Cost-Benefit Analysis

Cost-

How do governments decide in practice how much of a public good to provide? Sometimes policy makers just guess—

It’s straightforward to estimate the cost of supplying a public good. Estimating the benefit is harder. In fact, it is a very difficult problem.

Now you might wonder why governments can’t figure out the marginal social benefit of a public good just by asking people their willingness to pay for it (their individual marginal benefit). But it turns out that it’s hard to get an honest answer.

This is not a problem with private goods: we can determine how much an individual is willing to pay for one more unit of a private good by looking at his or her actual choices. But because people don’t actually pay for public goods, the question of willingness to pay is always hypothetical.

Worse yet, it’s a question that people have an incentive not to answer truthfully. People naturally want more rather than less. Because they cannot be made to pay for whatever quantity of the public good they use, people are apt to overstate their true feelings when asked how much they desire a public good. For example, if street cleaning were scheduled according to the stated wishes of homeowners alone, the streets would be cleaned every day—

So governments must be aware that they cannot simply rely on the public’s statements when deciding how much of a public good to provide—

ECONOMICS in Action: Old Man River

Old Man River

It just keeps rolling along—

So when is the Mississippi due to change course again? Oh, about 45 years ago.

The Mississippi currently runs to the sea past New Orleans; but by 1950 it was apparent that the river was about to shift course, taking a new route to the sea. If the Army Corps of Engineers hadn’t gotten involved, the shift would probably have happened by 1970.

A shift in the Mississippi would have severely damaged the Louisiana economy. A major industrial area would have lost good access to the ocean, and salt water would have contaminated much of its water supply. So the Army Corps of Engineers has kept the Mississippi in its place with a huge complex of dams, walls, and gates known as the Old River Control Structure. At times the amount of water released by this control structure is five times the flow at Niagara Falls.

The Old River Control Structure is a dramatic example of a public good. No individual would have had an incentive to build it, yet it protects many billions of dollars’ worth of private property. The history of the Army Corps of Engineers, which handles water-

The flip-

Although it was well understood from the time of its founding that New Orleans was at risk for severe flooding because it sits below sea level, very little was done to shore up the crucial system of levees and pumps that protects the city. More than 50 years of inadequate funding for construction and maintenance, coupled with inadequate supervision, left the system weakened and unable to cope with the onslaught from Katrina. The catastrophe was compounded by the failure of local and state government to develop an evacuation plan in the event of a hurricane. In the end, because of this neglect of a public good, 1,464 people in and around New Orleans lost their lives and the city suffered economic losses totaling billions of dollars.

Quick Review

A public good is both nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption.

Because most forms of public-

good provision by the private sector have serious defects, they are typically provided by the government and paid for with taxes. The marginal social benefit of an additional unit of a public good is equal to the sum of each consumer’s individual marginal benefit from that unit. At the efficient quantity, the marginal social benefit equals the marginal cost of providing the good.

No individual has an incentive to pay for providing the efficient quantity of a public good because each individual’s marginal benefit is less than the marginal social benefit. This is a primary justification for the existence of government.

Although governments should rely on cost-

benefit analysis to determine how much of a public good to supply, doing so is problematic because individuals tend to overstate the good’s value to them.

17-2

Question 17.3

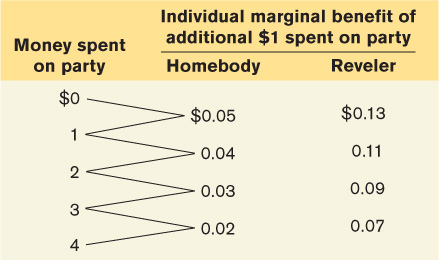

The town of Centreville, population 16, has two types of residents, Homebodies and Revelers. Using the accompanying table, the town must decide how much to spend on its New Year’s Eve party. No individual resident expects to directly bear the cost of the party.

Suppose there are 10 Homebodies and 6 Revelers. Determine the marginal social benefit schedule of money spent on the party. What is the efficient level of spending?

Suppose there are 6 Homebodies and 10 Revelers. How do your answers to part a change? Explain.

Suppose that the individual marginal benefit schedules are known but no one knows the true proportion of Homebodies versus Revelers. Individuals are asked their preferences. What is the likely outcome if each person assumes that others will pay for any additional amount of the public good? Why is it likely to result in an inefficiently high level of spending? Explain.

Solutions appear at back of book.