Why a Market Economy Produces Too Much Pollution

While pollution yields both benefits and costs to society, in a market economy without government intervention too much pollution will be produced. In that case it is polluters alone—

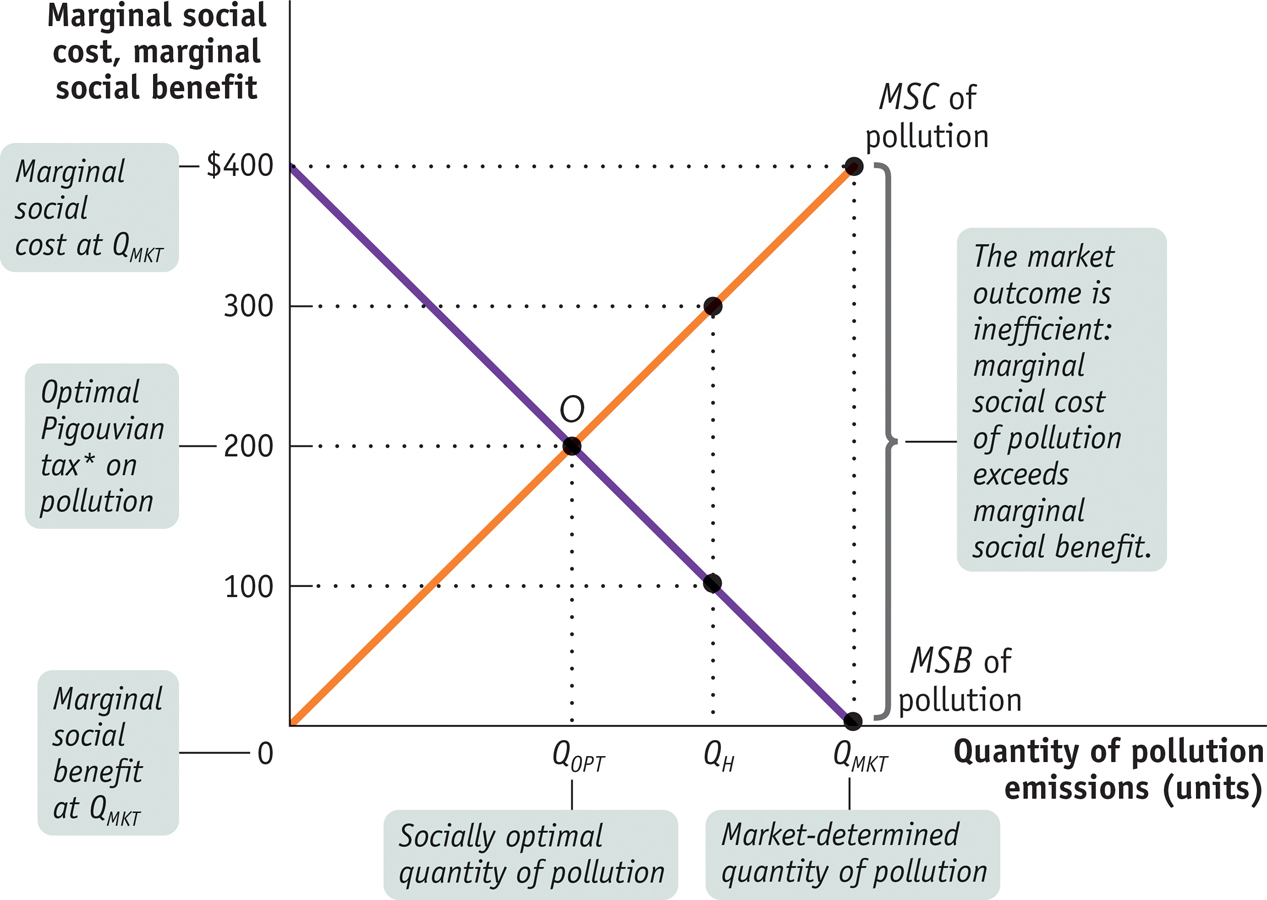

Figure 16-2 shows the result of this asymmetry between who reaps the benefits and who pays the costs. In a market economy without government intervention, since polluters are the only ones making the decisions, only the benefits of pollution are taken into account when choosing how much pollution to produce. So instead of producing the socially optimal quantity, QOPT, the market economy will generate the amount QMKT. At QMKT, the marginal social benefit of an additional unit of pollution is zero, while the marginal social cost of an additional unit is much higher—

Why? Well, take a moment to consider what the polluter would do if he found himself emitting QOPT of pollution. Remember that the MSB curve represents the resources made available by tolerating one more unit of pollution. The polluter would notice that if he increases his emission of pollution by moving down the MSB curve from QOPT to QH, he would gain $200 − $100 = $100. That gain of $100 comes from using less-

The market outcome, QMKT, is inefficient. Recall that an outcome is inefficient if someone could be made better off without someone else being made worse off. At an inefficient outcome, a mutually beneficial trade is being missed. At QMKT, the benefit accruing to the polluter of the last unit of pollution is very low—

So total surplus rises by approximately $400 if the quantity of pollution at QMKT is reduced by one unit. At QMKT, society would be willing to pay the polluter up to $400 not to emit the last unit of pollution, and the polluter would be willing to accept their offer since that last unit gains him virtually nothing. But because there is no means in this market economy for this transaction to take place, an inefficient outcome occurs.