Marginal Productivity and Wage Inequality

A large part of the observed inequality in wages can be explained by considerations that are consistent with the marginal productivity theory of income distribution. In particular, there are three well-understood sources of wage differences across occupations and individuals.

Compensating differentials are wage differences across jobs that reflect the fact that some jobs are less pleasant than others.

First is the existence of compensating differentials: across different types of jobs, wages are often higher or lower depending on how attractive or unattractive the job is. Workers with unpleasant or dangerous jobs demand a higher wage in comparison to workers with jobs that require the same skill and effort but lack the unpleasant or dangerous qualities. For example, truckers who haul hazardous loads are paid more than truckers who haul non-hazardous loads. But for any given job, the marginal productivity theory of income distribution generally holds true. For example, hazardous-load truckers are paid a wage equal to the equilibrium value of the marginal product of the last person employed in the labor market for hazardous-load truckers.

A second reason for wage inequality that is clearly consistent with marginal productivity theory is differences in talent. People differ in their abilities: a higher-ability person, by producing a better product that commands a higher price compared to a lower-ability person, generates a higher value of the marginal product. And these differences in the value of the marginal product translate into differences in earning potential. We all know that this is true in sports: practice is important, but 99.99% (at least) of the population just doesn’t have what it takes to throw passes like Tom Brady or hit tennis balls like Roger Federer. The same is true, though less obvious, in other fields of endeavor.

A third and very important reason for wage differences is differences in the quantity of human capital. Recall that human capital—education and training—is at least as important in the modern economy as physical capital in the form of buildings and machines. Different people “embody” quite different quantities of human capital, and a person with a higher quantity of human capital typically generates a higher value of the marginal product by producing a product that commands a higher price. So differences in human capital account for substantial differences in wages. People with high levels of human capital, such as skilled surgeons or engineers, generally receive high wages. In 2013, surgeons earned an average of $233,150.

