Price, Marginal Cost, and Average Total Cost

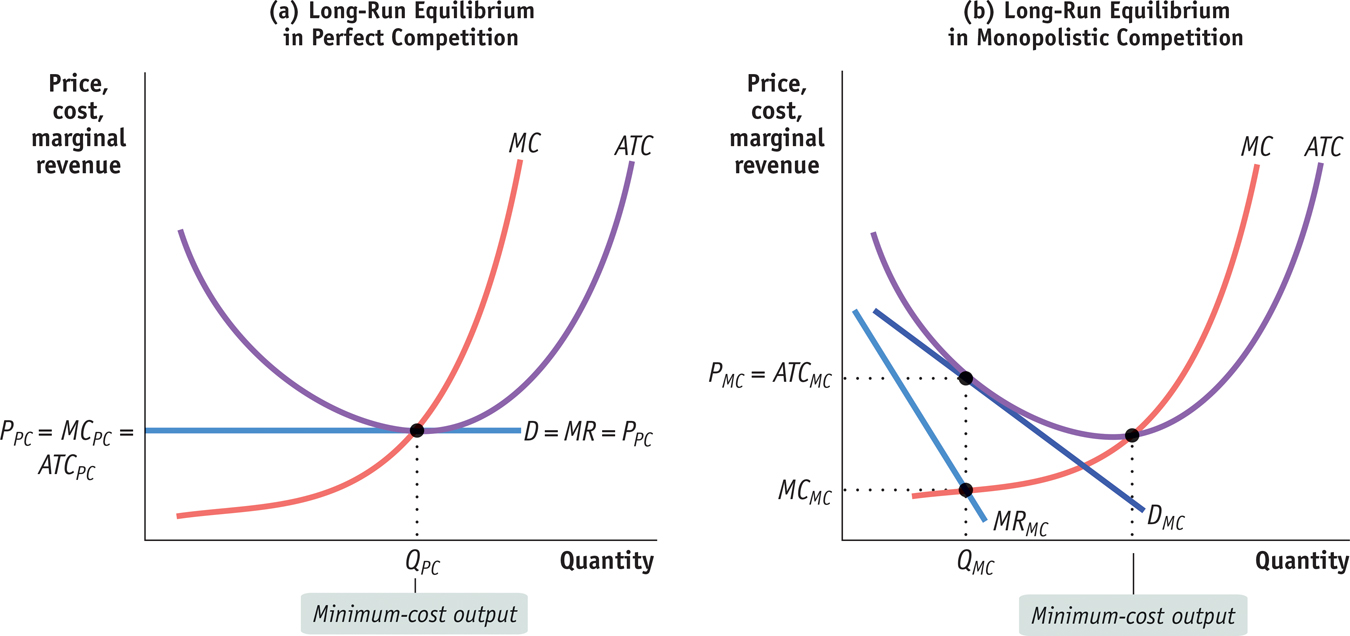

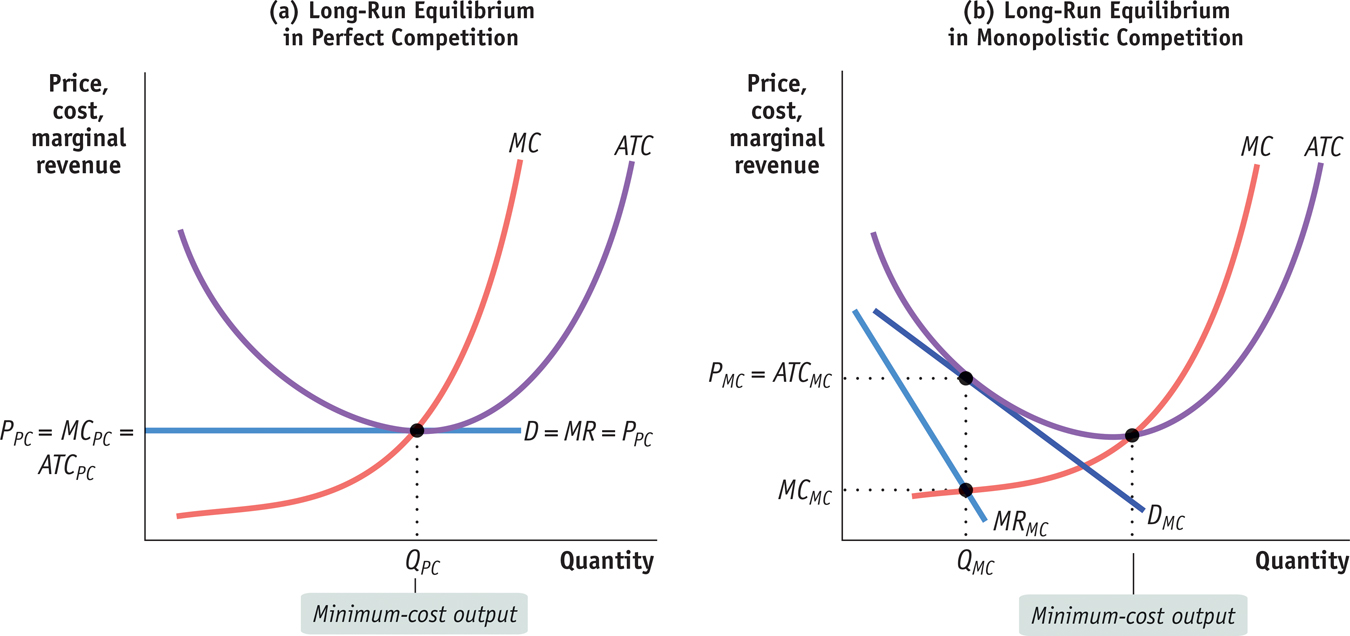

Figure 15-4 compares the long-run equilibrium of a typical firm in a perfectly competitive industry with that of a typical firm in a monopolistically competitive industry. Panel (a) shows a perfectly competitive firm facing a market price equal to its minimum average total cost; panel (b) reproduces Figure 15-3. Comparing the panels, we see two important differences.

Comparing Long-Run Equilibrium in Perfect Competition and Monopolistic Competition Panel (a) shows the situation of the typical firm in long-run equilibrium in a perfectly competitive industry. The firm operates at the minimum-cost output QPC, sells at the competitive market price PPC, and makes zero profit. It is indifferent to selling another unit of output because PPC is equal to its marginal cost, MCPC. Panel (b) shows the situation of the typical firm in long-run equilibrium in a monopolistically competitive industry. At QMC it makes zero profit because its price, PMC, just equals average total cost, ATCMC. At QMC the firm would like to sell another unit at price PMC since PMC exceeds marginal cost, MCMC. But it is unwilling to lower price to make more sales. It therefore operates to the left of the minimum-cost output level and has excess capacity.

First, in the case of the perfectly competitive firm shown in panel (a), the price, PPC, received by the firm at the profit-maximizing quantity, QPC, is equal to the firm’s marginal cost of production, MCPC, at that quantity of output. By contrast, at the profit-maximizing quantity chosen by the monopolistically competitive firm in panel (b), QMC, the price, PMC, is higher than the marginal cost of production, MCMC.

This difference translates into a difference in the attitude of firms toward consumers. A wheat farmer, who can sell as much wheat as he likes at the going market price, would not get particularly excited if you offered to buy some more wheat at the market price. Since he has no desire to produce more at that price and can sell the wheat to someone else, you are not doing him a favor.

