Monopoly: The General Picture

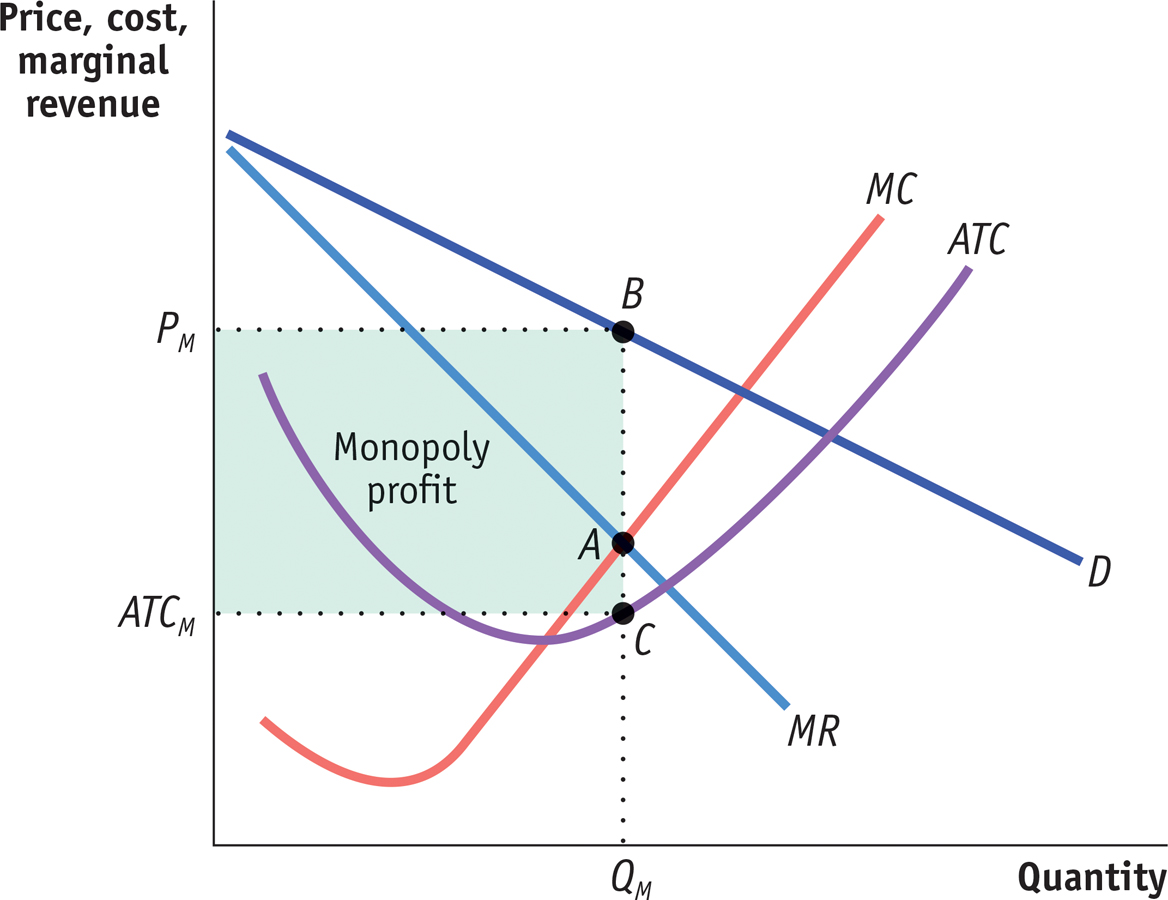

Figure 13-6 involved specific numbers and assumed that marginal cost was constant, that there was no fixed cost, and, therefore, that the average total cost curve was a horizontal line. Figure 13-7 shows a more general picture of monopoly in action: D is the market demand curve; MR, the marginal revenue curve; MC, the marginal cost curve; and ATC, the average total cost curve. Here we return to the usual assumption that the marginal cost curve has a “swoosh” shape and the average total cost curve is ∪-shaped.

