Willingness to Pay and Consumer Surplus

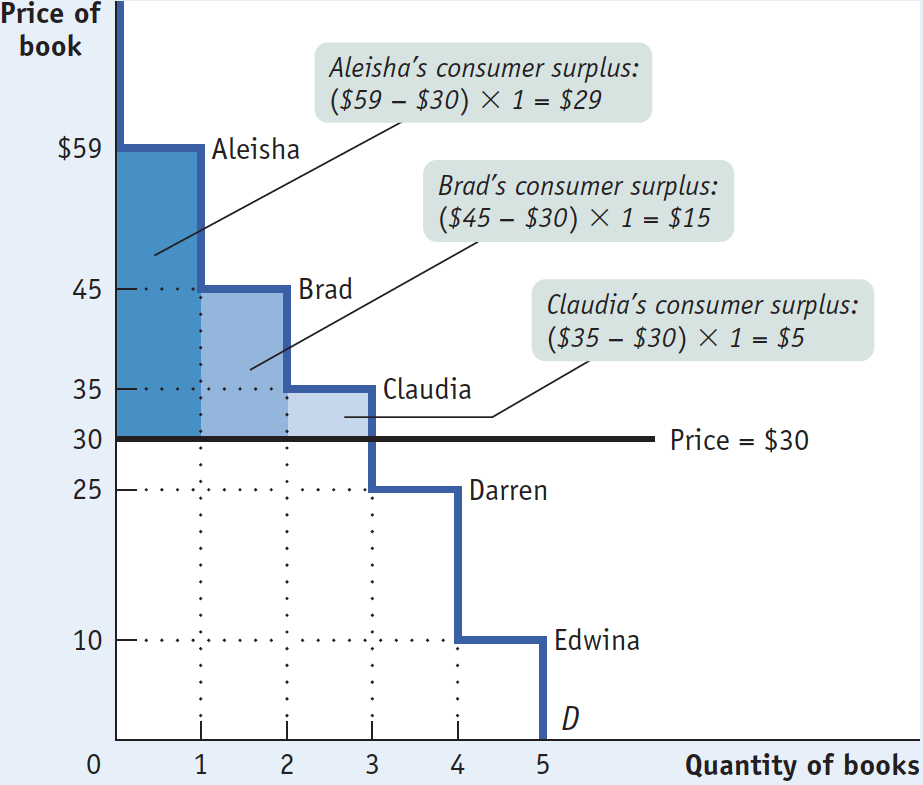

Suppose that the campus bookstore makes used textbooks available at a price of $30. In that case Aleisha, Brad, and Claudia will buy books. Do they gain from their purchases, and if so, how much?

The answer, shown in Table 4-1, is that each student who purchases a book does achieve a net gain but that the amount of the gain differs among students.

|

Potential buyer |

Willingness to pay |

Price paid |

Individual consumer surplus = Willingness to pay – Price paid |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Aleisha |

$59 |

$30 |

$29 |

|

Brad |

45 |

30 |

15 |

|

Claudia |

35 |

30 |

5 |

|

Darren |

25 |

– |

– |

|

Edwina |

10 |

– |

– |

|

All buyers |

Total consumer surplus = $49 |

Aleisha would have been willing to pay $59, so her net gain is $59 − $30 = $29. Brad would have been willing to pay $45, so his net gain is $45 − $30 = $15. Claudia would have been willing to pay $35, so her net gain is $35 − $30 = $5. Darren and Edwina, however, won’t be willing to buy a used book at a price of $30, so they neither gain nor lose.

Individual consumer surplus is the net gain to an individual buyer from the purchase of a good. It is equal to the difference between the buyer’s willingness to pay and the price paid.

The net gain that a buyer achieves from the purchase of a good is called that buyer’s individual consumer surplus. What we learn from this example is that whenever a buyer pays a price less than his or her willingness to pay, the buyer achieves some individual consumer surplus.

Total consumer surplus is the sum of the individual consumer surpluses of all the buyers of a good in a market.

The sum of the individual consumer surpluses achieved by all the buyers of a good is known as the total consumer surplus achieved in the market. In Table 4-1, the total consumer surplus is the sum of the individual consumer surpluses achieved by Aleisha, Brad, and Claudia: $29 + $15 + $5 = $49.

The term consumer surplus is often used to refer both to individual and to total consumer surplus.

