The Legal Framework

To understand oligopoly pricing in practice, we must be familiar with the legal constraints under which oligopolistic firms operate. In the United States, oligopoly first became an issue during the second half of the nineteenth century, when the growth of railroads—

Large firms producing oil, steel, and many other products soon emerged. The industrialists quickly realized that profits would be higher if they could limit price competition. So, many industries formed cartels—

However, although these cartels were legal, they weren’t legally enforceable—

In 1881 clever lawyers at John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company came up with a solution—

Contrasting Approaches to Antitrust Regulation

In the European Union, a competition commission enforces competition and antitrust regulation for the 28 member nations. The commission has the authority to block mergers, force companies to sell subsidiaries, and impose heavy fines if it determines that companies have acted unfairly to inhibit competition.

Although companies are able to dispute charges at a hearing once a complaint has been issued, if the commission feels that its own case is convincing, it rules against the firm and levies a penalty. Companies that believe they have been unfairly treated have only limited recourse. Critics complain that the commission acts as prosecutor, judge, and jury.

In contrast, charges of unfair competition in the United States must be made in court, where lawyers for the Federal Trade Commission have to present their evidence to independent judges. Companies employ legions of highly trained and highly paid lawyers to counter the government’s case. For U.S. regulators, there is no guarantee of success. In fact, judges in many cases have found in favor of companies and against the regulators. Moreover, companies can appeal unfavorable decisions, so reaching a final verdict can take several years.

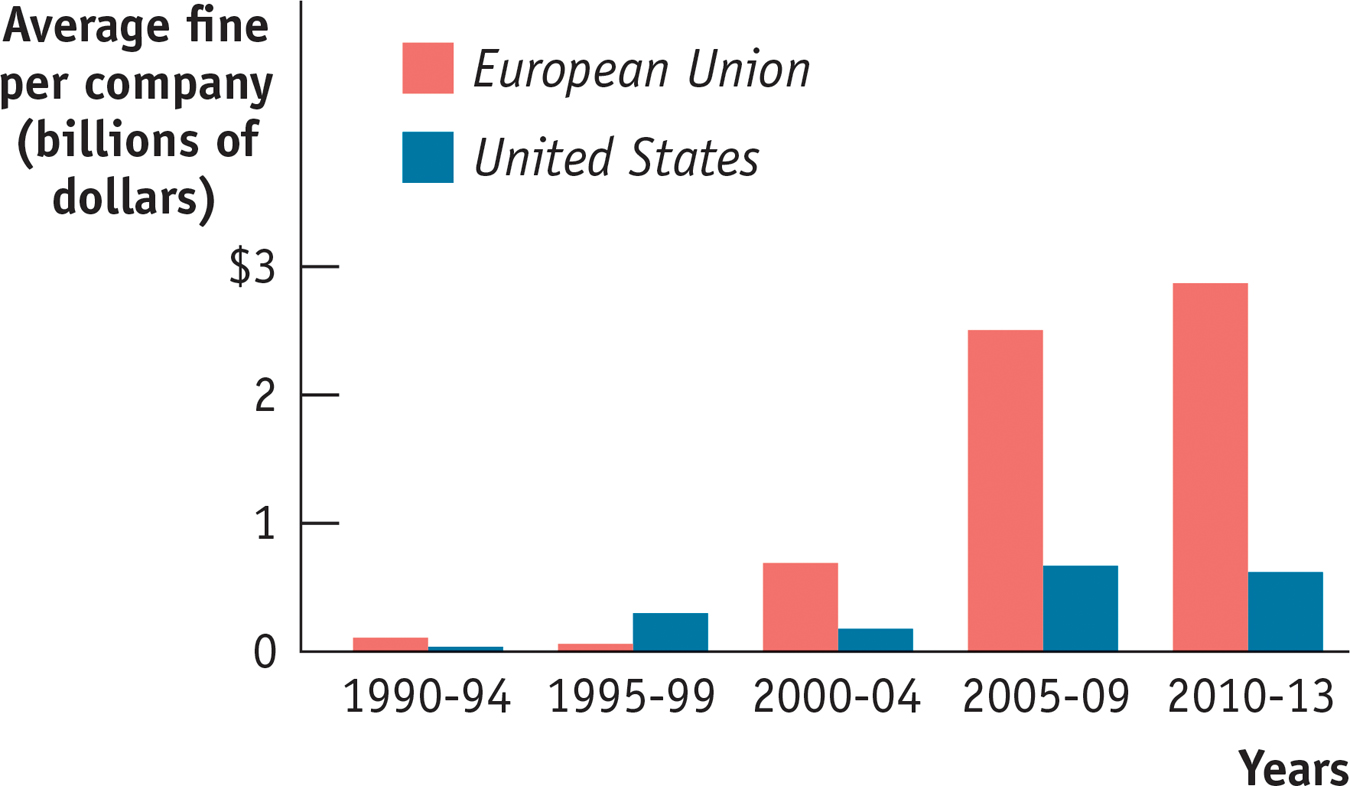

Companies, not surprisingly, prefer the American system. The accompanying figure further shows why. In recent years, on average, fines for unfair competition have been higher in the European Union than in the United States.

Observers, however, criticize both systems for their inadequacies. In the slow-

Sources: European Commission, Department of Justice Workload Statistics; PACIFIC Exchange Rate Service at University of British Columbia.

Antitrust policy consists of efforts undertaken by the government to prevent oligopolistic industries from becoming or behaving like monopolies.

Eventually there was a public backlash, driven partly by concern about the economic effects of the trust movement, partly by fear that the owners of the trusts were simply becoming too powerful. The result was the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which was intended both to prevent the creation of more monopolies and to break up existing ones. At first this law went largely unenforced. But over the decades that followed, the federal government became increasingly committed to making it difficult for oligopolistic industries either to become monopolies or to behave like them. Such efforts are known to this day as antitrust policy.

One of the most striking early actions of antitrust policy was the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911. (Its components formed the nuclei of many of today’s large oil companies—

Among advanced countries, the United States is unique in its long tradition of antitrust policy. Until recently, other advanced countries did not have policies against price-

During the early 1990s, the United States instituted an amnesty program in which a price-

Life has gotten much tougher over the past few years if you want to operate a cartel. So what’s an oligopolist to do?