Emissions Taxes

An emissions tax is a tax that depends on the amount of pollution a firm produces.

Another way to deal with pollution directly is to charge polluters an emissions tax. Emissions taxes are taxes that depend on the amount of pollution a firm emits. As we learned in Chapter 7, a tax imposed on an activity will reduce the level of that activity. Looking again at Figure 16-2, we can find the amount of tax on emissions that moves the market to the socially optiimal point. At QOPT, the socially optimal quantity of pollution, the marginal social benefit and marginal social cost of an additional unit of pollution is equal at $200. But in the absence of government intervention, polluters will push pollution up to the quantity QMKI, at which marginal social benefit is zero.

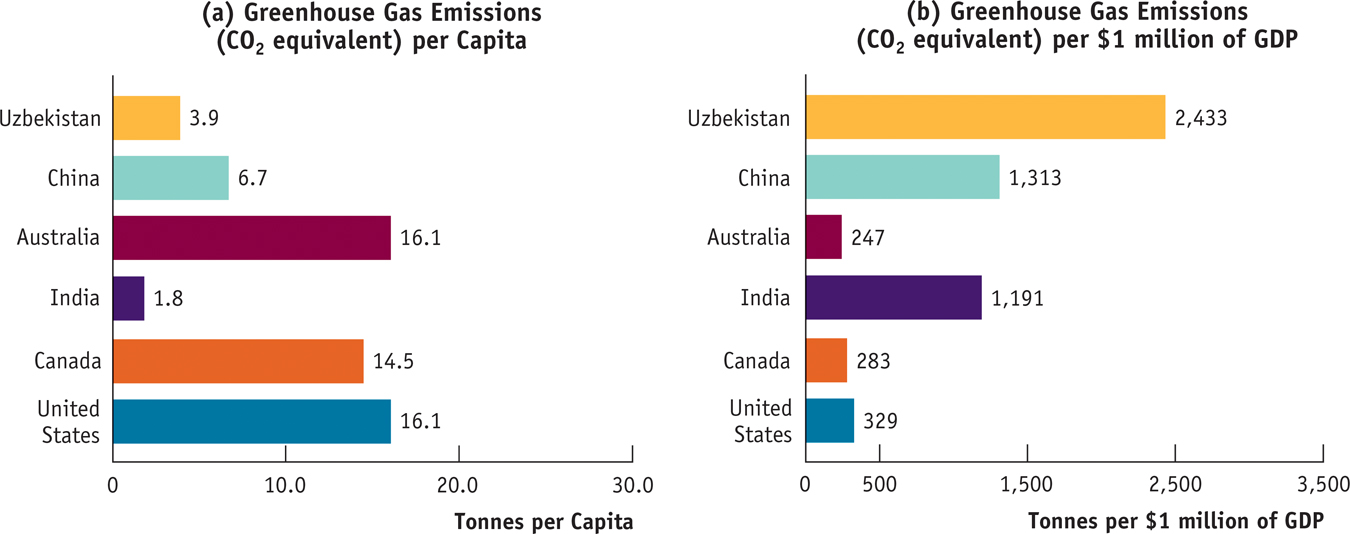

Economic Growth and Greenhouse Gases in Six Countries

At first glance, a comparison of the per capita greenhouse gas emissions of various countries, shown in panel (a) of this graph, suggests that Australia, Canada, and the United States are the worst offenders. The average American is responsible for 16.1 tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions (measured in CO2 equivalents)—the pollution that causes climate change—

Such a conclusion, however, ignores an important factor in determining the level of a country’s greenhouse gas emissions: its gross domestic product, or GDP—

A more meaningful way to compare pollution across countries is to measure emissions per $1 million of a country’s GDP, as shown in panel (b). On this basis, the United States, Canada, and Australia are now “green” countries, but China, India, and Uzbekistan are not. What explains the reversal once GDP is accounted for? The answer: both economics and government behavior.

First, there is the issue of economics. Countries that are poor and have begun to industrialize, such as China and Uzbekistan, often view money spent to reduce pollution as better spent on other things. From their perspective, they are still too poor to afford as clean an environment as wealthy advanced countries. They claim that to impose a wealthy country’s environmental standards on them would jeopardize their economic growth.

Second, there is the issue of government behavior—

Sources: Global Carbon Atlas; IMF—

It’s now easy to see how an emissions tax can solve the problem. If polluters are required to pay a tax of $200 per unit of pollution, they now face a marginal cost of $200 per unit and have an incentive to reduce their emissions to QOPT, the socially optimal quantity. This illustrates a general result: an emissions tax equal to the marginal social cost at the socially optimal quantity of pollution induces polluters to internalize the externality—

Taxes designed to reduce external costs are known as Pigouvian taxes.

The term emissions tax may convey the misleading impression that taxes are a solution to only one kind of external cost, pollution. In fact, taxes can be used to discourage any activity that generates negative externalities, such as driving (which inflicts environmental damage greater than the cost of producing gasoline) or smoking (which inflicts health costs on society far greater than the cost of making a cigarette). In general, taxes designed to reduce external costs are known as Pigouvian taxes, after the economist A. C. Pigou, who emphasized their usefulness in his classic 1920 book, The Economics of Welfare. In our example, the optimal Pigouvian tax is $200. As you can see from Figure 16-2, this corresponds to the marginal social cost of pollution at the optimal output quantity QOPT.

Are there any problems with emissions taxes? The main concern is that in practice government officials usually aren’t sure how high the tax should be set. If they set it too low, there won’t be sufficient reduction in pollution; if they set it too high, emissions will be reduced by more than is efficient. This uncertainty around the optimal level of the emissions tax can’t be eliminated, but the nature of the risks can be changed by using an alternative policy, issuing tradable emissions permits.