Health and Happiness

Robert D. Putnam

Robert D. Putnam (b. 1941) is the Peter and Isabel Malkin Professor of Public Policy at Harvard University, former dean of the John F. Kennedy School of Government, and founder of the Saguaro Seminar, a program dedicated to fostering civic engagement in America. He received his undergraduate degree from Swarthmore College, won a Fulbright Fellowship to Balliol College at Oxford University, and received both his MA and PhD from Yale University. He was the 2006 recipient of the Skytte Prize, the most prestigious international award for scholarly achievement in political science. Among the ten books Putnam has authored or co-authored, three are considered his most influential: Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (1995), Better Together: Restoring the American Community (2003), and American Grace (2010), a study of religion and public life. Bowling Alone argues that civic, social, associational, and political connections—what is called “social capital”—have decreased dramatically during the latter half of the twentieth century. Following is a chapter analyzing the impact of social connectedness on physical and psychological health. Based on extensive research, this enormously popular book introduced a wide audience to Putnam’s groundbreaking ideas.

Of all the domains in which I have traced the consequences of social capital, in none is the importance of social connectedness so well established as in the case of health and well-being. Scientific studies of the effects of social cohesion on physical and mental health can be traced to the seminal work of the nineteenth-century sociologist Émile Durkheim, Suicide. Self-destruction is not merely a personal tragedy, he found, but a sociologically predictable consequence of the degree to which one is integrated into society—rarer among married people, rarer in more tightly knit religious communities, rarer in times of national unity, and more frequent when rapid social change disrupts the social fabric. Social connectedness matters to our lives in the most profound way.

In recent decades public health researchers have extended this initial insight to virtually all aspects of health, physical as well as psychological. Dozens of painstaking studies from Alameda (California) to Tecumseh (Michigan) have established beyond reasonable doubt that social connectedness is one of the most powerful determinants of our well-being. The more integrated we are with our community, the less likely we are to experience colds, heart attacks, strokes, cancer, depression, and premature death of all sorts. Such protective effects have been confirmed for close family ties, for friendship networks, for participation in social events, and even for simple affiliation with religious and other civic associations. In other words, both machers* and schmoozers enjoy these remarkable health benefits.

After reviewing dozens of scientific studies, sociologist James House and his colleagues have concluded that the positive contributions to health made by social integration and social support rival in strength the detrimental contributions of well-established biomedical risk factors like cigarette smoking, obesity, elevated blood pressure, and physical inactivity. Statistically speaking, the evidence for the health consequences of social connectedness is as strong today as was the evidence for the health consequences of smoking at the time of the first surgeon general’s report on smoking. If the trends in social disconnection are as pervasive as I argued in section II, then “bowling alone” represents one of the nation’s most serious public health challenges.1

Although researchers aren’t entirely sure why social cohesion matters for health, they have a number of plausible theories. First, social networks furnish tangible assistance, such as money, convalescent care, and transportation, which reduces psychic and physical stress and provides a safety net. If you go to church regularly, and then you slip in the bathtub and miss a Sunday, someone is more likely to notice. Social networks also may reinforce healthy norms—socially isolated people are more likely to smoke, drink, overeat, and engage in other health-damaging behaviors. And socially cohesive communities are best able to organize politically to ensure first-rate medical services.2

5

Finally, and most intriguingly, social capital might actually serve as a physiological triggering mechanism, stimulating people’s immune systems to fight disease and buffer stress. Research now under way suggests that social isolation has measurable biochemical effects on the body. Animals who have been isolated develop more extensive atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) than less isolated animals, and among both animals and humans loneliness appears to decrease the immune response and increase blood pressure. Lisa Berkman, one of the leading researchers in the field, has speculated that social isolation is “a chronically stressful condition to which the organism respond[s] by aging faster.”3

