Viruses undertake two kinds of reproductive cycles

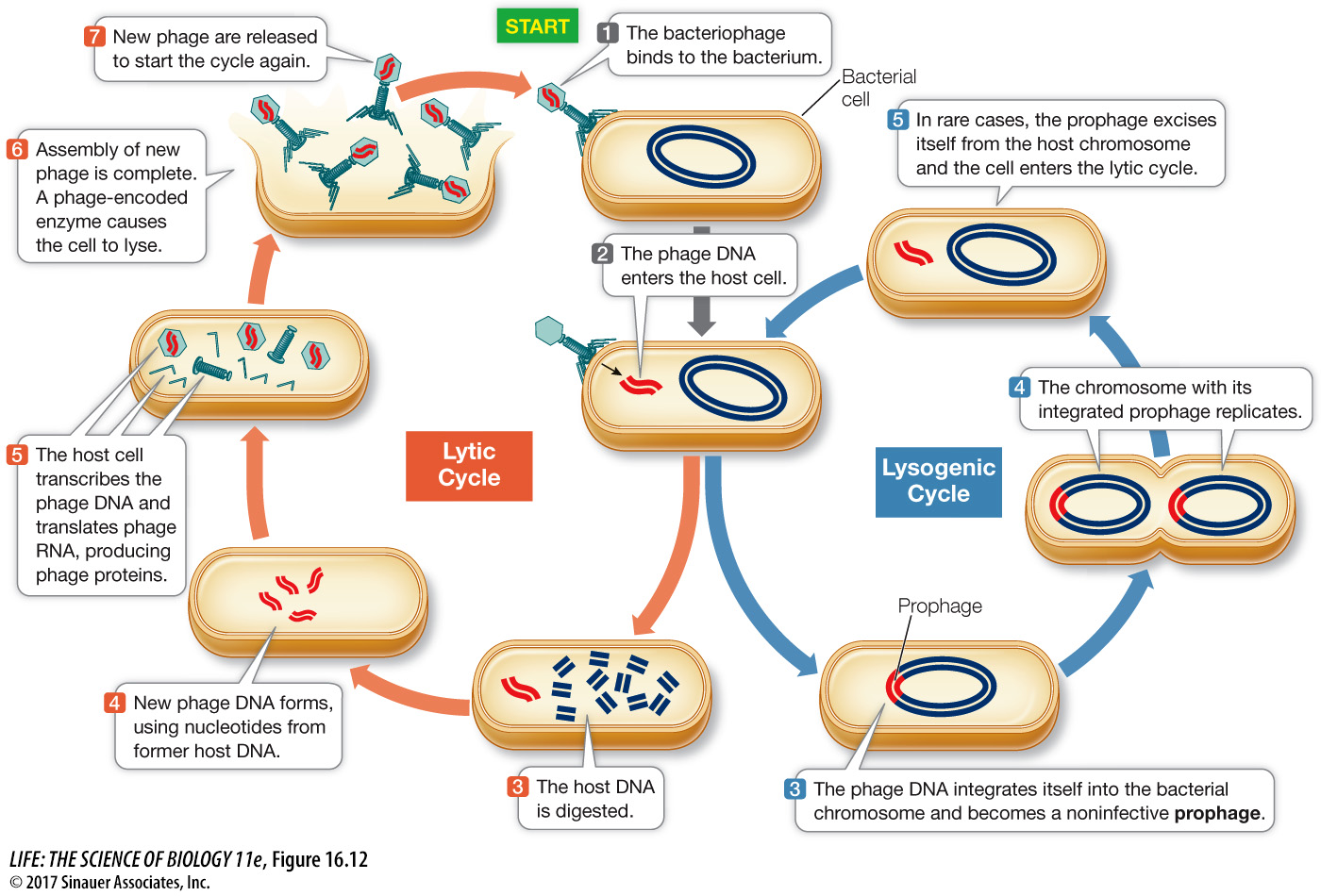

After a viral genome enters a cell, typically the invader takes over the cells’ molecular genetic machinery. But in some cases, there is an alternate series of events, in which the viral genome becomes integrated into the host genome.

