Annotating

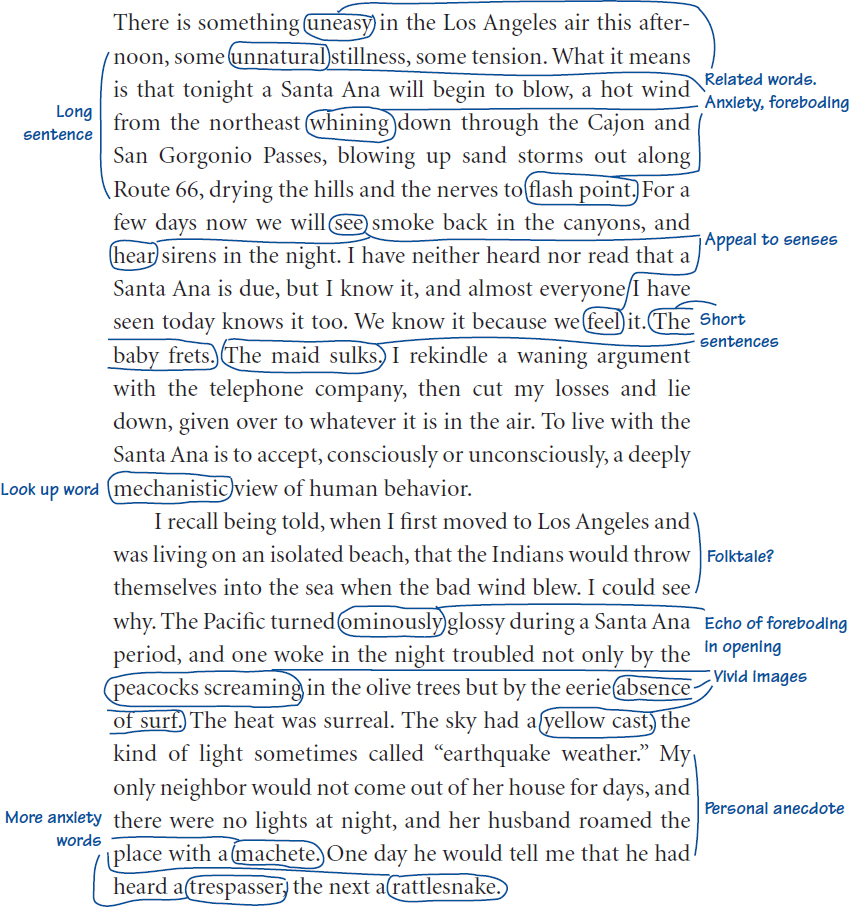

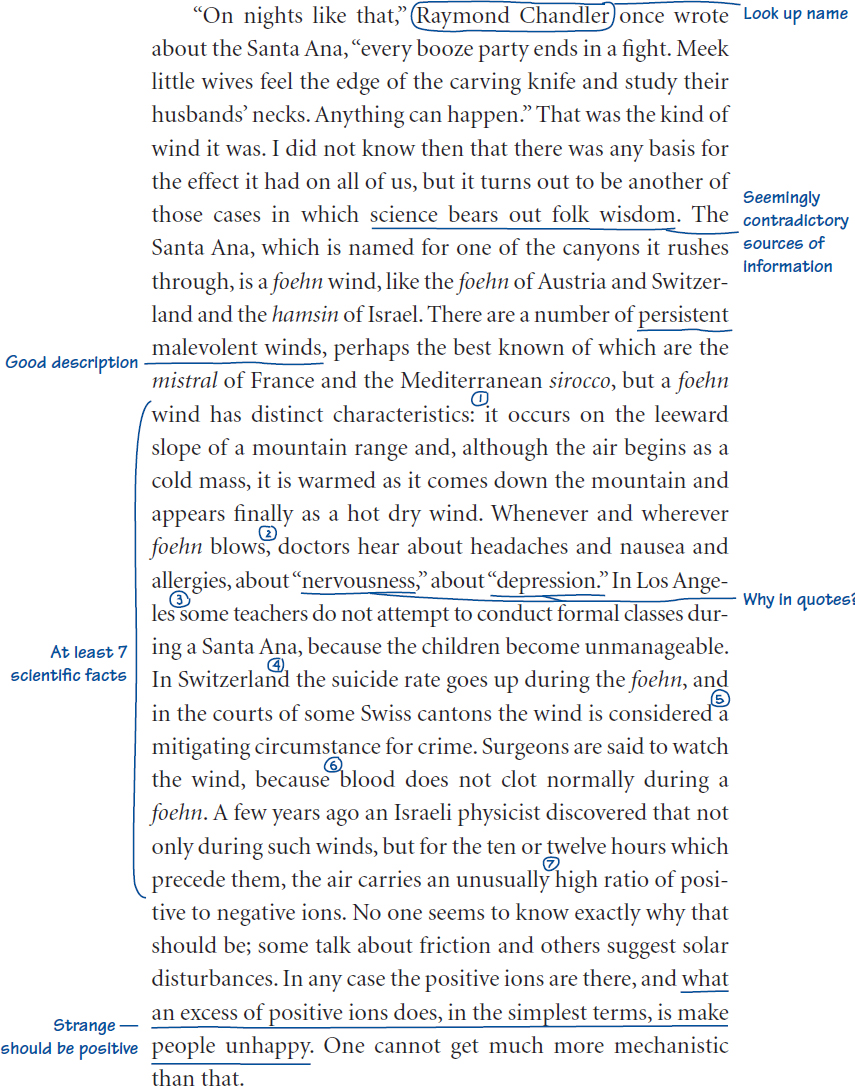

Another close reading technique you can use is annotation. Annotating a text requires reading with a pencil in hand. If you are not allowed to write in your book, then write on sticky notes. As you read, circle words you don’t know, or write them on the sticky notes. Identify main ideas—thesis statements, topic sentences—and also words, phrases, or sentences that appeal to you, that seem important, or that you don’t understand. Look for figures of speech such as metaphors, similes, and personification—as well as imagery and striking detail. If you don’t know the technical term for something, just describe it. For example, if you come across an adjective-and-noun combination that seems contradictory, such as “meager abundance,” and you don’t know that the term for it is oxymoron, you might still note the juxtaposition of two words that have opposite meanings. Ask questions or comment on what you have read. In short, as you read, listen to the voice in your head, and write down what that voice is saying.

Let’s try out this approach using a passage by Joan Didion about California’s Santa Ana winds from her 1965 essay “Los Angeles Notebook.” Read the passage first, and see if you can come up with some ideas about Didion’s purpose. Then we will look closely at the choices she makes and the effects of those choices.

The Santa Ana Winds

Joan Didion

There is something uneasy in the Los Angeles air this afternoon, some unnatural stillness, some tension. What it means is that tonight a Santa Ana will begin to blow, a hot wind from the northeast whining down through the Cajon and San Gorgonio Passes, blowing up sand storms out along Route 66, drying the hills and the nerves to flash point. For a few days now we will see smoke back in the canyons, and hear sirens in the night. I have neither heard nor read that a Santa Ana is due, but I know it, and almost everyone I have seen today knows it too. We know it because we feel it. The baby frets. The maid sulks. I rekindle a waning argument with the telephone company, then cut my losses and lie down, given over to whatever it is in the air. To live with the Santa Ana is to accept, consciously or unconsciously, a deeply mechanistic view of human behavior.

I recall being told, when I first moved to Los Angeles and was living on an isolated beach, that the Indians would throw themselves into the sea when the bad wind blew. I could see why. The Pacific turned ominously glossy during a Santa Ana period, and one woke in the night troubled not only by the peacocks screaming in the olive trees but by the eerie absence of surf. The heat was surreal. The sky had a yellow cast, the kind of light sometimes called “earthquake weather.” My only neighbor would not come out of her house for days, and there were no lights at night, and her husband roamed the place with a machete. One day he would tell me that he had heard a trespasser, the next a rattlesnake.