Some studies have documented the strong correlation between connectedness and health at the community level. Others have zeroed in on individuals, both in natural settings and in experimental conditions. These studies are for the most part careful to account for confounding factors—the panoply of other physiological, economic, institutional, behavioral, and demographic forces that might also affect an individual’s health. In many cases these studies are longitudinal: they check on people over many years to get a better understanding of what lifestyle changes might have caused people’s health to improve or decline. Thus researchers have been able to show that social isolation precedes illness to rule out the possibility that the isolation was caused by illness. Over the last twenty years more than a dozen large studies of this sort in the United States, Scandinavia, and Japan have shown that people who are socially disconnected are between two and five times more likely to die from all causes, compared with matched individuals who have close ties with family, friends, and the community.4

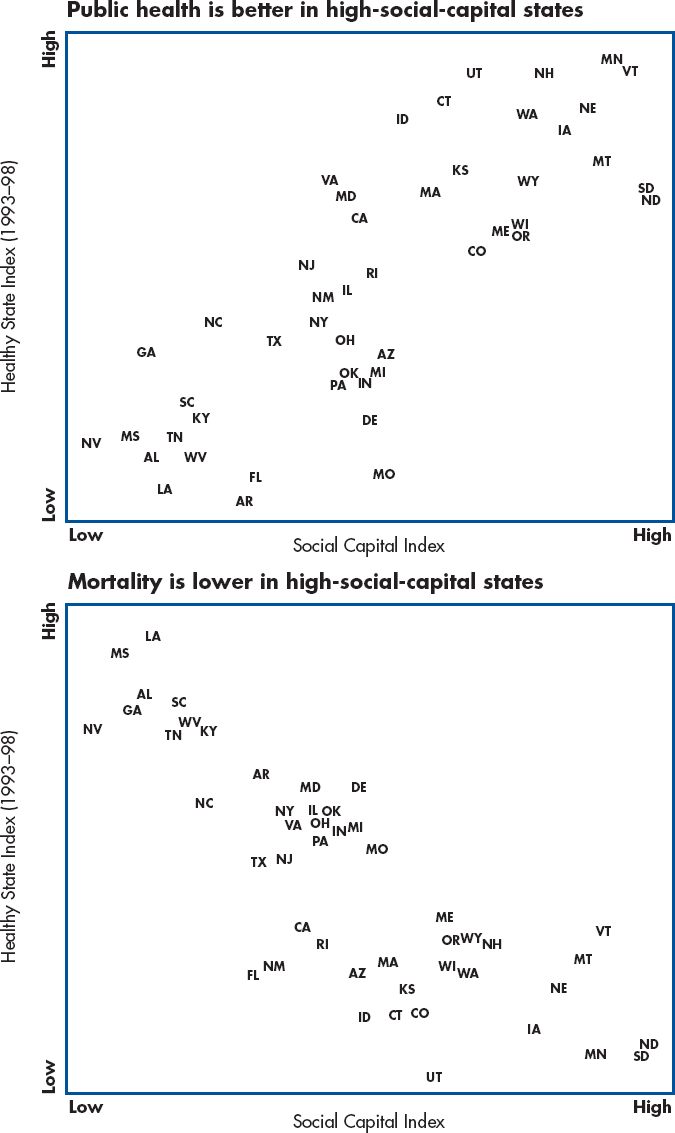

A recent study by researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health provides an excellent overview of the link between social capital and physical health across the United States.5 Using survey data from nearly 170,000 individuals in all fifty states, these researchers found, as expected, that people who are African American, lack health insurance, are overweight, smoke, have a low income, or lack a college education are at greater risk for illness than are more socioeconomically advantaged individuals. But these researchers also found an astonishingly strong relationship between poor health and low social capital. States whose residents were most likely to report fair or poor health were the same states in which residents were most likely to distrust others.6 Moving from a state with a wealth of social capital to a state with very little social capital (low trust, low voluntary group membership) increased one’s chances of poor to middling health by roughly 40–70 percent. When the researchers accounted for individual residents’ risk factors, the relationship between social capital and individual health remained. Indeed, the researchers concluded that if one wanted to improve one’s health, moving to a high-social-capital state would do almost as much good as quitting smoking. These authors’ conclusion is complemented by our own analysis. We found a strong positive relationship between a comprehensive index of public health and the Social Capital Index, along with a strong negative correlation between the Social Capital Index and all-cause mortality rates.7 (See table 1 for the measure of public health and health care and figure 1 for the correlations of public health and mortality with social capital.)

