The Classical Oration

Classical rhetoricians outlined a five-part structure for an oratory, or speech, that writers still use today, although perhaps not always consciously:

- The introduction (exordium) introduces the reader to the subject under discussion. In Latin, exordium means “beginning a web,” which is an apt description for an introduction. Whether it is a single paragraph or several, the introduction draws the readers into the text by piquing their interest, challenging them, or otherwise getting their attention. Often the introduction is where the writer establishes ethos.

- The narration (narratio) provides factual information and background material on the subject at hand, thus beginning the developmental paragraphs, or establishes why the subject is a problem that needs addressing. The level of detail a writer uses in this section depends largely on the audience’s knowledge of the subject. Although classical rhetoric describes narration as appealing to logos, in actuality it often appeals to pathos because the writer attempts to evoke an emotional response about the importance of the issue being discussed.

- The confirmation (confirmatio), usually the major part of the text, includes the development or the proof needed to make the writer’s case—the nuts and bolts of the essay, containing the most specific and concrete detail in the text. The confirmation generally makes the strongest appeal to logos.

- The refutation (refutatio), which addresses the counterargument, is in many ways a bridge between the writer’s proof and conclusion. Although classical rhetoricians recommended placing this section at the end of the text as a way to anticipate objections to the proof given in the confirmation section, this is not a hard-and-fast rule. If opposing views are well known or valued by the audience, a writer will address them before presenting his or her own argument. The counterargument’s appeal is largely to logos.

- The conclusion (peroratio)—whether it is one paragraph or several—brings the essay to a satisfying close. Here the writer usually appeals to pathos and reminds the reader of the ethos established earlier. Rather than simply repeating what has gone before, the conclusion brings all the writer’s ideas together and answers the question, so what? Writers should remember the classical rhetoricians’ advice that the last words and ideas of a text are those the audience is most likely to remember.

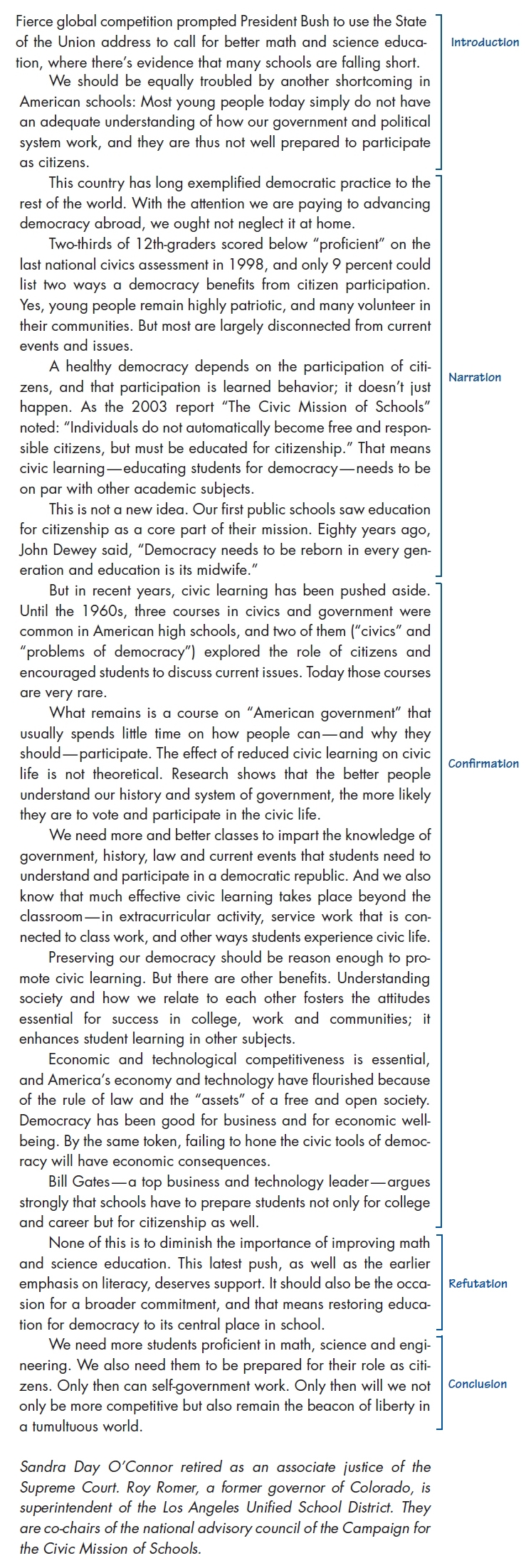

An example of the classical model at work is the piece below written in 2006 by Sandra Day O’Connor, a former Supreme Court justice, and Roy Romer, then superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District.

Not by Math Alone

Sandra Day O’connor and Roy Romer

Sandra Day O’Connor and Roy Romer follow the classical model very closely. The opening two paragraphs are an introduction to the main idea the authors develop. In fact, the last sentence of paragraph 2 is their two-part claim, or thesis: “Most young people today simply do not have an adequate understanding of how our government and political system work, and they are thus not well prepared to participate as citizens.” O’Connor’s position as a former Supreme Court justice establishes her ethos as a reasonable person, an advocate for justice, and a concerned citizen. Romer’s biographical note at the end of the article suggests similar qualities. The authors use the pronoun “we” in the article to refer not only to themselves but to all of “us” who are concerned about American society. The opening phrase, “Fierce global competition,” connotes a sense of urgency, and the warning that we are not adequately preparing our young people to participate as citizens is sure to evoke an emotional response of concern, even alarm.

In paragraphs 3 to 6—the narration—the authors provide background information, including facts that add urgency to their point. They cite statistics, quote from research reports, even call on the well-known educator John Dewey. They also include a definition of “civic learning,” a key term in their argument. Their facts-and-figures appeal is largely to logos, though the language of “a healthy democracy” certainly engages the emotions.

Paragraphs 7 to 12 present the bulk of the argument—the confirmation—by offering reasons and examples to support the case that young people lack the knowledge necessary to be informed citizens. The authors link civic learning to other subjects as well as to economic development. They quote Bill Gates, chairman of Microsoft, who has spoken about the economic importance of a well-informed citizenry.

In paragraph 13, O’Connor and Romer briefly address a major objection—the refutation—that we need to worry more about math and science education than about civic learning. While they concede the importance of math, science, and literacy, they point out that it is possible to increase civic education without undermining the gains made in those other fields.

The final paragraph—the conclusion—emphasizes the importance of a democracy to a well-versed citizenry, a point that stresses the shared values of the authors with their audience. The appeal to pathos is primarily through the vivid language, particularly the final sentence with its emotionally charged description “beacon of liberty,” a view of their nation that most Americans hold dear.