Directional selection favors one extreme

Directional selection is operating when individuals at one extreme of a character distribution contribute more offspring to the next generation than other individuals do, shifting the average value of that character in the population toward that extreme. The opening story in this chapter describes directional selection for improved echolocation abilities in bats over time, and also directional selection for improved ultrasound hearing in their prey.

In the case of a single gene locus, directional selection may result in favoring a particular genetic variant—

If directional selection operates over many generations, an evolutionary trend is seen in the population (see Figure 20.12B). Evolutionary trends often continue for many generations, but they can be reversed if the environment changes and different phenotypes are favored, or halted when an optimal phenotype is reached or trade-

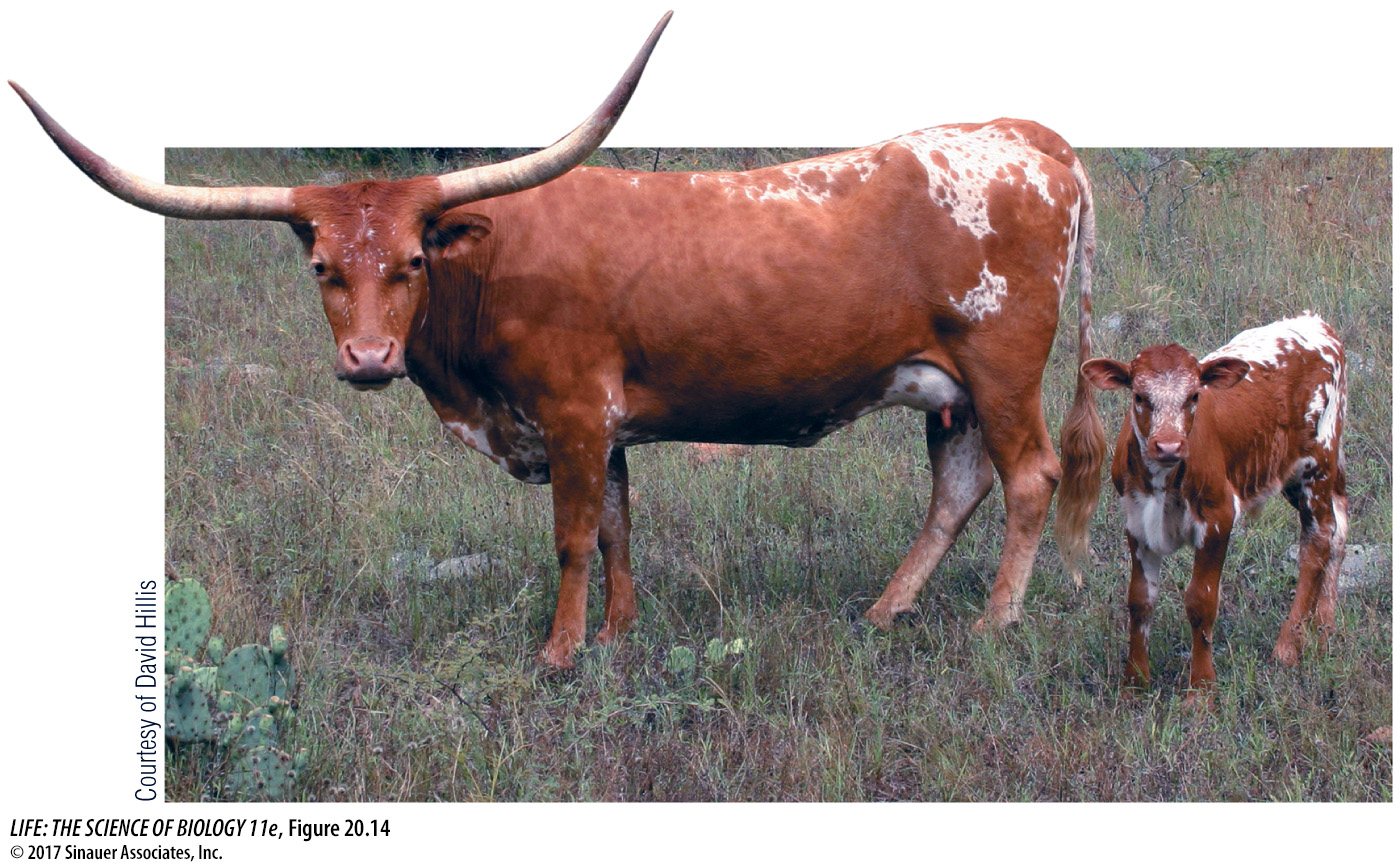

The long horns of Texas Longhorn cattle (Figure 20.14) are an example of a trait that has evolved through directional selection. Texas Longhorns are descendants of cattle brought to the New World by Christopher Columbus, who picked up a few cattle in the Canary Islands and brought them to the island of Hispaniola in 1493. The cattle multiplied, and their descendants were taken to the mainland of Mexico. Spaniards exploring what would become Texas and the southwestern United States brought these cattle with them, some of which escaped and formed feral herds. Populations of feral cattle increased greatly over the next few hundred years, but there was heavy predation from bears, mountain lions, and wolves, especially on the young calves. Cows with longer horns were more successful in protecting their calves against attacks, and over a few hundred years the average horn length in the feral herds increased considerably. In addition, the cattle evolved resistance to endemic diseases of the Southwest, as well as higher fecundity and longevity. Texas Longhorns often live and produce calves well into their twenties—