TABLE 1: WHICH STATE HAS THE BEST HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE?

| MORGAN-QUITNO HEALTHIEST STATE RANKINGS (1993–1998): |

| 1. Births of low birth weight as a percent of all births (–) |

| 2. Births to teenage mothers as a percent of live births (–) |

| 3. Percent of mothers receiving late or no prenatal care (–) |

| 4. Death rate (–) |

| 5. Infant mortality rate (–) |

| 6. Estimated age adjusted death rate by cancer (–) |

| 7. Death rate by suicide (–) |

| 8. Percent of population not covered by health insurance (–) |

| 9. Change in percent of population uninsured (–) |

| 10. Health care expenditures as a percent of gross state product (–) |

| 11. Per capita personal health expenditures (–) |

| 12. Estimate rate of new cancer cases (–) |

| 13. AIDS rate (–) |

| 14. Sexually transmitted disease rate (–) |

| 15. Percent of population lacking access to primary care (–) |

| 16. Percent of adults who are binge drinkers (–) |

| 17. Percent of adults who smoke (–) |

| 18. Percent of adults overweight (–) |

| 19. Days in past month when physical health was “not good” (–) |

| 20. Community hospitals per 1,000 square miles (+) |

| 21. Beds in community hospitals per 100,000 population (+) |

| 22. Percent of children aged 19–35 months fully immunized (+) |

| 23. Safety belt usage rate (+) |

The state-level findings are suggestive, but far more definitive evidence of the benefits of community cohesion is provided by a wealth of studies that examine individual health as a function of individual social-capital resources. Nowhere is the connection better illustrated than in Roseto, Pennsylvania.8 This small Italian American community has been the subject of nearly forty years of in-depth study, beginning in the 1950s when medical researchers noticed a happy but puzzling phenomenon. Compared with residents of neighboring towns, Rosetans just didn’t die of heart attacks. Their (age-adjusted) heart attack rate was less than half that of their neighbors; over a seven-year period not a single Roseto resident under forty-seven had died of a heart attack. The researchers looked for the usual explanations: diet, exercise, weight, smoking, genetic predisposition, and so forth. But none of these explanations held the answer—indeed, Rosetans were actually more likely to have some of these risk factors than were people in neighboring towns. The researchers then began to explore Roseto’s social dynamics. The town had been founded in the nineteenth century by people from the same southern Italian village. Through local leadership these immigrants had created a mutual aid society, churches, sports clubs, a labor union, a newspaper, Scout troops, and a park and athletic field. The residents had also developed a tight-knit community where conspicuous displays of wealth were scorned and family values and good behaviors reinforced. Rosetans learned to draw on one another for financial, emotional, and other forms of support. By day they congregated on front porches to watch the comings and goings, and by night they gravitated to local social clubs. In the 1960s the researchers began to suspect that social capital (though they didn’t use the term) was the key to Rosetans’ healthy hearts. And the researchers worried that as socially mobile young people began to reject the tight-knit Italian folkways, the heart attack rate would begin to rise. Sure enough, by the 1980s Roseto’s new generation of adults had a heart attack rate above that of their neighbors in a nearby and demographically similar town.