“On nights like that,” Raymond Chandler once wrote about the Santa Ana, “every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ necks. Anything can happen.” That was the kind of wind it was. I did not know then that there was any basis for the effect it had on all of us, but it turns out to be another of those cases in which science bears out folk wisdom. The Santa Ana, which is named for one of the canyons it rushes through, is a foehn wind, like the foehn of Austria and Switzerland and the hamsin of Israel. There are a number of persistent malevolent winds, perhaps the best known of which are the mistral of France and the Mediterranean sirocco, but a foehn wind has distinct characteristics: it occurs on the leeward slope of a mountain range and, although the air begins as a cold mass, it is warmed as it comes down the mountain and appears finally as a hot dry wind. Whenever and wherever foehn blows, doctors hear about headaches and nausea and allergies, about “nervousness,” about “depression.” In Los Angeles some teachers do not attempt to conduct formal classes during a Santa Ana, because the children become unmanageable. In Switzerland the suicide rate goes up during the foehn, and in the courts of some Swiss cantons the wind is considered a mitigating circumstance for crime. Surgeons are said to watch the wind, because blood does not clot normally during a foehn. A few years ago an Israeli physicist discovered that not only during such winds, but for the ten or twelve hours which precede them, the air carries an unusually high ratio of positive to negative ions. No one seems to know exactly why that should be; some talk about friction and others suggest solar disturbances. In any case the positive ions are there, and what an excess of positive ions does, in the simplest terms, is make people unhappy. One cannot get much more mechanistic than that.

You probably noticed that while Didion seems to be writing about a natural phenomenon—the Santa Ana winds—she is also commenting on human nature and the way nature affects human behavior. Her purpose, then, is social commentary as much as the observation of an event in nature. In addition, you may notice on a second or third reading that her tone gives you another message: the way Didion sees human nature.

Following is an annotated version of the Didion passage: