmECODXlaF5OiLOePKycopJSws3lVBal9cvQM8twy12z0MV6MVQUVGORYG8/OZCGnKN3vLRlXjsCRug9LngBaUQnAEugbraRru1Q1D7ZUnuA23D5rA8TnLKNugOwnSac5pll5FOOAgvAEAkDc3Question

4JMTRJyQBF3CcAWPJD7HH2XJMI/+YFYFGTSM4Ag+akpDHayNoMZL8qXNp6928YZa0XFhL14Go4UjlswDv2ygLvxzQy2cYZRaLN2C8KauNjbomvVltlB52S96xhQ6rjZEXTjE9iAUvrdnGwekgOM6248RSKXzPxLJK//5B07kXxAdr3FpAd7OrfcT0FSrvglJKEaIc+hlQSlPjwPay+rk//vW13n4rfaxXKl4Cghl9/Br0UkBqskbtyq79+wMP338WxfOtiBQbhSUVJZSEBSYVzTwAPrPiIBRI3C9aL2bBqV5vtIznHNPfdcRVxRgUkSdelBsnDfVwaMIEBYbLDFOLN3RRDDau/WPPC7SFVLaeVBYCUqATnQmzfYVyDdon0LIRgVqFFr4mZsGbocBe9AgpWwd9JjIaW0P2secRA5W5DY5B7A34qpYMZ5u5FjZSe9fI68fhOt612CuLtd0HXD6cZfA2ccoE/JvTce9eNePUsSoavL8mO6ywkiCmqWBXMyJ9i1JOEV9MUertgvbw8Rff940y6xLsi3HLj/afMLN5ME=Question

kV+AJeY0J/SavqrNlidD8caqazlbxnCbJPc8qF8Pv0dqbzzUJJx/pQ+U6AbMAG3msFz0K61ixwPFSONgyk8nxW4s+6ljcbitGmcjBv7fTY6Tl4Kk0vh68xyBjfSCWw8oUAXELUcwdEtL6aWr+VuInhPLJ/AE/aUPyV+Y9NurZfHPvKZLfsOkld5RH/9OX3fRHJkGijeht/V0NNphjhrRpZQZb32BP+s8TYBI3ogbLT4Hli5xyhc1RMy4khlAS6F0BKgAboxfiW/W06MwAeoJbWsZLoZfWAgY1fjLW6vyMT+0oj6DI9LHadisVCP5X7lZmWoSqJu6CoEnd+9GibJnSepMOc5ZB+0tB19Rq4iYvHjrjHrLuD9kHQ3Ioltl8aLGmBAvAU/amwV1xKZO6EMRTuzKysWymqbaTxCOyaCDNcPeKaNKmbkzypwCVS33r9AuEsrj0Gt4oMPmbLbMTVIBskBzBNI/9SSgX7Rqe6iz9/y1lcaK4EvmPYmpjnOrZwQPvDdk05CJg1MwvYojJpxs7ROCDAZtEAjP9ZHyOkE7lK9YEidOTkgfpRuWgiDWuOY4BS+8K4JTIColPL3wOdRND9WUjCBr+CIEEYlQB6uwZtDboThJR44sH1kJ5lToF9lTQuestion

5qVgDK95tr7CBdF+9bmiNN1Bf6w4ZpEgFQ8Kv+OKivc0b3xgjRKTZSnPXW1WSSsDac9GyYpsK015G+1hBbxbx0BC09rXQBheAXQhVTxwTC8bL/o72MOfeFKF9zCMnyNelDHNohV/Pxs9F+L1REv7r5HJAyXtggM5toXsWbof+/GgdSyd+IpbsDnN8RTeCE3eHekRszeeGEgZGyE9CZ5yhk3HPj6/di/l717Xt+Z2km928A3cqH9IeHHGKAJN9VqmjRKTVOVdwys5LLNtqF5KPA9sJHtuAmpXgUQnTPzOHKIzYqB+NiMGmuYDqoG1SG3wd2yNMyapxbY=Critical-

1. Draw a correctly labeled graph of a perfectly competitive firm’s demand curve if the market price is $10.

2. What does the firm’s marginal revenue equal any time it sells one more unit of its output?