The Roseto story is a particularly vivid and compelling one, but numerous other studies have supported the medical researchers’ intuition that social cohesion matters, not just in preventing premature death, but also in preventing disease and speeding recovery. For example, a long-term study in California found that people with the fewest social ties have the highest risk of dying from heart disease, circulatory problems, and cancer (in women), even after accounting for individual health status, socioeconomic factors, and use of preventive health care.9 Other studies have linked lower death rates with membership in voluntary groups and engagement in cultural activities;10 church attendance;11 phone calls and visits with friends and relatives;12 and general sociability such as holding parties at home, attending union meetings, visiting friends, participating in organized sports, or being members of highly cohesive military units.13 The connection with social capital persisted even when the studies examined other factors that might influence mortality, such as social class, race, gender, smoking and drinking, obesity, lack of exercise, and (significantly) health problems. In other words, it is not simply that healthy, health-conscious, privileged people (who might happen also to be more socially engaged) tend to live longer. The broad range of illnesses shown to be affected by social support and the fact that the link is even tighter with death than with sickness tend to suggest that the effect operates at a quite fundamental level of general bodily resistance. What these studies tell us is that social engagement actually has an independent influence on how long we live.

10

Social networks help you stay healthy. The finding by a team of researchers at Carnegie Mellon University that people with more diverse social ties get fewer colds is by no means unique.14 For example, stroke victims who had strong support networks functioned better after the stroke, and recovered more physical capacities, than did stroke victims with thin social networks.15 Older people who are involved with clubs, volunteer work, and local politics consider themselves to be in better general health than do uninvolved people, even after accounting for socioeconomic status, demographics, level of medical care use, and years in retirement.16

The bottom line from this multitude of studies: As a rough rule of thumb, if you belong to no groups but decide to join one, you cut your risk of dying over the next year in half. If you smoke and belong to no groups, it’s a toss-up statistically whether you should stop smoking or start joining. These findings are in some ways heartening: it’s easier to join a group than to lose weight, exercise regularly, or quit smoking.

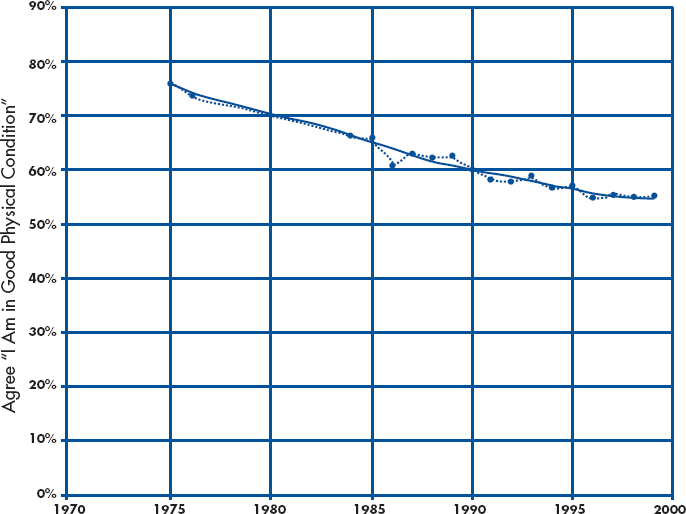

But the findings are sobering, too. As we saw in section II, there has been a general decline in social participation over the past twenty-five years. Figure 2 shows that this same period witnessed a significant decline in self-reported health, despite tremendous gains in medical diagnosis and treatment. Of course, by many objective measures, including life expectancy, Americans are healthier than ever before, but these self-reports indicate that we are feeling worse.17 These self-reports are in turn closely linked to social connectedness, in the sense that it is precisely less connected Americans who are feeling worse. These facts alone do not prove that we are suffering physically from our growing disconnectedness, but taken in conjunction with the more systematic evidence of the health effects of social capital, this evidence is another link in the argument that the erosion of social capital has measurable ill effects.

We observed in chapter 14 the remarkable coincidence that during the same years that social connectedness has been declining, depression and even suicide have been increasing. We also noted that this coincidence has deep generational roots, in the sense that the generations most disconnected socially also suffer most from what some public health experts call “Agent Blue.” In any given year 10 percent of Americans now suffer from major depression, and depression imposes the fourth largest total burden of any disease on Americans overall. Much research has shown that social connections inhibit depression. Low levels of social support directly predict depression, even controlling for other risk factors, and high levels of social support lessen the severity of symptoms and speed recovery. Social support buffers us from the stresses of daily life. Face-to-face ties seem to be more therapeutic than ties that are geographically distant. In short, even within the single domain of depression, we pay a very high price for our slackening social connectedness.18

Countless studies document the link between society and psyche: people who have close friends and confidants, friendly neighbors, and supportive co-workers are less likely to experience sadness, loneliness, low self-esteem, and problems with eating and sleeping. Married people are consistently happier than people who are unattached, all else being equal. These findings will hardly surprise most Americans, for in study after study people themselves report that good relationships with family members, friends, or romantic partners—far more than money or fame—are prerequisites for their happiness.19 The single most common finding from a half century’s research on the correlates of life satisfaction, not only in the United States but around the world, is that happiness is best predicted by the breadth and depth of one’s social connections.20

15

We can see how social capital ranks as a producer of warm, fuzzy feelings by examining a number of questions from the DDB Needham Life Style survey archives:

“I wish I could leave my present life and do something entirely different.”

“I am very satisfied with the way things are going in my life these days.”

“If I had my life to live over, I would sure do things differently.”

“I am much happier now than I ever was before.”

Responses to these items are strongly intercorrelated, so I combined them into a single index of happiness with life. Happiness in this sense is correlated with material well-being. Generally speaking, as one rises up the income hierarchy, life contentment increases. So money can buy happiness after all. But not as much as marriage. Controlling for education, age, gender, marital status, income, and civic engagement, the marginal “effect” of marriage on life contentment is equivalent to moving roughly seventy percentiles up the income hierarchy—say, from the fifteenth percentile to the eighty-fifty percentile.21 In round numbers, getting married is the “happiness equivalent” of quadrupling your annual income.22

What about education and contentment? Education has important indirect links to happiness through increased earning power, but controlling for income (as well as age, gender, and the rest), what is the marginal correlation of education itself with life satisfaction? In round numbers the answer is that four additional years of education—attending college, for example—is the “happiness equivalent” of roughly doubling your annual income.

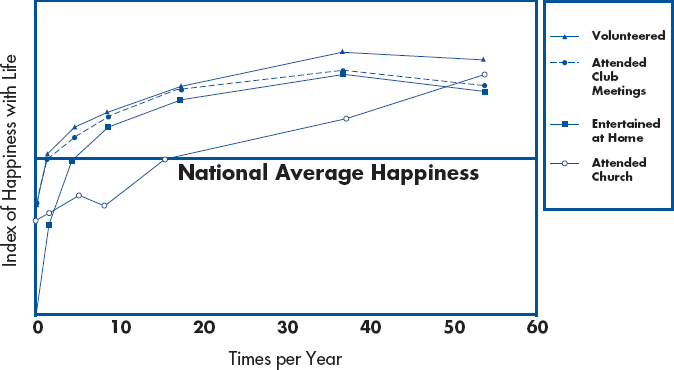

Having assessed in rough-and-ready terms the correlations of financial capital (income), human capital (education), and one form of social capital (marriage) with life contentment, we can now ask equivalent questions about the correlations between happiness and various forms of social interaction. Let us ask about regular club members (those who attend monthly), regular volunteers (those who do so monthly), people who entertain regularly at home (say, monthly), and regular (say, biweekly) churchgoers. The differences are astonishingly large. Regular club attendance, volunteering, entertaining, or church attendance is the happiness equivalent of getting a college degree or more than doubling your income. Civic connections rival marriage and affluence as predictors of life happiness.23

If monthly club meetings are good, are daily club meetings thirty times better? The answer is no. Figure 3 shows what economists might call the “declining marginal productivity” of social interaction with respect to happiness. The biggest happiness returns to volunteering, clubgoing, and entertaining at home appear to come between “never” and “once a month.” There is very little gain in happiness after about one club meeting (or party or volunteer effort) every three weeks. After fortnightly encounters, the marginal correlation of additional social interaction with happiness is actually negative—another finding that is consistent with common experience! Churchgoing, on the other hand, is somewhat different, in that at least up through weekly attendance, the more the merrier.

