The environment affects gene action

The phenotype of an individual does not result from its genotype alone. Genotype and environment interact to determine the phenotype of an organism. This is especially important to remember in the era of genome sequencing (covered in Chapter 17). When the sequence of the human genome was completed in 2003, it was hailed as the “book of life,” and public expectations of the benefits gained from this knowledge were (and are) high. But this kind of “genetic determinism” is wrong. You already know that environmental variables such as light, temperature, and nutrition can affect the phenotypic expression of a genotype.

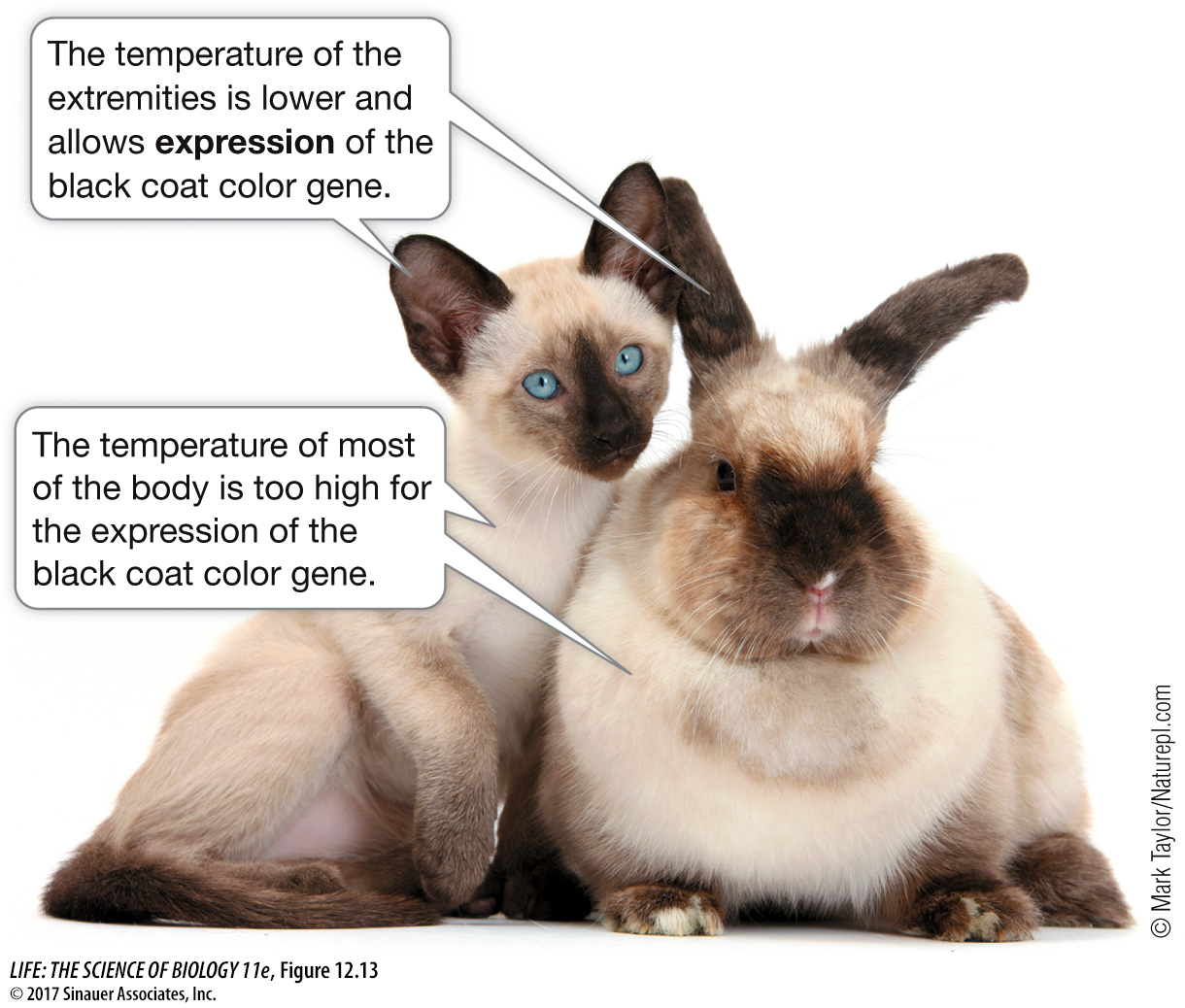

A familiar example of this phenomenon involves “point restriction” coat patterns found in Siamese cats and certain rabbit breeds (Figure 12.13). These animals carry a mutant allele of a gene that controls the growth of dark fur all over the body. As a result of this mutation, the enzyme encoded by the gene is inactive at temperatures above a certain point (usually around 35°C). The animals maintain a body temperature above this point, and so their fur is mostly light. However, the extremities—

A simple experiment shows that the dark fur is temperature-

Two parameters describe the effects of genes and environment on the phenotype:

Penetrance is the proportion of individuals in a group with a given genotype that actually show the expected phenotype. For example, many people who inherit a mutant allele of the gene BRCA1 develop breast cancer. But, some people with the mutation do not. So the BRCA1 allele is said to be incompletely penetrant.

Expressivity is the degree to which a genotype is expressed in an individual. For example, a woman with the mutant BRCA1 allele may develop both breast and ovarian cancer as part of the phenotype, but another woman with the same mutation may develop only breast cancer. So the mutant allele is said to have variable expressivity.