Mendel’s laws can be observed in human pedigrees

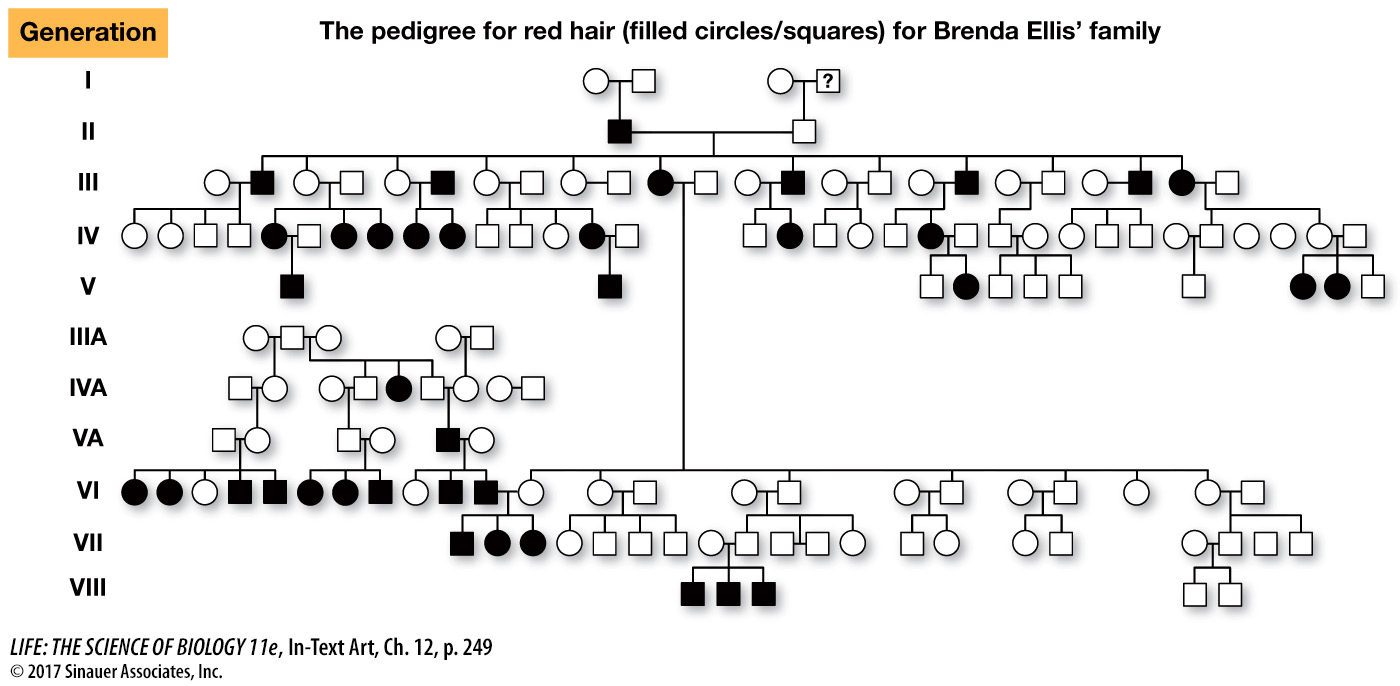

Mendel worked out his laws by doing many planned crosses with pea plants and counting many offspring. Neither of these approaches is possible with humans, so human geneticists rely on pedigrees: family trees that show the occurrence of phenotypes (and alleles) in several generations of related individuals. You saw an example of this in the opening story of this chapter. On the next page is the eight-

Because humans have small numbers of offspring, human pedigrees do not show the clear proportions of phenotypes that Mendel saw in his pea plants. For example, when a man and a woman who are both heterozygous for a recessive allele (say, Aa) have children together, each child has a ¼ probability of being a recessive homozygote (aa). If this couple were to have several dozen children, about one-

