How a Price Floor Causes Inefficiency

The persistent surplus that results from a price floor creates missed opportunities—

It creates deadweight loss by reducing the quantity transacted to below the efficient level.

It leads to an inefficient allocation of sales among sellers.

It leads to a waste of resources.

It leads to sellers providing an inefficiently high-

quality level.

In addition to inefficiency, like a price ceiling, a price floor leads to illegal behavior as people break the law to sell below the legal price.

Inefficiently Low Quantity Because a price floor raises the price of a good to consumers, it reduces the quantity of that good demanded; because sellers can’t sell more units of a good than buyers are willing to buy, a price floor reduces the quantity of a good bought and sold below the market equilibrium quantity and leads to a deadweight loss. Notice that this is the same effect as a price ceiling. You might be tempted to think that a price floor and a price ceiling have opposite effects, but both have the effect of reducing the quantity of a good bought and sold (as you can see in the accompanying Pitfalls).

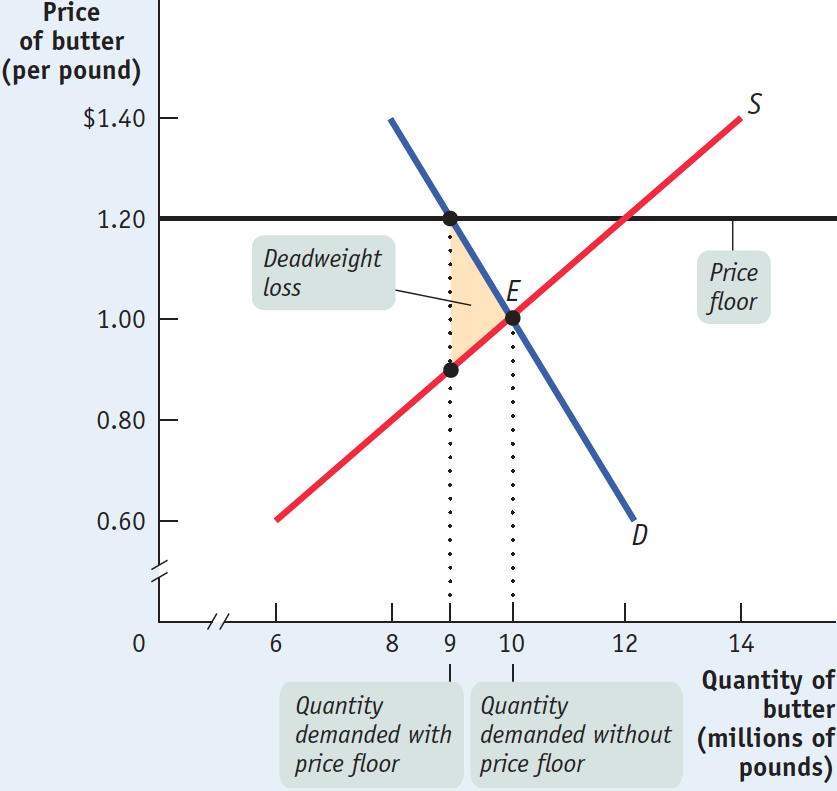

Since the equilibrium of an efficient market maximizes the sum of consumer and producer surplus, a price floor that reduces the quantity below the equilibrium quantity reduces total surplus. Figure 5-7 shows the implications for total surplus of a price floor on the price of butter. Total surplus is the sum of the area above the supply curve and below the demand curve. By reducing the quantity of butter sold, a price floor causes a deadweight loss equal to the area of the shaded triangle in the figure. As in the case of a price ceiling, however, deadweight loss is only one of the forms of inefficiency that the price control creates.

PITFALLS: CEILINGS, FLOORS, AND QUANTITIES

CEILINGS, FLOORS, AND QUANTITIES

A price ceiling pushes the price of a good down. A price floor pushes the price of a good up. So it’s easy to assume that the effects of a price floor are the opposite of the effects of a price ceiling. In particular, if a price ceiling reduces the quantity of a good bought and sold, doesn’t a price floor increase the quantity?

No, it doesn’t. In fact, both floors and ceilings reduce the quantity bought and sold. Why? When the quantity of a good supplied isn’t equal to the quantity demanded, the actual quantity sold is determined by the “short side” of the market—

Price floors can lead to inefficient allocation of sales among sellers: sellers who are willing to sell at the lowest price are unable to make sales while sales go to sellers who are only willing to sell at a higher price.

Inefficient Allocation of Sales Among Sellers Like a price ceiling, a price floor can lead to inefficient allocation—in this case, an inefficient allocation of sales among sellers: sellers who are willing to sell at the lowest price are unable to make sales, while sales go to sellers who are only willing to sell at a higher price.

One illustration of the inefficient allocation of selling opportunities caused by a price floor is the problem of unemployment and the black market for labor among the young in many European countries—

Wasted Resources Also like a price ceiling, a price floor generates inefficiency by wasting resources. The most graphic examples involve government purchases of the unwanted surpluses of agricultural products caused by price floors. The surplus production is sometimes destroyed, which is pure waste; in other cases, the stored produce goes, as officials euphemistically put it, “out of condition” and must be thrown away.

Price floors also lead to wasted time and effort. Consider the minimum wage. Would-

Inefficiently High Quality Again like price ceilings, price floors lead to inefficiency in the quality of goods produced.