Economists often use the term consumer surplus to refer to both individual and total consumer surplus. We will follow this practice; it will always be clear in context whether we are referring to the consumer surplus achieved by an individual or by all buyers.

Total consumer surplus can be represented graphically. Figure 4-2 reproduces the demand curve from Figure 4-1. Each step in that demand curve is one book wide and represents one consumer. For example, the height of Aleisha’s step is $59, her willingness to pay. This step forms the top of a rectangle, with $30—

In addition to Aleisha, Brad and Claudia will also each buy a book when the price is $30. Like Aleisha, they benefit from their purchases, though not as much, because they each have a lower willingness to pay. Figure 4-2 also shows the consumer surplus gained by Brad and Claudia; again, this can be measured by the areas of the appropriate rectangles. Darren and Edwina, because they do not buy books at a price of $30, receive no consumer surplus.

The total consumer surplus achieved in this market is just the sum of the individual consumer surpluses received by Aleisha, Brad, and Claudia. So total consumer surplus is equal to the combined area of the three rectangles—

Figure 4-2 illustrates the following general principle: The total consumer surplus generated by purchases of a good at a given price is equal to the area below the demand curve but above that price. The same principle applies regardless of the number of consumers.

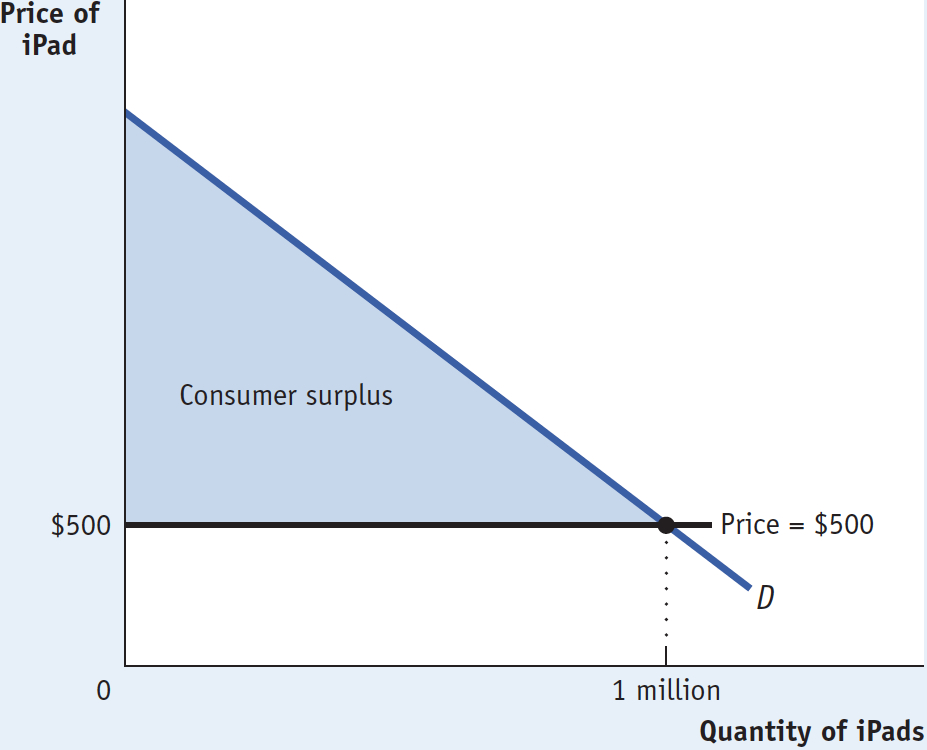

When we consider large markets, this graphical representation of consumer surplus becomes extremely helpful. Consider, for example, the sales of iPads to millions of potential buyers. Each potential buyer has a maximum price that he or she is willing to pay. With so many potential buyers, the demand curve will be smooth, like the one shown in Figure 4-3.

Suppose that at a price of $500, a total of 1 million iPads are purchased. How much do consumers gain from being able to buy those 1 million iPads? We could answer that question by calculating the individual consumer surplus of each buyer and then adding these numbers up to arrive at a total. But it is much easier just to look at Figure 4-3 and use the fact that total consumer surplus is equal to the shaded area. As in our original example, consumer surplus is equal to the area below the demand curve but above the price. (To refresh your memory on how to calculate the area of a right triangle, see the appendix to Chapter 2.)