But if you decide to fill up your tank at Jamil’s gas station rather than at Katy’s, you are doing Jamil a favor. He is not willing to cut his price to get more customers—he’s already made the best of that trade-off. But if he gets a few more customers than he expected at the posted price, that’s good news: an additional sale at the posted price increases his revenue more than it increases his costs because the posted price exceeds marginal cost.

The fact that monopolistic competitors, unlike perfect competitors, want to sell more at the going price is crucial to understanding why they engage in activities like advertising that help increase sales.

The other difference between monopolistic competition and perfect competition that is visible in Figure 15-4 involves the position of each firm on its average total cost curve. In panel (a), the perfectly competitive firm produces at point QPC, at the bottom of the U-shaped ATC curve. That is, each firm produces the quantity at which average total cost is minimized—the minimum-cost output. As a consequence, the total cost of industry output is also minimized.

Firms in a monopolistically competitive industry have excess capacity: they produce less than the output at which average total cost is minimized.

Under monopolistic competition, in panel (b), the firm produces at QMC, on the downward-sloping part of the U-shaped ATC curve: it produces less than the quantity that would minimize average total cost. This failure to produce enough to minimize average total cost is sometimes described as the excess capacity issue. The typical vendor in a food court or gas station along a road is not big enough to take maximum advantage of available cost savings. So the total cost of industry output is not minimized in the case of a monopolistically competitive industry.

Some people have argued that, because every monopolistic competitor has excess capacity, monopolistically competitive industries are inefficient. But the issue of efficiency under monopolistic competition turns out to be a subtle one that does not have a clear answer.