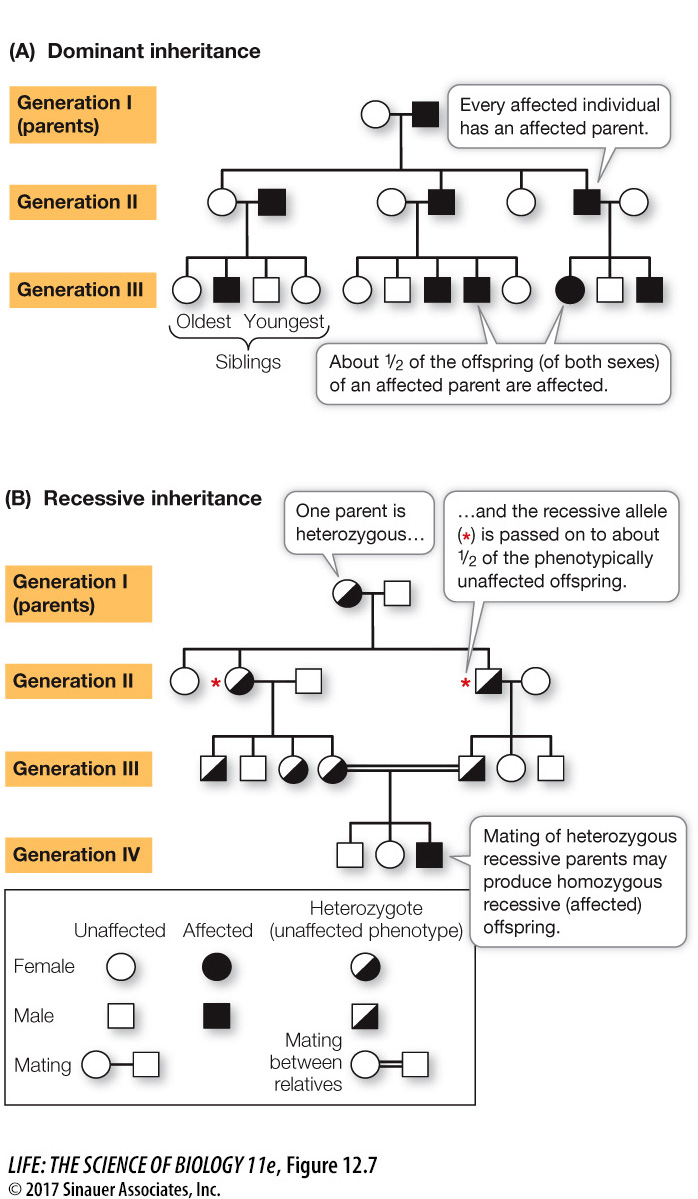

Figure 12.7A is a pedigree showing the pattern of inheritance of a rare dominant allele. The following are the key features to look for in such a pedigree:

Activity 12.2 Pedigree Analysis

www.life11e.com/

Every affected person has an affected parent.

About half of the offspring of an affected parent are also affected. (This is easiest to observe among the 12 cousins in generation III.)

249

Compare this pattern with the one shown in Figure 12.7B, which is typical for the inheritance of a rare recessive allele:

Affected people can have two parents who are not affected.

Only a small proportion of people are affected: about one-

fourth of children whose parents are both heterozygotes.

In the families of individuals who have a rare recessive phenotype, it is not uncommon to find a marriage of two relatives. This observation is a result of the rarity of recessive alleles that give rise to abnormal phenotypes. For two phenotypically normal parents to have an affected child (aa genotype), the parents must both be heterozygous (Aa). If a particular recessive allele is rare in the general population, the chance of two people mating to produce offspring who are both carrying that allele is quite low. However, if that allele is present in a family, two cousins might share it (see Figure 12.7B). For this reason, studies on populations that are isolated either culturally (by religion, as with the Amish in the United States) or geographically (as on islands) have been extremely valuable to human geneticists. People in these groups are more likely to marry relatives who may carry the same rare recessive alleles.

250