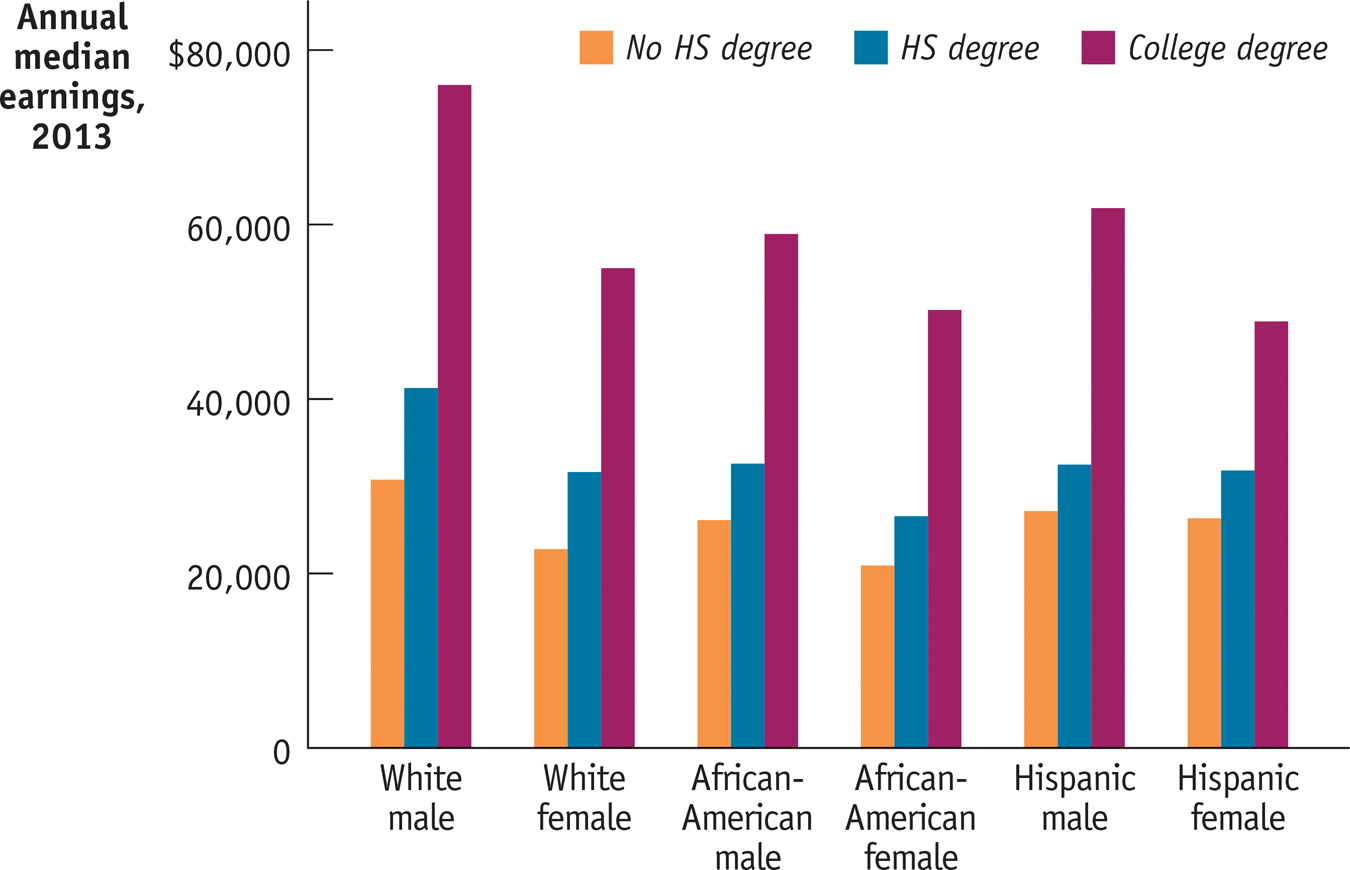

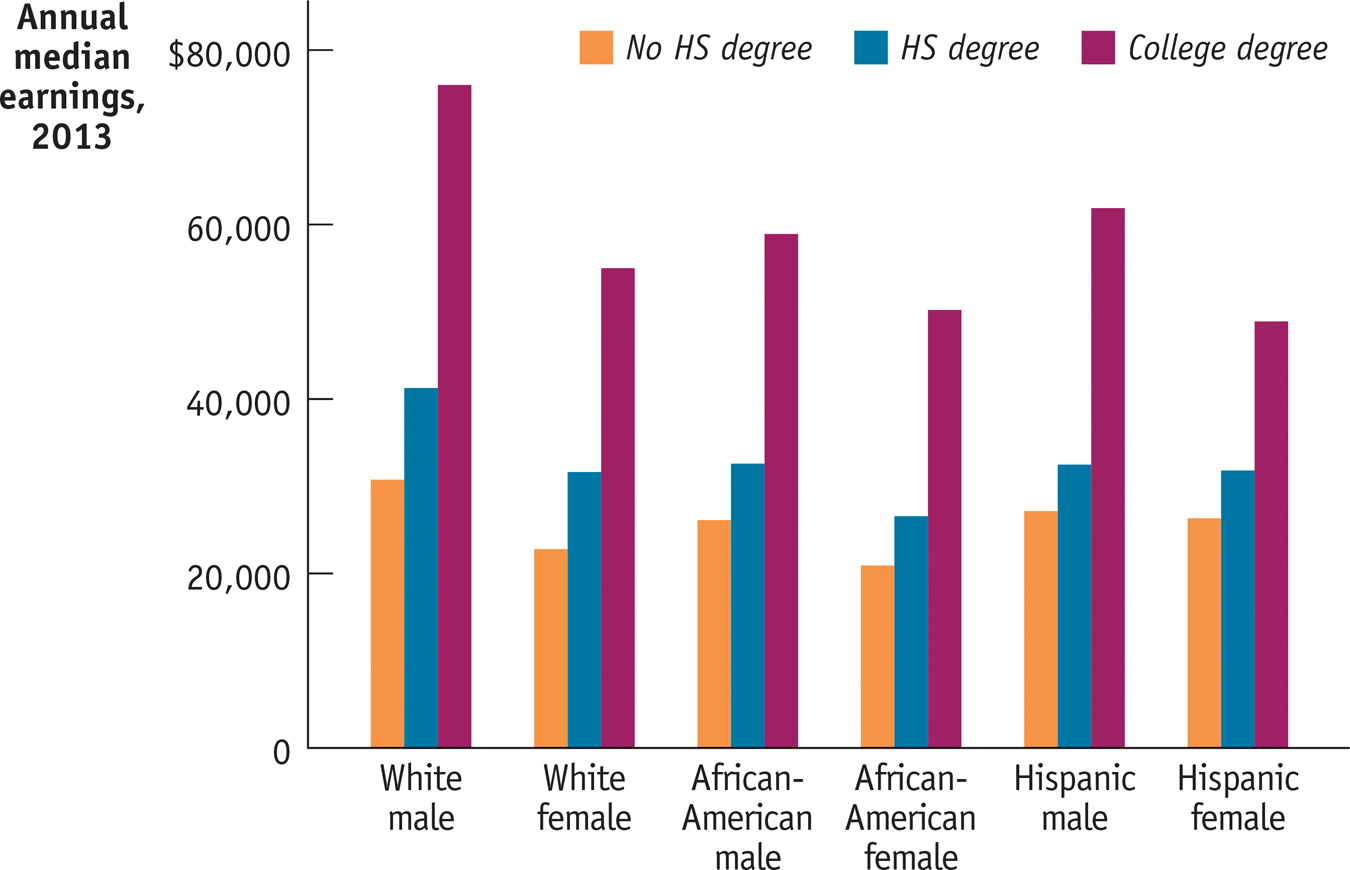

The most direct way to see the effect of human capital on wages is to look at the relationship between educational levels and earnings. Figure 19-9 shows earnings differentials by gender, ethnicity, and three educational levels for people age 25 or older in 2013. As you can see, regardless of gender or ethnicity, higher education is associated with higher median earnings. For example, in 2013 White females with 9 to 12 years of schooling but without a high school diploma had median earnings 28% less than those with a high school diploma and 65% less than those with a college degree—and similar patterns exist for the other five groups.

Earnings Differentials by Education, Gender, and Ethnicity, 2013 It is clear that, regardless of gender or ethnicity, education pays: those with a high school diploma earn more than those without one, and those with a college degree earn substantially more than those with only a high school diploma. Other patterns are evident as well: for any given education level, White males earn more than every other group, and males earn more than females for any given ethnic group.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

Because even now men typically have had more years of education than women and Whites more years than non-Whites, differences in level of education are part of the explanation for the earnings differences shown in Figure 19-8.

It’s important to realize that formal education is not the only source of human capital; on-the-job-training and work experience also generate human capital. In fact, there are other factors that also influence wage differences. A good illustration of these factors is found in research on the gender-wage gap, the persistent difference in the earnings of men compared to women. In the U.S. labor market, researchers have found that the gender gap is largely explained by differences in:

