What Factors Determine the Price Elasticity of Demand?

Investors in private ambulance companies believe that the price elasticity of demand for an ambulance ride is low for two important reasons. First, in many if not most cases, an ambulance ride is a medical necessity. Second, in an emergency there really is no substitute for the standard of care that an ambulance provides. And even among ambulances there are typically no substitutes because in any given geographical area there is usually only one ambulance provider. (The exceptions are very densely populated areas, but even in those locations an ambulance dispatcher is unlikely to give you a choice of ambulance providers with an accompanying price list.)

In general there are four main factors that determine elasticity: whether a good is a necessity or luxury, the availability of close substitutes, the share of income a consumer spends on the good, and how much time has elapsed since a change in price. We’ll briefly examine each of these factors.

Whether the Good Is a Necessity or a Luxury As our opening story illustrates, the price elasticity of demand tends to be low if a good is something you must have, like a life-

The Availability of Close Substitutes As we just noted, the price elasticity of demand tends to be low if there are no close substitutes or if they are very difficult to obtain. In contrast, the price elasticity of demand tends to be high if there are other readily available goods that consumers regard as similar and would be willing to consume instead. For example, most consumers believe that there are fairly close substitutes to their favorite brand of breakfast cereal. As a result, if the maker of a particular brand of breakfast cereal raised the price significantly, that maker is likely to lose much—