LYTIC CYCLE The Hershey–

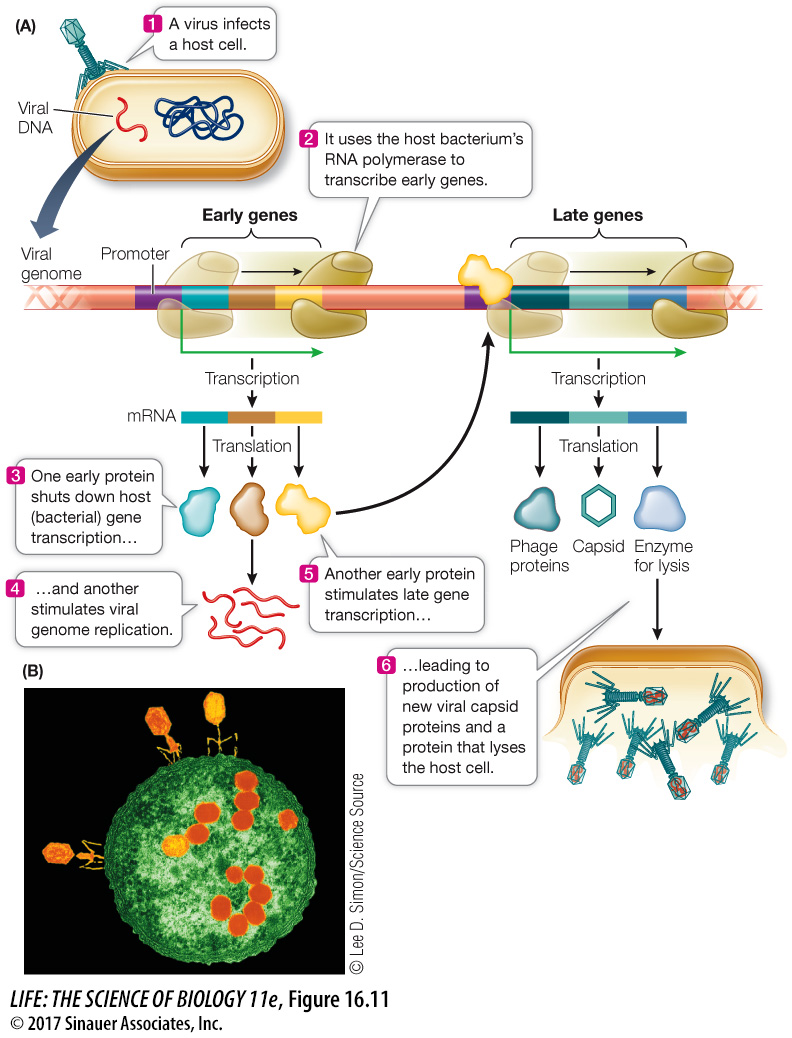

At the molecular level, the reproductive cycle of a typical lytic virus has two stages: early and late, as illustrated in Figure 16.11. Follow along in the text and Figure 16.11 and you’ll see examples of both positive and negative regulation, which stimulate and inhibit, respectively, gene expression:

The viral genome contains a promoter that binds host RNA polymerase. In the early stage (1–

2 min after phage DNA entry), viral genes that lie adjacent to this promoter are transcribed (positive regulation). These early genes often encode proteins that shut down host transcription (negative regulation) and stimulate viral genome replication and transcription of viral late genes (positive regulation). Three minutes after DNA entry, viral nuclease enzymes digest the host’s chromosome, providing nucleotides for the synthesis of viral genomes.

In the late stage, viral late genes are transcribed (positive regulation); they encode the proteins that make up the capsid (the outer shell of the virus) and other protein components of the virus and enzymes that lyse the host cell to release the new virions. This begins 9 min after DNA entry and 6 min before the first new phage particles appear.

The entire process—

LYSOGENIC CYCLE Like all nucleic acid genomes, those of viruses can mutate and evolve by natural selection. Some viruses have evolved an advantageous process called lysogeny that postpones the lytic cycle. In lysogeny, the viral DNA becomes integrated into the host DNA and becomes a prophage (Figure 16.12). As the host cell divides, the viral DNA gets replicated along with that of the host. The prophage can remain inactive within the bacterial genome for thousands of generations, producing many copies of the original viral DNA.

347

However, if the host cell is not growing well, the virus “cuts its losses.” It switches to a lytic cycle, in which the prophage excises itself from the host chromosome and reproduces. In other words, the virus is able to enhance its chances of multiplication and survival by inserting its DNA into the host chromosome, where it sits as a silent passenger until conditions are right for lysis.