human capital (women tend to have lower levels of it)

choice of occupation (women tend to choose occupations such as nursing and teaching in which they earn less)

career interruptions (women move in and out of labor force more frequently)

part-time status (women are more likely to work part-time instead of full-time)

overtime status (women are less likely to work overtime)

For example, in a U.S. Department of Labor study using recent census data, the gender-wage gap fell from 20.4% to 5% once these five factors were accounted for. Moreover, over the past 30 years even the unadjusted gender-wage gap has fallen significantly, from 36.5% in 1979 to 16.5% in 2011, as women have begun to close in on men in terms of these five factors.

But it’s also important to emphasize that earnings differences arising from these factors are not necessarily “fair.” When women do most of the work caring for children, they will inevitably have more career interruptions or need to work part-time instead of full-time. Similarly, a society where non-White children typically receive a poor education because they live in underfunded school districts, then go on to earn low wages because they are poorly educated, may have labor markets that are well described by marginal productivity theory (and would be consistent with the earnings differentials across ethnic groups and between the genders shown in Figure 19-8). Yet many people would still consider the resulting distribution of income unfair.

Still, many observers think that actual wage differentials cannot be entirely explained by compensating differentials, differences in talent, differences in human capital, or differences in job status. They believe that market power, efficiency wages, and discrimination also play an important role. We will examine these forces next.