Value of the Marginal Product

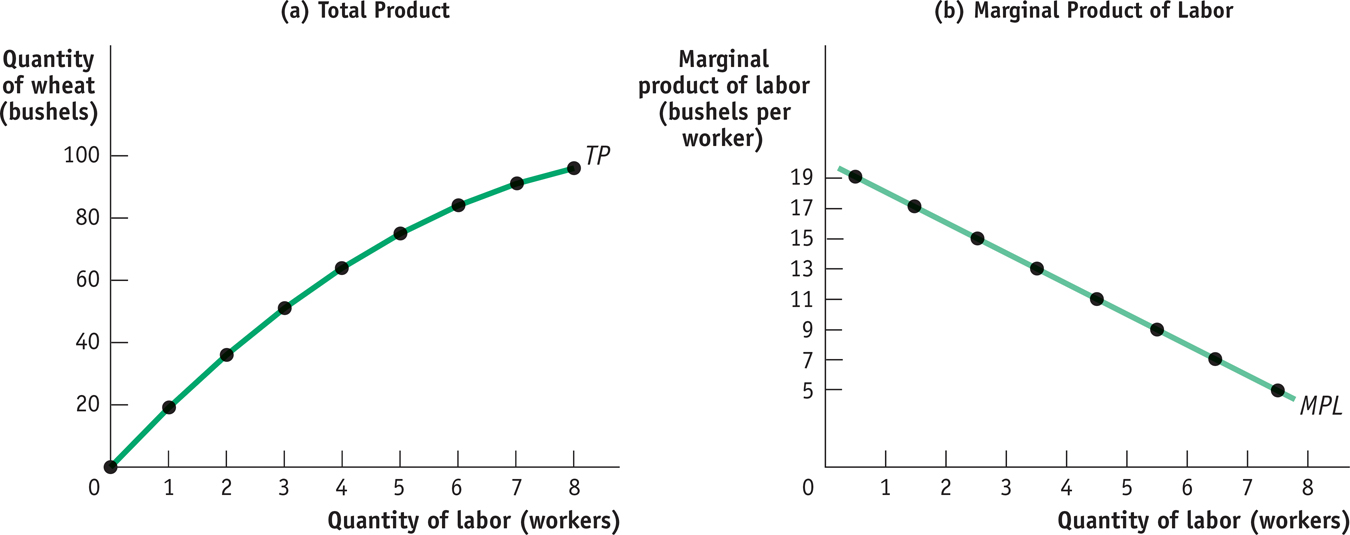

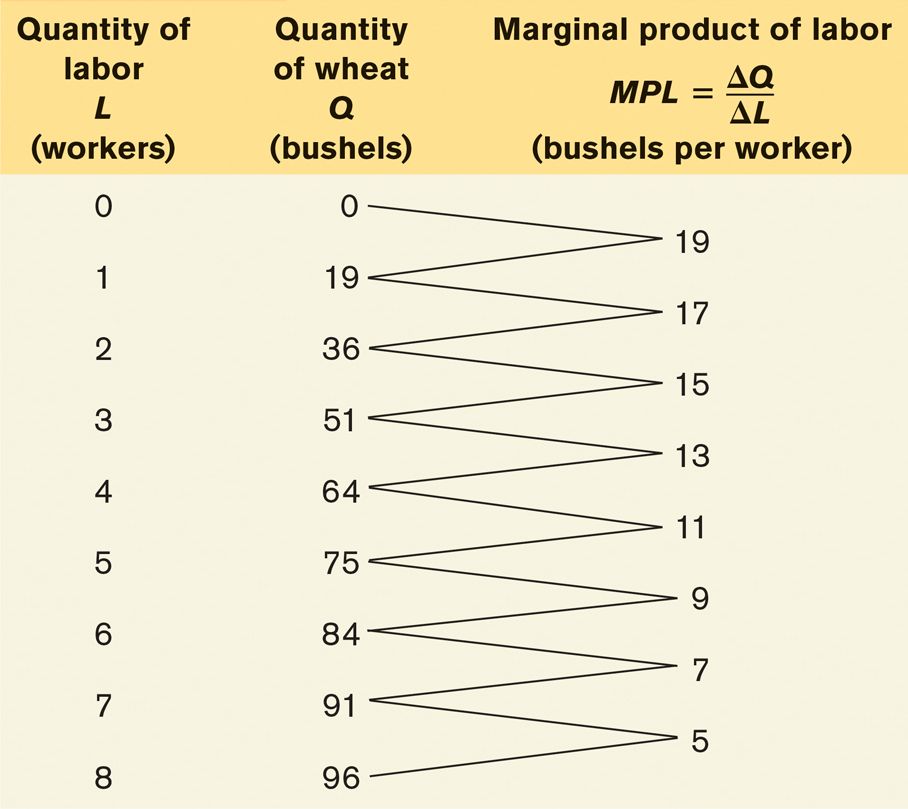

Figure 19-2 reproduces Figures 11-1 and 11-2, which showed the production function for wheat on George and Martha’s farm. Panel (a) uses the total product curve to show how total wheat production depends on the number of workers employed on the farm; panel (b) shows how the marginal product of labor, the increase in output from employing one more worker, depends on the number of workers employed. Table 19-1, which reproduces the table in Figure 11-1, shows the numbers behind the figure.

Assume that George and Martha want to maximize their profit, that workers must be paid $200 each, and that wheat sells for $20 per bushel. What is their optimal number of workers? That is, how many workers should they employ to maximize profit?

In Chapters 11 and 12 we showed how to answer this question in several steps. In Chapter 11 we used information from the producer’s production function to derive the firm’s total cost and its marginal cost. And in Chapter 12 we derived the price-

There is, however, another way to use marginal analysis to find the number of workers that maximizes a producer’s profit. We can go directly to the question of what level of employment maximizes profit. This alternative approach is equivalent to the approach we outlined in the preceding paragraph—

The value of the marginal product of a factor is the value of the additional output generated by employing one more unit of that factor.

To see how this alternative approach works, let’s suppose that George and Martha are considering whether or not to employ an additional worker. The increase in cost from employing that additional worker is the wage rate, W. The benefit to George and Martha from employing that extra worker is the value of the extra output that worker can produce. What is this value? It is the marginal product of labor, MPL, multiplied by the price per unit of output, P. This amount—

(19-

So should George and Martha hire that extra worker? The answer is yes if the value of the extra output is more than the cost of the worker—

So the decision to hire labor is a marginal decision, in which the marginal benefit to the producer from hiring an additional worker (VMPL) should be compared with the marginal cost to the producer (W). And as with any marginal decision, the optimal choice is where marginal benefit is just equal to marginal cost. That is, to maximize profit George and Martha will employ workers up to the point at which, for the last worker employed:

(19-

This rule doesn’t apply only to labor; it applies to any factor of production. The value of the marginal product of any factor is its marginal product times the price of the good it produces. The general rule is that a profit-

It’s important to realize that this rule doesn’t conflict with our analysis in Chapters 11 and 12. There we saw that a profit-

Now let’s look more closely at why choosing the level of employment at which the value of the marginal product of the last worker employed is equal to the wage rate works—