The Marginal Productivity Theory of Income Distribution

We’ve now seen that each perfectly competitive producer in a perfectly competitive factor market maximizes profit by hiring labor up to the point at which its value of the marginal product is equal to its price—

Let’s start by assuming that the labor market is in equilibrium: at the current market wage rate, the number of workers that producers want to employ is equal to the number of workers willing to work. Thus, all employers pay the same wage rate, and each employer, whatever he or she is producing, employs labor up to the point at which the value of the marginal product of the last worker hired is equal to the market wage rate.

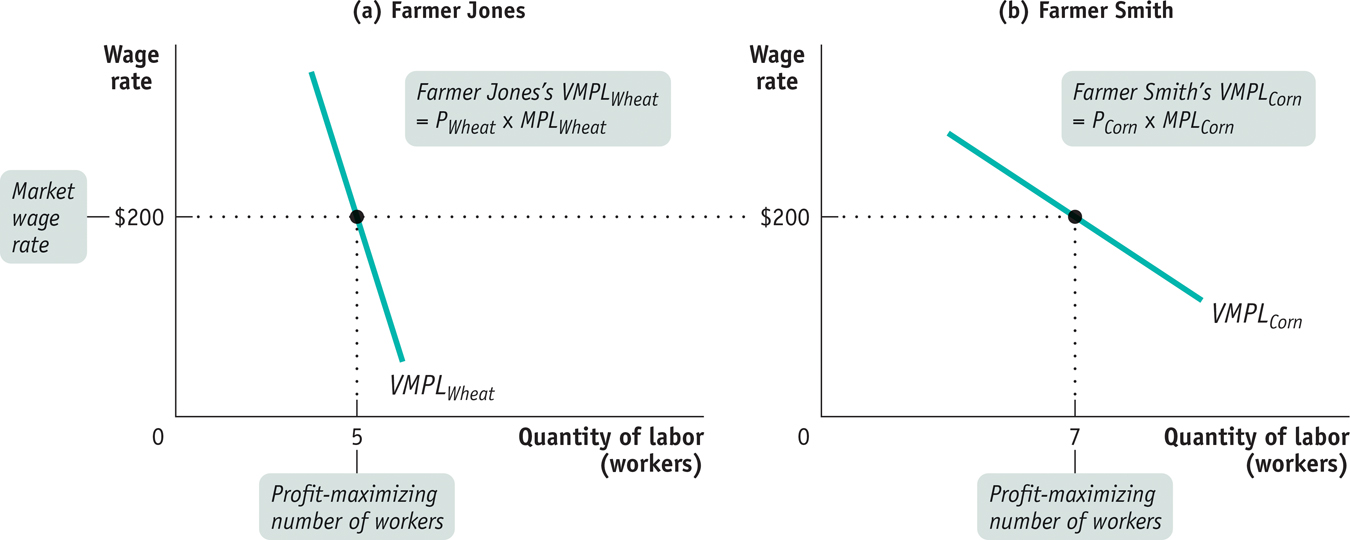

This situation is illustrated in Figure 19-5, which shows the value of the marginal product curves of two producers—

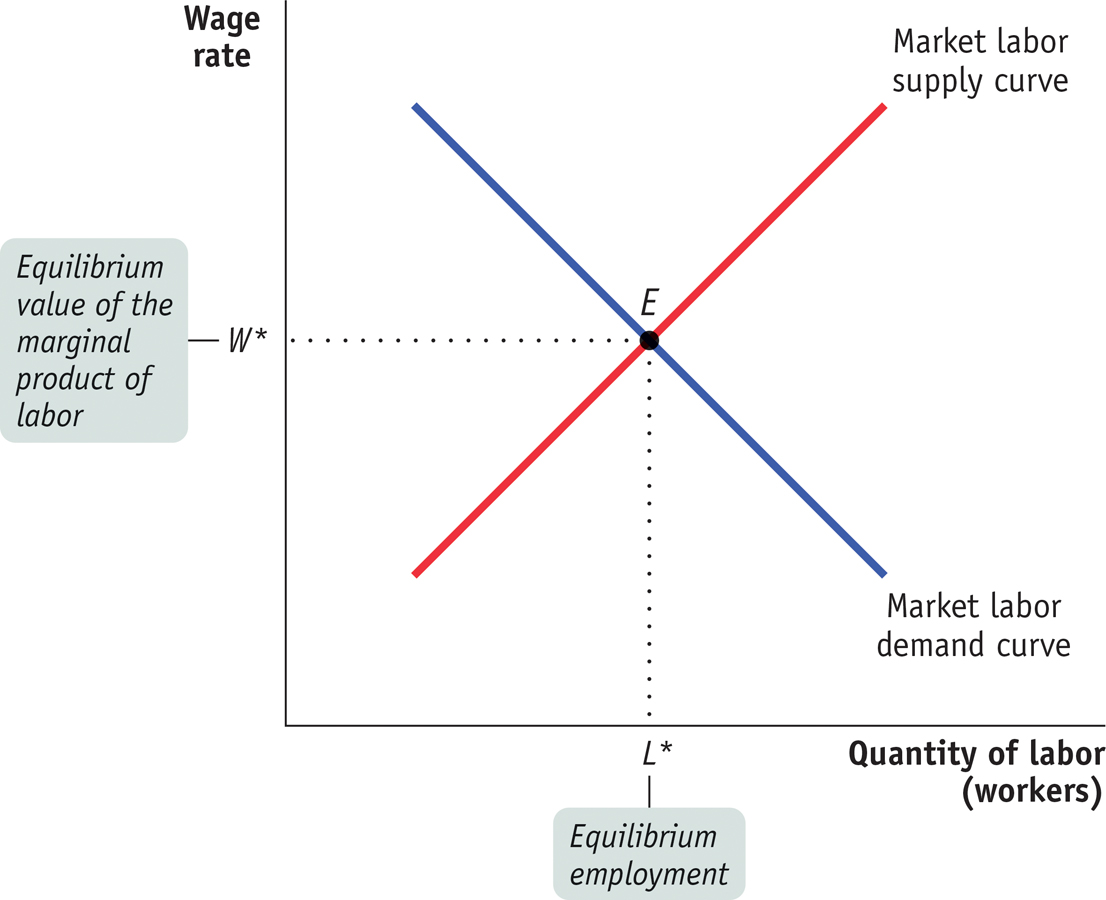

Figure 19-6 illustrates the labor market as a whole. The market labor demand curve, like the market demand curve for a good (shown in Figure 3-5), is the horizontal sum of all the individual labor demand curves of all the producers who hire labor. And recall that each producer’s individual labor demand curve is the same as his or her value of the marginal product of labor curve.

For now, let’s simply assume an upward-

The equilibrium value of the marginal product of a factor is the additional value produced by the last unit of that factor employed in the factor market as a whole.

And as we showed in the examples of the farms of George and Martha and of Farmer Jones and Farmer Smith (where the equilibrium wage rate is $200), each farm hires labor up to the point at which the value of the marginal product of labor is equal to the equilibrium wage rate. Therefore, in equilibrium, the value of the marginal product of labor is the same for all employers. So the equilibrium (or market) wage rate is equal to the equilibrium value of the marginal product of labor—

What we have just learned, then, is that the market wage rate is equal to the equilibrium value of the marginal product of labor. And the same is true of each factor of production: in a perfectly competitive market economy, the market price of each factor is equal to its equilibrium value of the marginal product. Let’s examine the markets for land and (physical) capital now. (From this point on, we’ll refer to physical capital as simply “capital.”)