Tax Rates and Revenue

A tax rate is the amount of tax people are required to pay per unit of whatever is being taxed.

In Figure 7-6, $40 per room is the tax rate on hotel rooms. A tax rate is the amount of tax levied per unit of whatever is being taxed. Sometimes tax rates are defined in terms of dollar amounts per unit of a good or service; for example, $2.46 per pack of cigarettes sold. In other cases, they are defined as a percentage of the price; for example, the payroll tax is 15.3% of a worker’s earnings up to $117,000.

There’s obviously a relationship between tax rates and revenue. That relationship is not, however, one-

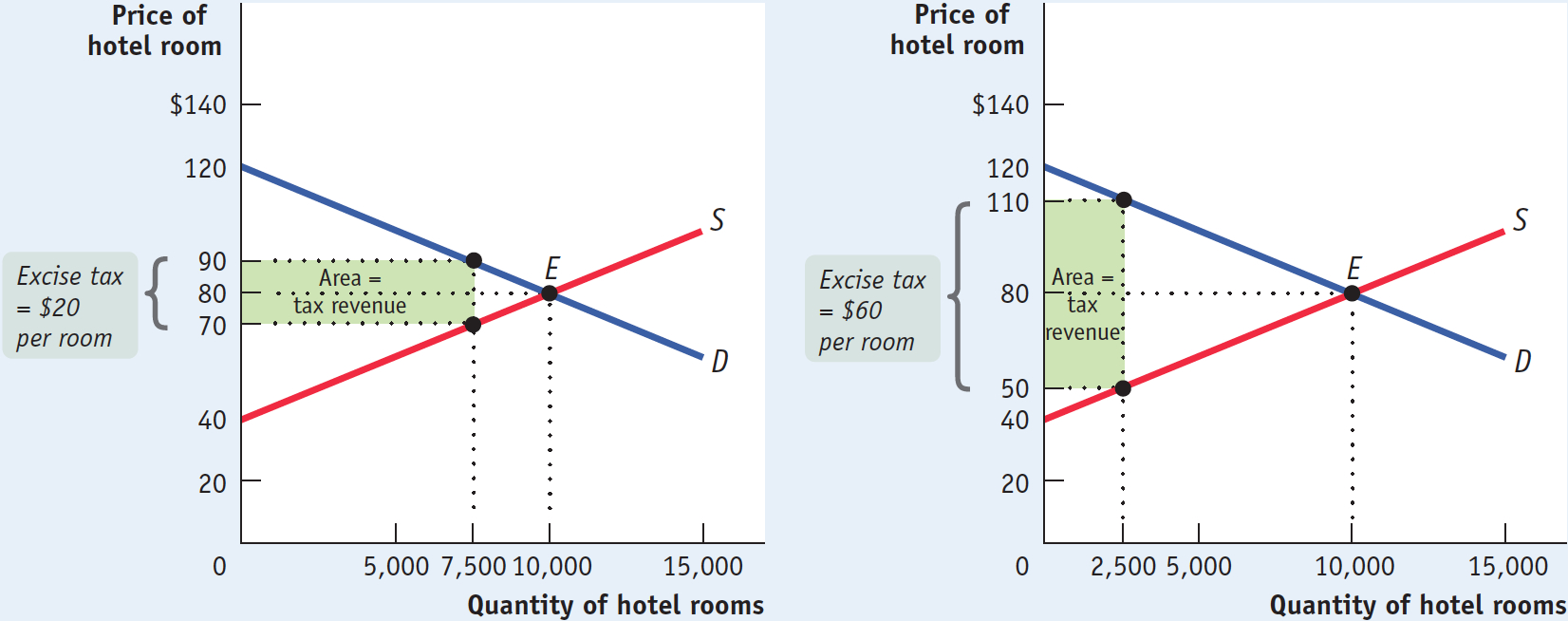

We can illustrate these points using our hotel room example. Figure 7-6 showed the revenue the government collects from a $40 tax on hotel rooms. Figure 7-7 shows the revenue the government would collect from two alternative tax rates—

Panel (a) of Figure 7-7 shows the case of a $20 tax, equal to half the tax rate illustrated in Figure 7-6. At this lower tax rate, 7,500 rooms are rented, generating tax revenue of:

Tax revenue = $20 per room × 7,500 rooms = $150,000

Recall that the tax revenue collected from a $40 tax rate is $200,000. So the revenue collected from a $20 tax rate, $150,000, is only 75% of the amount collected when the tax rate is twice as high ($150,000/$200,000 × 100 = 75%). To put it another way, a 100% increase in the tax rate from $20 to $40 per room leads to only a one-

Panel (b) depicts what happens if the tax rate is raised from $40 to $60 per room, leading to a fall in the number of rooms rented from 5,000 to 2,500. The revenue collected at a $60 per room tax rate is:

Tax revenue = $60 per room × 2,500 rooms = $150,000

This is also less than the revenue collected by a $40 per room tax. So raising the tax rate from $40 to $60 actually reduces revenue. More precisely, in this case raising the tax rate by 50% (($60 − $40)/$40 × 100 = 50%) lowers the tax revenue by 25% (($150,000 − $200,000)/$200,000 × 100 = −25%). Why did this happen? Because the fall in tax revenue caused by the reduction in the number of rooms rented more than offset the increase in the tax revenue caused by the rise in the tax rate. In other words, setting a tax rate so high that it deters a significant number of transactions will likely lead to a fall in tax revenue.

One way to think about the revenue effect of increasing an excise tax is that the tax increase affects tax revenue in two ways. On one side, the tax increase means that the government raises more revenue for each unit of the good sold, which other things equal would lead to a rise in tax revenue. On the other side, the tax increase reduces the quantity of sales, which other things equal would lead to a fall in tax revenue. The end result depends both on the price elasticities of supply and demand and on the initial level of the tax.

If the price elasticities of both supply and demand are low, the tax increase won’t reduce the quantity of the good sold very much, so tax revenue will definitely rise. If the price elasticities are high, the result is less certain; if they are high enough, the tax reduces the quantity sold so much that tax revenue falls. Also, if the initial tax rate is low, the government doesn’t lose much revenue from the decline in the quantity of the good sold, so the tax increase will definitely increase tax revenue. If the initial tax rate is high, the result is again less certain. Tax revenue is likely to fall or rise very little from a tax increase only in cases where the price elasticities are high and there is already a high tax rate.

The possibility that a higher tax rate can reduce tax revenue, and the corresponding possibility that cutting taxes can increase tax revenue, is a basic principle of taxation that policy makers take into account when setting tax rates. That is, when considering a tax created for the purpose of raising revenue (in contrast to taxes created to discourage undesirable behavior, known as “sin taxes”), a well-

In the real world, however, policy makers aren’t always well informed, but they usually aren’t complete fools either. That’s why it’s very hard to find real-

!worldview! FOR INQUIRING MINDS: French Tax Rates and L’Arc Laffer

One afternoon in 1974, the American economist Arthur Laffer drew on a napkin a diagram that came to be known as the “Laffer curve.” According to this diagram, raising tax rates initially increases tax revenue, but beyond a certain level a continued rise in tax rates causes tax revenues to fall as people forgo economic activity. Correspondingly, a reduction in tax rates from that threshold results in an increase in economic activity as more people are willing to undertake economic transactions.

Although not a new idea, Laffer’s diagram captured the American political debate at the time. In 1981, newly elected President Ronald Reagan enacted tax cuts with the promise that they would pay for themselves—

Very few economists now believe that Reagan’s tax cuts actually increased government revenue because, on the whole, American tax rates were simply not high enough to provide a significant deterrent to economic activity. Yet there is a theoretical case that the Laffer curve does exist at high tax rate levels. And the case of the French tax hike appears to present a real-

A 1997 change to the French tax law significantly raised taxes on wealthy French citizens. Moreover, unlike in the United States, it is relatively easy for a French person to move to a neighboring country, such as Belgium or Switzerland, with much lower taxes on the wealthy. As a result, according to one estimate, by 2013, 200 to 250 billion euros in assets—

The matter exploded in a public fracas between French president, Francois Hollande, and France’s most celebrated actor, Gerard Depardieu, when Hollande announced a 75% tax rate on high earning French to breach a huge government deficit. Hollande was eventually forced to back down, but not before Depardieu had moved just a few miles over the French border into Belgium.