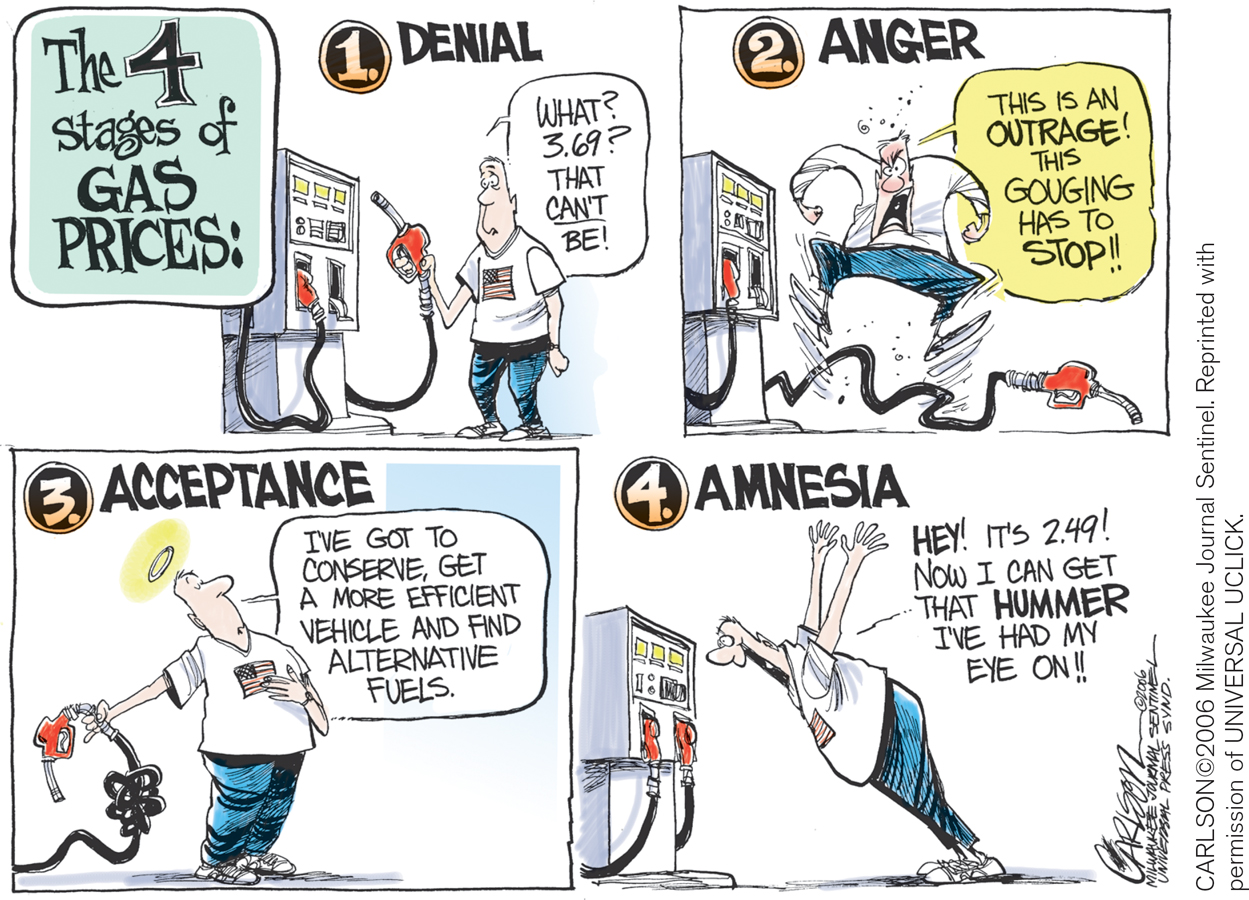

Share of Income Spent on the Good Consider a good that some people consume frequently, such as gasoline—

Time Elapsed Since Price Change In general, the price elasticity of demand tends to increase as consumers have more time to adjust. This means that the long-

A good illustration is the changes in Americans’ behavior over the past decade in response to higher gasoline prices. In 1998, a gallon of gasoline was only about $1. Over the years, however, gasoline prices steadily rose, so that by 2014 a gallon of gas cost from $3.50 to $4.00 in much of the United States. Over time, however, people changed their habits and choices in ways that enabled them to gradually reduce their gasoline consumption. In a recent survey, 53% of responders said they had made major life changes in order to cope with higher gas prices—

ECONOMICS in Action: Responding to Your Tuition Bill

Responding to Your Tuition Bill

College costs more than ever—

A 1988 study found that a 3% increase in tuition led to an approximately 2% fall in the number of students enrolled at four-

A 1999 study confirmed this pattern. In comparison to four-

In response to decreased state funding, many public colleges and universities have been experimenting with changes to their tuition schedule in order to increase revenue. A 2012 study found that in-

Not surprisingly, many public colleges and universities have found that raising the tuition for enrollments of out-

Quick Review

Demand is perfectly inelastic if it is completely unresponsive to price. It is perfectly elastic if it is infinitely responsive to price.

Demand is elastic if the price elasticity of demand is greater than 1. It is inelastic if the price elasticity of demand is less than 1. It is unit-

elastic if the price elasticity of demand is exactly 1. When demand is elastic, the quantity effect of a price increase dominates the price effect and total revenue falls. When demand is inelastic, the quantity effect is dominated by the price effect and total revenue rises.

Because the price elasticity of demand can change along the demand curve, economists refer to a particular point on the demand curve when speaking of “the” price elasticity of demand.

Ready availability of close substitutes makes demand for a good more elastic, as does a longer length of time elapsed since the price change. Demand for a necessity is less elastic, and demand for a luxury good is more elastic. Demand tends to be inelastic for goods that absorb a small share of a consumer’s income and elastic for goods that absorb a large share of income.

6-2

Question 6.4

For each case, choose the condition that characterizes demand: elastic demand, inelastic demand, or unit-

elastic demand. Total revenue decreases when price increases.

The additional revenue generated by an increase in quantity sold is exactly offset by revenue lost from the fall in price received per unit.

Total revenue falls when output increases.

Producers in an industry find they can increase their total revenues by coordinating a reduction in industry output.

Question 6.5

For the following goods, what is the elasticity of demand? Explain. What is the shape of the demand curve?

Demand for a blood transfusion by an accident victim

Demand by students for green erasers

Solutions appear at back of book.