Price floors often lead to inefficiency in that goods of inefficiently high quality are offered: sellers offer high-

We saw that when there is a price ceiling, suppliers produce products that are of inefficiently low quality: buyers prefer higher-

How can this be? Isn’t high quality a good thing? Yes, but only if it is worth the cost. Suppose that suppliers spend a lot to make goods of very high quality but that this quality isn’t worth much to consumers, who would rather receive the money spent on that quality in the form of a lower price. This represents a missed opportunity: suppliers and buyers could make a mutually beneficial deal in which buyers got goods of lower quality for a much lower price.

A good example of the inefficiency of excessive quality comes from the days when transatlantic airfares were set artificially high by international treaty. Forbidden to compete for customers by offering lower ticket prices, airlines instead offered expensive services, like lavish in-

Since the deregulation of U.S. airlines in the 1970s, American passengers have experienced a large decrease in ticket prices accompanied by a decrease in the quality of in-

Illegal Activity In addition to the four inefficiencies we analyzed, like price ceilings, price floors provide incentives for illegal activity. For example, in countries where the minimum wage is far above the equilibrium wage rate, workers desperate for jobs sometimes agree to work off the books for employers who conceal their employment from the government—

Check Out Our Low, Low Wages!

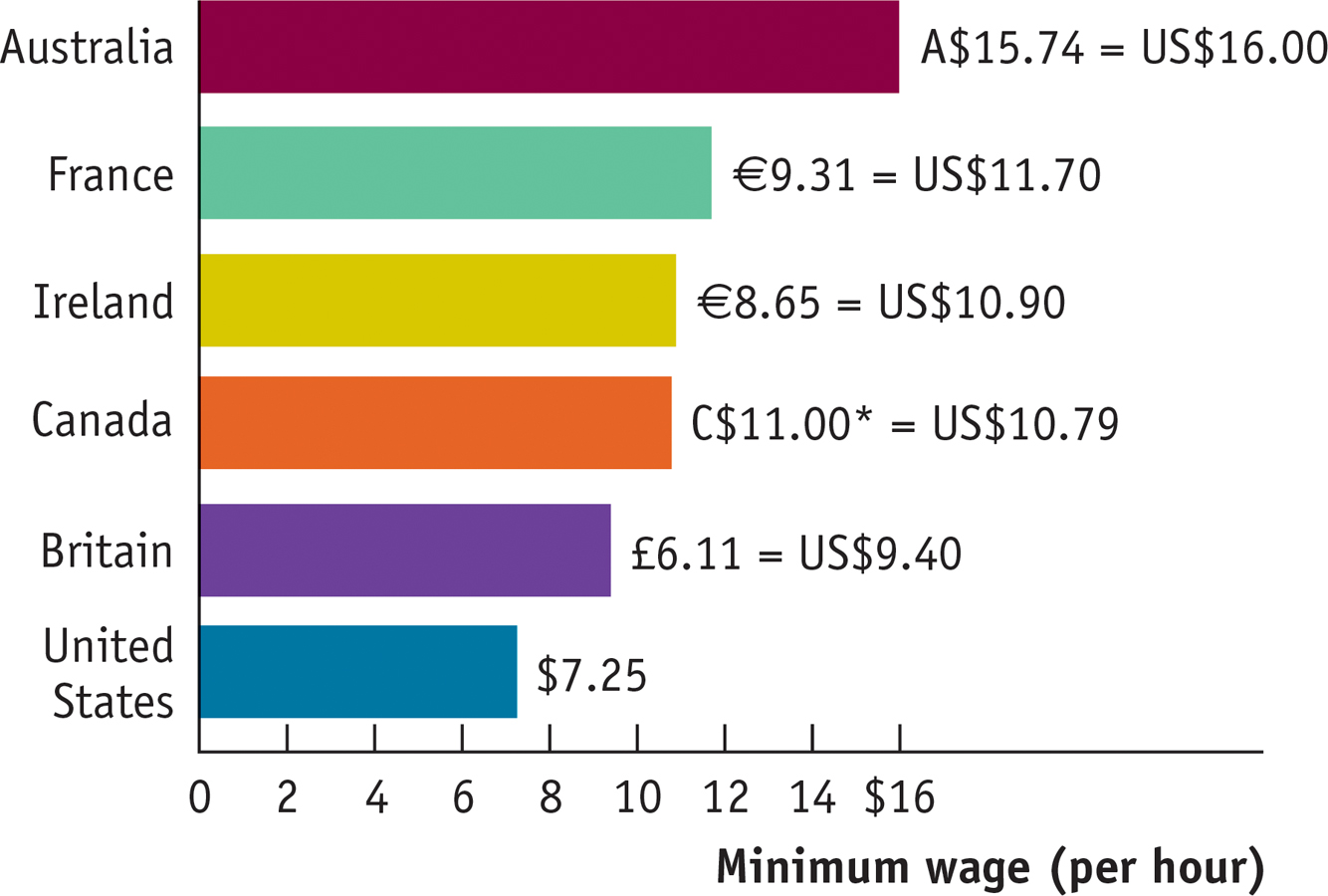

The minimum wage rate in the United States, as you can see in this graph, is actually quite low compared with that in other rich countries. Since minimum wages are set in national currency—

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). *The Canadian minimum wage varies by province from C$9.95 to C$11.00.