How a Price Ceiling Causes Inefficiency

The housing shortage shown in Figure 5-2 is not merely annoying: like any shortage induced by price controls, it can be seriously harmful because it leads to inefficiency. In other words, there are gains from trade that go unrealized.

Rent control, like all price ceilings, creates inefficiency in at least four distinct ways.

It reduces the quantity of apartments rented below the efficient level.

It typically leads to inefficient allocation of apartments among would-

be renters. It leads to wasted time and effort as people search for apartments.

It leads landlords to maintain apartments in inefficiently low quality or condition.

In addition to inefficiency, price ceilings give rise to illegal behavior as people try to circumvent them. We’ll now look at each of these inefficiencies caused by price ceilings.

Inefficiently Low Quantity In Chapter 4 we learned that the market equilibrium of an efficient market leads to the “right” quantity of a good or service being bought and sold—

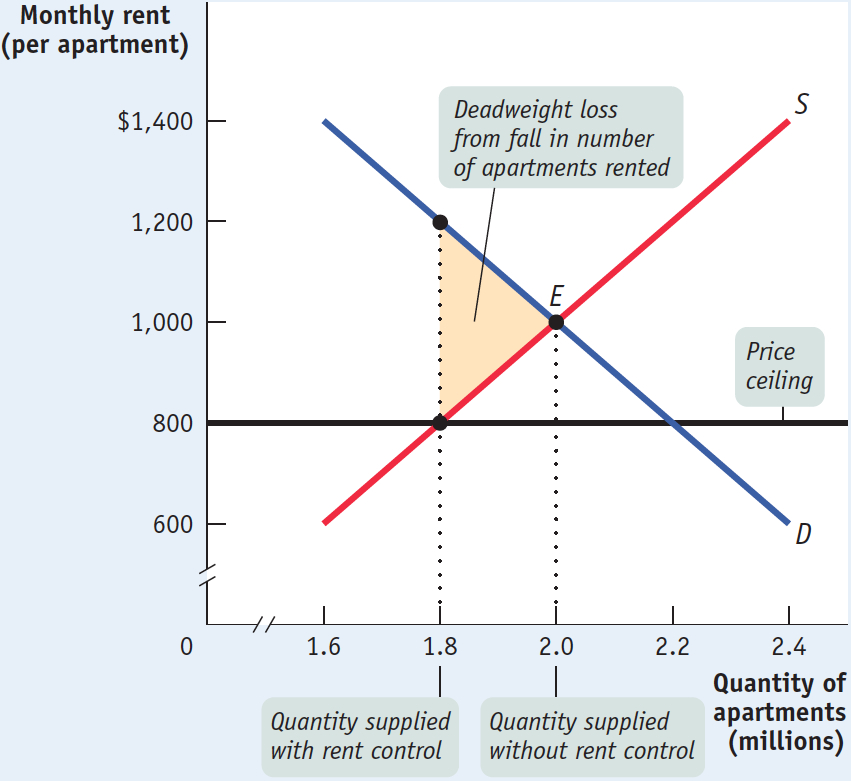

Figure 5-3 shows the implications for total surplus. Recall that total surplus is the sum of the area above the supply curve and below the demand curve. If the only effect of rent control was to reduce the number of apartments available, it would cause a loss of surplus equal to the area of the shaded triangle in the figure.

Deadweight loss is the loss in total surplus that occurs whenever an action or a policy reduces the quantity transacted below the efficient market equilibrium quantity.

The area represented by that triangle has a special name in economics, deadweight loss: the lost surplus associated with the transactions that no longer occur due to the market intervention. In this example, the deadweight loss is the lost surplus associated with the apartment rentals that no longer occur due to the price ceiling, a loss that is experienced by both disappointed renters and frustrated landlords. Economists often call triangles like the one in Figure 5-3 a deadweight-

Deadweight loss is a key concept in economics, one that we will encounter whenever an action or a policy leads to a reduction in the quantity transacted below the efficient market equilibrium quantity. It is important to realize that deadweight loss is a loss to society—it is a reduction in total surplus, a loss in surplus that accrues to no one as a gain. It is not the same as a loss in surplus to one person that then accrues as a gain to someone else, what an economist would call a transfer of surplus from one person to another. For an example of how a price ceiling can create deadweight loss as well as a transfer of surplus between renters and landlords, see the upcoming For Inquiring Minds.

Deadweight loss is not the only type of inefficiency that arises from a price ceiling. The types of inefficiency created by rent control go beyond reducing the quantity of apartments available. These additional inefficiencies—

FOR INQUIRING MINDS: Winners, Losers, and Rent Control

Price controls create winners and losers: some people benefit from the policy but others are made worse off.

In New York City, some of the biggest beneficiaries of rent control are affluent tenants who have lived for decades in choice apartments that would now command very high rents. These winners include celebrities like actor Al Pacino and the singer and songwriter Cyndi Lauper. Similarly, in 2014, there were stories in the news citing the cases of rent-

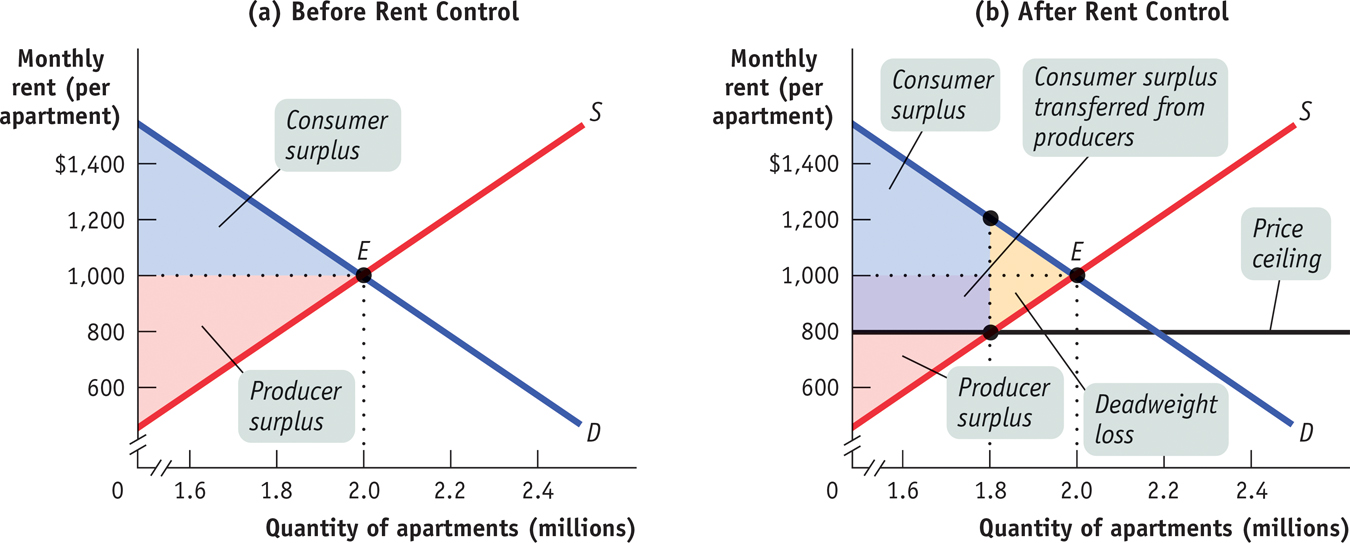

We can use the concepts of consumer and producer surplus, which you learned about in Chapter 4, to graphically evaluate the winners and the losers from rent control. Panel (a) of Figure 5-4 shows the consumer surplus and producer surplus in the equilibrium of the unregulated market for apartments—

Panel (b) of this figure shows the consumer and producer surplus in the market after the price ceiling of $800 has been imposed. As you can see, for consumers who can still obtain apartments under rent control, consumer surplus has increased. These renters are clearly winners: they obtain an apartment at $800, paying $200 less than the unregulated market price. These people receive a direct transfer of surplus from landlords in the form of lower rent. But not all renters win: there are fewer apartments to rent now than if the market had remained unregulated, making it hard, if not impossible, for some to find a place to call home.

Without direct calculation of the surpluses gained and lost, it is generally unclear whether renters as a whole are made better or worse off by rent control. What we can say is that the greater the deadweight loss—

However, we can say unambiguously that landlords are worse off: producer surplus has clearly decreased. Landlords who continue to rent out their apartments get $200 a month less in rent, and others withdraw their apartments from the market altogether. The deadweight-

Inefficient Allocation to Consumers Rent control doesn’t just lead to too few apartments being available. It can also lead to misallocation of the apartments that are available: people who badly need a place to live may not be able to find an apartment, but some apartments may be occupied by people with much less urgent needs.

