Grammar as Rhetoric and Style

Cumulative, Periodic, and Inverted Sentences

Most of the time, writers of English use the following standard sentence patterns:

Subject/Verb (SV)

My father cried.—Terry Tempest Williams

Subject/Verb/Subject complement (SVC)

Even the streams were now lifeless.—Rachel Carson

Subject/Verb/Direct object (SVO)

We believed her.—Terry Tempest Williams

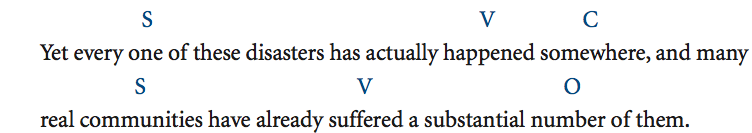

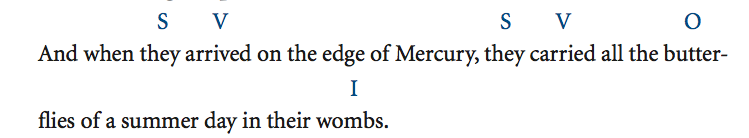

To make longer sentences, writers often coordinate two or more of the standard sentence patterns or subordinate one sentence pattern to another. (See the grammar lesson about subordination on p. 1124.) Here are examples of both techniques.

Coordinating patterns

—Rachel Carson

Subordinating one pattern to another

—Terry Tempest Williams

The downside to sticking with standard sentence patterns, coordinating them, or subordinating them is that too many standard sentences in a row become monotonous. So writers break out of the standard patterns now and then by using a more unusual pattern, such as the cumulative sentence, the periodic sentence, or the inverted sentence.

When you use one of these sentence patterns, you call attention to that sentence because its pattern contrasts significantly with the pattern of the sentences surrounding it. You can use unusual sentence patterns to emphasize a point, as well as to control sentence rhythm, increase tension, or create a dramatic impact. In other words, using the unusual pattern helps you avoid monotony in your writing.

Cumulative Sentence

The cumulative, or so-called loose, sentence begins with a standard sentence pattern (shown here in blue) and adds multiple details after it. The details can take the form of subordinate clauses or different kinds of phrases. These details accumulate, or pile up—hence, the name cumulative.

The women moved through the streets as winged messengers, twirling around each other in slow motion, peeking inside homes and watching the easy sleep of men and women.

—Terry Tempest Williams

Here’s another cumulative sentence, this one from Michael Pollan.

Venture farther, though, and you come to regions of the supermarket where the very notion of species seems increasingly obscure: the canyons of breakfast cereals and condiments; the freezer cases stacked with “home meal replacements” and bagged platonic peas; the broad expanses of soft drinks and towering cliffs of snacks; the unclassifiable Pop-Tarts and Lunchables; the frankly synthetic coffee whiteners and the Linnaeus-defying Twinkie.

Look closely at this cumulative sentence by Lewis Thomas:

We have grown into everywhere, spreading like a new growth over the entire surface, touching and affecting every other kind of life, incorporating ourselves.

The independent clause in the sentence focuses on the growth of humanity. Then the sentence accumulates a string of modifiers about the extent of that growth. Using a cumulative sentence allows Thomas to include all of these modifiers in one smooth sentence, rather than using a series of shorter sentences that repeat grown. Furthermore, this accumulation of modifiers takes the reader into the scene just as the writer experiences it, one detail at a time.

Periodic Sentence

The periodic sentence begins with multiple details and holds off a standard sentence pattern—or at least its predicate (shown here in blue)—until the end. The following periodic sentence by Lewis Thomas presents its subject, human beings, followed by an accumulation of modifiers, with the predicate coming at the end.

Human beings, large terrestrial metazoans, fired by energy from microbial symbionts lodged in their cells, instructed by tapes of nucleic acid stretching back to the earliest live membranes, informed by neurons essentially the same as all the other neurons on earth, sharing structures with mastodons and lichens, living off the sun, are now in charge, running the place, for better or worse.

In the following periodic sentence, Ralph Waldo Emerson packs the front of the sentence with phrases providing elaborate detail:

Crossing a bare common, in snow puddles, at twilight, under a clouded sky, without having in my thoughts any occurrence of special good fortune, I have enjoyed a perfect exhilaration.

The vivid descriptions engage us, so that by the end of the sentence we can feel (or at least imagine) the exhilaration Emerson feels. By placing the descriptions at the beginning of the sentence, Emerson demonstrates how nature can ascend from the physical (“snow puddles,” “clouded sky”) to the psychological (“without . . . thoughts of . . . good fortune”), and finally to the spiritual (“perfect exhilaration”).

Could Emerson have written this as a cumulative sentence? He probably could have by moving things around—“I have enjoyed a perfect exhilaration as I was crossing . . .”—and then providing the details. In some ways, the impact of the descriptive detail would be similar.

Whether you choose to place detail at the beginning or end of a sentence often depends on the surrounding sentences. Unless you have a good reason, though, you probably should not put one cumulative sentence after another or one periodic sentence after another. Instead, by shifting sentence patterns, you can vary sentence length and change the rhythm of your sentences.

Finally, perhaps the most famous example of the periodic sentence in modern English prose is the fourth sentence in paragraph 14 of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” (p. 280):

But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick, and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five-year-old son who is asking, “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?”; when you take a cross-country drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “colored”; when your first name becomes “nigger,” your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and your wife and mother are never given the respected title “Mrs.”; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness”—then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.

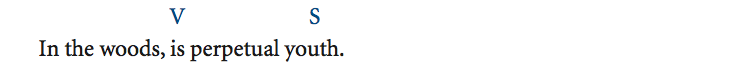

Inverted Sentence

In every standard English sentence pattern, the subject comes before the verb (SV). But if a writer chooses, he or she can invert the standard sentence pattern and put the verb before the subject (VS). This is called an inverted sentence. Here is an example:

Everywhere was a shadow of death.—Rachel Carson

Controlled exponential growth is what you’d really like to see.—Joy Williams

What’s at stake as they busy themselves are your tax dollars and mine, and ultimately our freedom too.—E. O. Wilson

The inverted sentence pattern slows the reader down, because it is simply more difficult to comprehend inverted word order. Take this example from Emerson’s “Nature”:

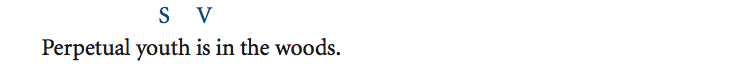

In this example, Emerson calls attention to “woods” and “youth,” minimizing the verb “is” and juxtaposing a place (“woods”) with a state of being (“youth”). Consider the difference if he had written:

This “revised” version is easier to read quickly, and even though the meaning is essentially the same, the emphasis is different. In fact, to understand the full impact, we need to consider the sentence in its context. If you look back at Emerson’s essay “Nature,” you’ll see that his sentence is a short one among longer, more complex sentences. That combination of inversion and contrasting length makes the sentence—and the idea it conveys—stand out.

A Word about Punctuation

It is important to follow the normal rules of comma usage when punctuating unusual sentence patterns. In a cumulative sentence, the descriptors that follow the main clause need to be set off from it and from one another with commas, as in the example from Terry Tempest Williams on page 927. Likewise, in a periodic sentence, the series of clauses or phrases that precede the subject should be set off from the subject and from one another by commas, as in the Emerson example on page 897. When writing an inverted sentence, you may be tempted to insert a comma between the verb and the subject because of the unusual order—but don’t.