20

This analysis is, of course, phrased intentionally in round numbers, for the underlying calculations are rough and ready. Moreover the direction of causation remains ambiguous. Perhaps happy people are more likely than unhappy people to get married, win raises at work, continue in school, attend church, join clubs, host parties, and so on. My present purpose is merely to illustrate that social connections have profound links with psychological well-being. The Beatles got it right: we all “get by with a little help from our friends.”

In the decades since the Fab Four topped the charts, life satisfaction among adult Americans has declined steadily. Roughly half the decline in contentment is associated with financial worries, and half is associated with declines in social capital: lower marriage rates and decreasing connectedness to friends and community. Not all segments of the population are equally gloomy. Survey data show that the slump has been greatest among young and middle-aged adults (twenty to fifty-five). People over fifty-five—our familiar friends from the long civic generation—are actually happier than were people their age a generation ago.24

Some of the generational discrepancy is due to money worries: despite rising prosperity, young and middle-aged people feel less secure financially. But some of the disparity is also due to social connectedness. Young and middle-aged adults today are simply less likely to have friends over, attend church, or go to club meetings than were earlier generations. Psychologist Martin Seligman argues that more of us are feeling down because modern society encourages a belief in personal control and autonomy more than a commitment to duty and common enterprise. This transformation heightens our expectations about what we can achieve through choice and grit and leaves us unprepared to deal with life’s inevitable failures. Where once we could fall back on social capital—families, churches, friends—these no longer are strong enough to cushion our fall.25 In our personal lives as well as in our collective life, the evidence of this chapter suggests, we are paying a significant price for a quarter century’s disengagement from one another.

Notes

- For comprehensive overviews of the massive literature on health and social connectedness, see James S. House, Karl R. Landis, and Debra Umberson, “Social Relationships and Health,” Science 241 (1988): 540–545; Lisa F. Berkman, “The Role of Social Relations in Health Promotion,” Psychosomatic Medicine 57 (1995): 245–254; and Teresa E. Seeman, “Social Ties and Health: The Benefits of Social Integration,” Annual of Epidemiology 6 (1996): 442–451. Other useful recent overviews include Benjamin C. Amick III, Sol Levine, Alvin R. Tarlov, and Diana Chapman Walsh, eds., Society and Health (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), esp. Donald L. Patrick and Thomas M. Wickizer, “Community and Health,” 46–92; Richard G. Wilkinson, Unhealthy Societies: From Inequality to Well-Being (New York: Routledge, 1996); Linda K. George, “Social Factors and Illness,” in Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences, 4th ed., Robert H. Binstock and Linda K. George, eds. (New York: Academic Press, 1996), 229–252; Frank W. Young and Nina Glasgow, “Voluntary Social Participation and Health,” Research on Aging 20 (1998): 339–362; Sherman A. James, Amy J. Schulz, and Juliana van Olphen, “Social Capital, Poverty, and Community Health: An Exploration of Linkages,” in Using Social Capital, Saegert, Thompson, and Warren, eds.

- B. H. Kaplan, J. C. Cassel, and S. Gore, “Social Support and Health,” Medical Care (supp.) 15, no. 5 (1977): 47–58; L. F. Berkman, “The Relationship of Social Networks and Social Support to Morbidity and Mortality,” in S. Cohen and S. L. Syme, eds., Social Support and Health (Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1985), 241–262; J. S. House, D. Umberson, and K. R. Landis, “Structures and Processes of Social Support,” Annual Review of Sociology 14 (1988): 293–318; Ichiro Kawachi, Bruce P. Kennedy, and Roberta Glass, “Social Capital and Self-Rated Health: A Contextual Analysis,” American Journal of Public Health 89 (1999): 1187–1193.

- Lisa Berkman, “The Changing and Heterogeneous Nature of Aging and Longevity: A Social and Biomedical Perspective,” Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics 8 (1988): 37–68; Lisa Berkman and Thomas Glass, “Social Integration, Social Networks, Social Support, and Health,” in Social Epidemiology, Lisa F. Berkman and Ichiro Kawachi, eds. (New York, Oxford University Press, 2000), 137–174; T. E. Seeman, L. F. Berkman, and D. Blazer, et al., “Social Ties and Support and Neuroendocrine Function: The MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging,” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 16 (1994): 95–106; Sheldon Cohen, “Health Psychology: Psychological Factors and Physical Disease from the Perspective of Human Psychoneuroimmunology,” Annual Review of Psychology 47 (1996): 113–142.