Applying the optimal output rule, we see that the profit-

Recalling how we calculated profit in Equation 12-

Profit is equal to the area of the shaded rectangle in Figure 13-7, with a height of PM − ATCM and a width of QM.

In Chapter 12 we learned that a perfectly competitive industry can have profits in the short run but not in the long run. In the short run, price can exceed average total cost, allowing a perfectly competitive firm to make a profit. But we also know that this cannot persist.

In the long run, any profit in a perfectly competitive industry will be competed away as new firms enter the market. In contrast, barriers to entry allow a monopolist to make profits in both the short run and the long run.

ECONOMICS in Action: Shocked by the High Price of Electricity

Shocked by the High Price of Electricity

Historically, electric utilities were recognized as natural monopolies. A utility serviced a defined geographical area, owning the plants that generated electricity as well as the transmission lines that delivered it to retail customers. The rates charged customers were regulated by the government, set at a level to cover the utility’s cost of operation plus a modest return on capital to its shareholders.

Beginning in the late 1990s, however, there was a move toward deregulation, based on the belief that competition would result in lower retail electricity prices Competition was introduced at two junctures in the channel from power generation to retail customers: (1) distributors would compete to sell electricity to retail customers, and (2) power generators would compete to supply power to the distributors.

That was the theory, at least. By 2014, only 16 states had instituted some form of electricity deregulation, while 7 had started but then suspended deregulation, leaving 27 states to continue with a regulated monopoly electricity provider. Why did so few states actually follow through on electricity deregulation?

One major obstacle to lowering electricity prices through deregulation is the lack of choice in power generators, the bulk of which still entail large up-

In fact, deregulation can make consumers worse off when there is only one power generator. That’s because deregulation allows the power generator to engage in market manipulation—

Another problem is that without prices set by regulators, producers aren’t guaranteed a profitable rate of return on new power plants. As a result, in states with deregulation, capacity has failed to keep up with growing demand. For example, Texas, a deregulated state, has experienced massive blackouts due to insufficient capacity, and in New Jersey and Maryland, regulators have intervened to compel producers to build more power plants.

Lastly, consumers in deregulated states have been subject to big spikes in their electricity bills, often paying much more than consumers in regulated states. So, angry customers and exasperated regulators have prompted many states to shift into reverse, with Illinois, Montana, and Virginia moving to regulate their industries. California and Montana have gone so far as to mandate that their electricity distributors reacquire power plants that were sold off during deregulation. In addition, regulators have been on the prowl, fining utilities in Texas, New York, and Illinois for market manipulation.

Quick Review

The crucial difference between a firm with market power, such as a monopolist, and a firm in a perfectly competitive industry is that perfectly competitive firms are price-

takers that face horizontal demand curves, but a firm with market power faces a downward- sloping demand curve. Due to the price effect of an increase in output, the marginal revenue curve of a firm with market power always lies below its demand curve. So a profit-

maximizing monopolist chooses the output level at which marginal cost is equal to marginal revenue— not to price. As a result, the monopolist produces less and sells its output at a higher price than a perfectly competitive industry would. It earns profits in the short run and the long run.

13-2

Question 13.4

Use the accompanying total revenue schedule of Emerald, Inc., a monopoly producer of 10-

carat emeralds, to calculate the answers to parts a– d. Then answer part e. Quantity of emeralds demanded

Total revenue

1

$100

2

186

3

252

4

280

5

250

The demand schedule

The marginal revenue schedule

The quantity effect component of marginal revenue per output level

The price effect component of marginal revenue per output level

What additional information is needed to determine Emerald, Inc.’s profit-

maximizing output?

Question 13.5

Use Figure 13-6 to show what happens to the following when the marginal cost of diamond production rises from $200 to $400.

Marginal cost curve

Profit-

maximizing price and quantity Profit of the monopolist

Perfectly competitive industry profits

Solutions appear at back of book.