In the case shown in Figure 5-2, 2.2 million people would like to rent an apartment at $800 per month, but only 1.8 million apartments are available. Of those 2.2 million who are seeking an apartment, some want one badly and are willing to pay a high price to get it. Others have a less urgent need and are only willing to pay a low price, perhaps because they have alternative housing.

An efficient allocation of apartments would reflect these differences: people who really want an apartment will get one and people who aren’t all that anxious to find an apartment won’t. In an inefficient distribution of apartments, the opposite will happen: some people who are not especially anxious to find an apartment will get one and others who are very anxious to find an apartment won’t.

Price ceilings often lead to inefficiency in the form of inefficient allocation to consumers: some people who want the good badly and are willing to pay a high price don’t get it, and some who care relatively little about the good and are only willing to pay a low price do get it.

Because people usually get apartments through luck or personal connections under rent control, it generally results in an inefficient allocation to consumers of the few apartments available.

To see the inefficiency involved, consider the plight of the Lees, a family with young children who have no alternative housing and would be willing to pay up to $1,500 for an apartment—

This allocation of apartments—

Generally, if people who really want apartments could sublease them from people who are less eager to live there, both those who gain apartments and those who trade their occupancy for money would be better off. However, subletting is illegal under rent control because it would occur at prices above the price ceiling.

The fact that subletting is illegal doesn’t mean it never happens. In fact, chasing down illegal subletting is a major business for New York private investigators. An article in the New York Times described how private investigators use hidden cameras and other tricks to prove that the legal tenants in rent-

This subletting is a kind of illegal activity, which we will discuss shortly. For now, just note that landlords and legal agencies actively discourage the practice. As a result, the problem of inefficient allocation of apartments remains.

Price ceilings typically lead to inefficiency in the form of wasted resources: people expend money, effort, and time to cope with the shortages caused by the price ceiling.

Wasted Resources Another reason a price ceiling causes inefficiency is that it leads to wasted resources: people expend money, effort, and time to cope with the shortages caused by the price ceiling. Back in 1979, U.S. price controls on gasoline led to shortages that forced millions of Americans to wait on lines at gas stations for hours each week. The opportunity cost of the time spent in gas lines—

Because of rent control, the Lees will spend all their spare time for several months searching for an apartment, time they would rather have spent working or in family activities. That is, there is an opportunity cost to the Lees’ prolonged search for an apartment—

If the market for apartments worked freely, the Lees would quickly find an apartment at the equilibrium rent of $1,000, leaving them time to earn more or to enjoy themselves—

Price ceilings often lead to inefficiency in that the goods being offered are of inefficiently low quality: sellers offer low-

Inefficiently Low Quality Yet another way a price ceiling creates inefficiency is by causing goods to be of inefficiently low quality. Inefficiently low quality means that sellers offer low-

Again, consider rent control. Landlords have no incentive to provide better conditions because they cannot raise rents to cover their repair costs but are able to find tenants easily. In many cases, tenants would be willing to pay much more for improved conditions than it would cost for the landlord to provide them—

!worldview! FOR INQUIRING MINDS: Mumbai’s Rent-Control Millionaires

Just how costly is rent control for landlords? In Mumbai, India, the answer is very high indeed. It is so high that thousands of rent-

In Mumbai, a magnet for a rapidly expanding number of high-

Take the case of Mea Kadwani, age 78, who had been living since he was a toddler in the same 2,600-

But not all rent-

Rent control began in Mumbai in 1947 to address a crucial shortage of housing caused by a flood of refugees fleeing conflict between Hindus and Muslims. Clearly intended as a temporary measure, it was so popular politically that it has been extended 20 times and now applies to about 60% of the buildings in the city’s center. Tenants pass apartments on to heirs or sell the right to occupy to others. Landlords, who often are paying more in taxes and upkeep than they receive in rents, suffer financially and sometimes simply abandon their properties.

So although it’s a world away, the dynamics of rent control in Mumbai are similar to those in New York where many rent-

So common is the experience in New York and other cities that it was the subject of a Law and Order episode in which a landlord is investigated for the murder of a rent-

Indeed, rent-

This whole situation is a missed opportunity—

A black market is a market in which goods or services are bought and sold illegally—

Black Markets In addition to these four inefficiencies there is a final aspect of price ceilings: the incentive they provide for illegal activities, specifically the emergence of black markets. We have already described one kind of black market activity—

What’s wrong with black markets? In general, it’s a bad thing if people break any law, because it encourages disrespect for the law in general. Worse yet, in this case illegal activity worsens the position of those who are honest. If the Lees are scrupulous about upholding the rent-