- Berkman and Glass, “Social Integration, Social Networks, Social Support, and Health.”

- Kawachi et al., “Social Capital and Self-Rated Health.”

- The Pearson’s r coefficient between the fraction reporting they were in fair or poor health and the (demographically weighted) state mistrust ranking (low, medium, high) was 0.71; the r coefficient between fraction of population in fair/poor health and the (demographically weighted) state “helpfulness” ranking (low, medium, high) was -0.66.

- The Pearson’s r coefficient between the Social Capital Index and the Morgan-Quitno health index (1991–98) across the fifty states equals 0.78, which is strong by conventional social science standards; the comparable correlation between the Social Capital Index and the age-adjusted all-cause mortality rate is -.81. Thanks to Ichiro Kawachi for providing this measure of death rates.

- Thanks to Kimberly Lochner for bringing the history of Roseto to my attention and for introducing me to the literature on the health effects of social connectedness. The key studies of Roseto are J. G. Bruhn and S. Wolf, The Roseto Story: An Anatomy of Health (Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979); S. Wolf and J. G. Bruhn, The Power of Clan: The Influence of Human Relationships on Heart Disease (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1993); B. Egolf, J. Lasker, S. Wolf, and L. Potvin, “The Roseto Effect: A Fifty-Year Comparison of Mortality Rates,” American Journal of Epidemiology 125, no. 6 (1992): 1089–1092.

- L. F. Berkman and S. L. Syme, “Social Networks, Host Resistance and Mortality: A Nine Year Follow-up of Alameda County Residents,” American Journal of Epidemiology 109 (1979): 186–204.

- J. House, C. Robbins, and H. Metzner, “The Association of Social Relationships and Activities with Mortality: Prospective Evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study,” American Journal of Epidemiology 116, no. 1 (1982): 123–140. This finding held for men only.

- House, Robbins, and Metzner (1982); this finding held for women only. T. E. Seeman, G. A. Kaplan, L. Knudsen, R. Cohen, and J. Guralnik, “Social Network Ties and Mortality among the Elderly in the Alameda County Study,” American Journal of Epidemiology 126, no. 4 (1987): 714–723; this study found that social isolation predicted mortality only in people over sixty.

- D. Blazer, “Social Support and Mortality in an Elderly Community Population,” American Journal of Epidemiology 115, no. 5 (1982): 684–694; K. Orth-Gomer and J. V. Johnson, “Social Network Interaction and Mortality,” Journal of Chronic Diseases 40, no. 10 (1987): 949–957.

- L. Welin, G. Tibblin, K. Svardsudd, B. Tibblin, S. Ander-Peciva, B. Larsson, and L. Wilhelmsen, “Prospective Study of Social Influences on Mortality,” The Lancet, April 20, 1985, 915–918; Frederick J. Manning and Terrence D. Fullerton, “Health and Well-Being in Highly Cohesive Units of the U.S. Army,” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 18 (1988): 503–519.

- Sheldon Cohen et al., “Social Ties and Susceptibility to the Common Cold,” Journal of the American Medical Association 277 (June 25, 1997): 1940–1944.

- A. Colantonio, S. V. Kasl, A. M. Ostfeld, and L. Berkman, “Psychosocial Predictors of Stroke Outcomes in an Elderly Population,” Journal of Gerontology 48, no. 5 (1993): S261–S268.

- Young and Glasgow, “Voluntary Social Participation and Health.”

- Angus Deaton and C. H. Paxson, “Aging and Inequality in Income and Health,” American Economic Review 88 (1998): 252, report “there has been no improvement, and possibly some deterioration, in health status across cohorts born after 1945, and there were larger improvements across those born before 1945.”

- R. C. Kessler et al., “Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalence of DSM-III-R Psychiatric Disorders in the United States,” Archives of General Psychiatry 51 (1994): 8–19; C. J. Murray and A. D. Lopez, “Evidence-Based Health Policy—Lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study,” Science 274 (1996): 740–743; L. I. Pearlin et al., “The Stress Process”; G. A. Kaplan et al., “Psychosocial Predictors of Depression”; A. G. Billings and R. H. Moos, “Life Stressors and Social Resources Affect Posttreatment Outcomes among Depressed Patients,” Journal of Abnormal Psychiatry 94 (1985): 140–153; C. D. Sherbourne, R. D. Hays, and K. B. Wells, “Personal and Psychosocial Risk Factors for Physical and Mental Health Outcomes and Course of Depression among Depressed Patients,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 63 (1995): 345–355; T. E. Seeman and L. F. Berkman, “Structural Characteristics of Social Networks and Their Relationship with Social Support in the Elderly: Who Provides Support,” Social Science and Medicine 26 (1988): 737–749. I am indebted to Julie Donahue for her fine work on this topic.

- L. I. Pearlin, M. A. Lieberman, E. G. Menaghan, and J. T. Mullan, “The Stress Process,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 22, no. 4 (1981): 337–356; A. Billings and R. Moos, “Social Support and Functioning among Community and Clinical Groups: A Panel Model,” Journal of Behavioral Medicine 5, no. 3 (1982): 295–311; G. A. Kaplan, R. E. Roberts, T. C. Camacho, and J. C. Coyne, “Psychosocial Predictors of Depression,” American Journal of Epidemiology 125, no. 2 (1987), 206–220; P. Cohen, E. L. Struening, G. L. Muhlin, L. E. Genevie, S. R. Kaplan, and H. B. Peck, “Community Stressors, Mediating Conditions and Well-being in Urban Neighborhoods,” Journal of Community Psychology 10 (1982): 377–391; David G. Myers, “Close Relationships and Quality of Life,” in D. Kahneman, E. Diener, and N. Schwartz, eds., Well-being: The Foundation of Hedonic Psychology (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1999).

- Michael Argyle, The Psychology of Happiness (London: Methuen, 1987); Ed Diener, “Subjective Well-being,” Psychological Bulletin 95 (1984): 542–575; Ed Deiner, “Assessing Subjective Well-being,” Social Indicators Research, 31 (1994): 103–175; David G. Myers and Ed Deiner, “Who Is Happy?” Psychological Science 6 (1995): 10–19; Ruut Veenhoven, “Developments in Satisfaction-Research,” Social Indicators Research, 37 (1996): 1–46; and works cited there.

- In these data and in most studies the effect of marriage on life happiness is essentially identical among men and women, contrary to some reports that marriage has a more positive effect on happiness among men.

- Income in successive Life Style surveys is measured in terms of income brackets, defined in dollars of annual income. To enhance comparability over time, we have translated each of these brackets in each annual survey into its mean percentile ranking in that year’s income distribution. The effect of income measured in percentiles on contentment is not linear, but that is offset by the fact that the translation of income in dollars to income percentiles is also not linear. Thus the “happiness equivalent” of any particular change in income is accurate in its order of magnitude, but not in detail.

- The results here are based on multiple regression analyses on the DDB Needham Life Style sample, including age, gender, education, income, marital status, as well as our various measures of civic engagement. The results are essentially identical for men and women, except that the effects of education and of social connections on happiness are slightly greater among women. Income, education, and social connections all have a greater effect among single people than among married people. For example, the effects of club meetings on the happiness of single people is twice as great as on the happiness of married people. In other words, absent marriage, itself a powerful booster of life contentment, other factors become more important. Conversely, even among the poor, uneducated, and socially isolated, marriage provides a fundamental buffer for contentment.

- Author’s analysis of DDB Needham Life Style and Harris poll data.

- Martin E. P. Seligman, “Boomer Blues,” Psychology Today, October 1988, 50–55.