Darwin and Wallace introduced the idea of evolution by natural selection

In the early 1800s, it was not yet evident to many people that populations of living organisms evolve. But several biologists had suggested that the species living on Earth had changed over time—

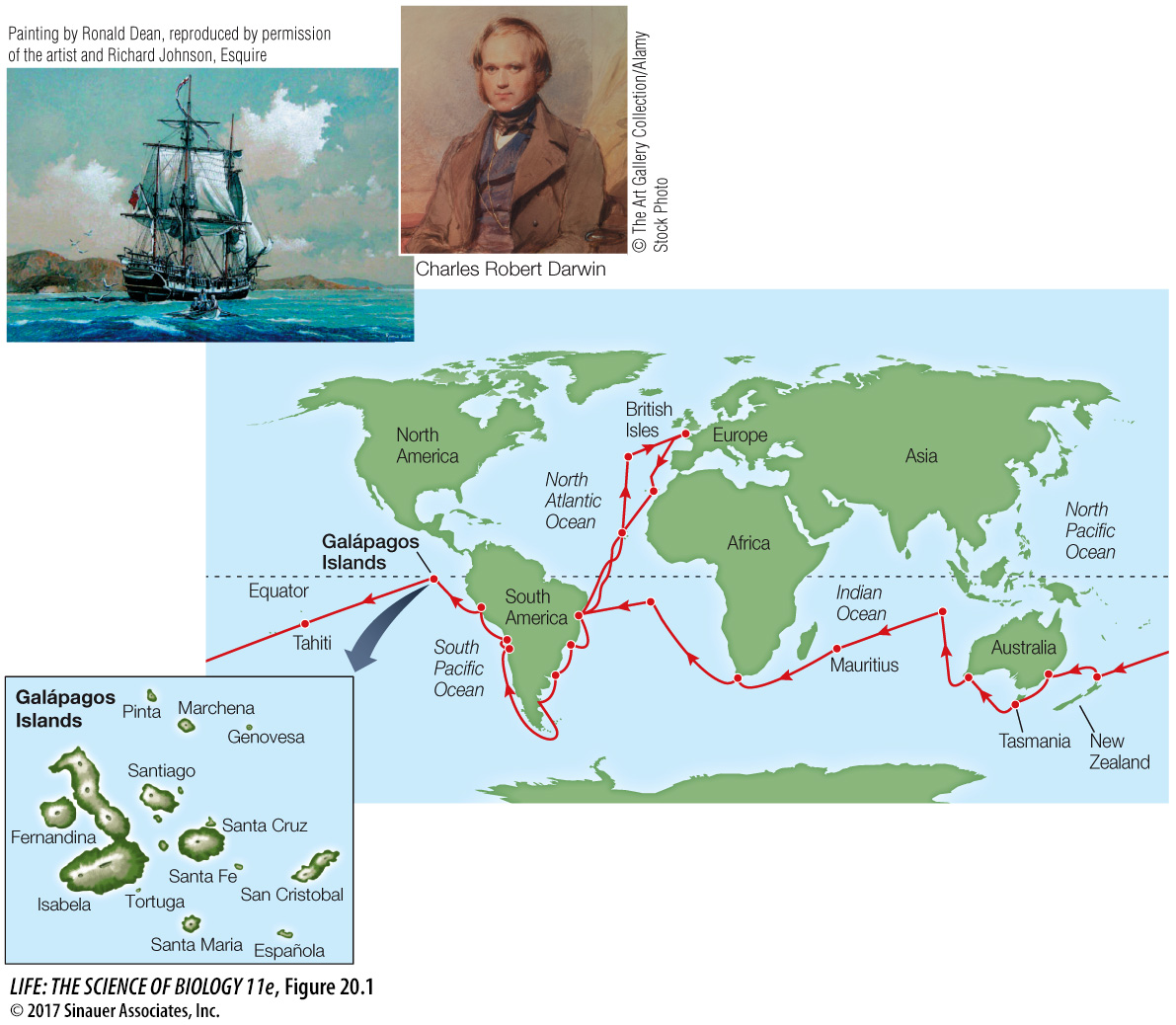

In the 1820s, a young Charles Darwin became passionately interested in the subjects of geology (with its new sense of Earth’s great age) and natural history (the scientific study of how different organisms function and carry out their lives in nature). Despite these interests, he planned, at his father’s behest, to become a doctor. But surgery conducted without anesthesia nauseated Darwin, and he gave up medicine to study at Cambridge University for a career as a clergyman in the Church of England. Always more interested in science than in theology, he gravitated toward scientists on the faculty, especially the botanist John Henslow. In 1831, Henslow recommended Darwin for a position on HMS Beagle, a Royal Navy vessel that was preparing for a survey voyage around the world (Figure 20.1).

Activity 20.1 Darwin’s Voyage

www.life11e.com/

Whenever possible during the five-

When he returned to England in 1836, Darwin continued to ponder his observations. His thoughts were strongly influenced by the geologist Charles Lyell, who had recently popularized the idea that Earth had been shaped by slow-

Species are not immutable; they change over time.

Divergent species share a common ancestor and have diverged from one another gradually over time (a concept Darwin termed descent with modification).

Changes in species over time can be explained by natural selection: the increased survival and reproduction of some individuals compared with others, based on differences in their traits.

426

The first of these propositions was not unique to Darwin; several earlier authors had argued for the fact of evolution. A more revolutionary idea was his second proposition, that divergent species are related to one another through common descent. But Darwin is probably best known for his third proposition, that of natural selection.

Darwin realized that many more individuals of most species are born than survive to reproduce. He also knew that, although offspring usually resemble their parents, offspring are not identical to one another or to either parent. Finally, he was well aware that human breeders of plants and animals often selected their breeding stock based on the occurrence of particular traits. Over time, this selection resulted in dramatic changes in the appearance of the descendants of those plants or animals. In natural populations, wouldn’t the individuals with the best chances of survival and reproduction be similarly “selected,” and thus pass their traits on to the next generation? Darwin’s simple but powerful idea was that nature did the selecting in natural populations on the basis of traits that resulted in greater survival and, eventually, greater likelihood of reproduction.

In 1844, Darwin wrote a long essay describing the role of natural selection as a process of evolution. But he was reluctant to publish it, preferring to assemble more evidence first. Darwin’s hand was forced in 1858, when he received a letter and manuscript from another traveling English naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace, who was studying the plants and animals of the Malay Archipelago. Wallace asked Darwin to evaluate his manuscript, which included an explanation of natural selection almost identical to Darwin’s. Darwin was at first dismayed, believing Wallace to have preempted his idea. Parts of Darwin’s 1844 essay, together with Wallace’s manuscript, were presented to the Linnaean Society of London on July 1, 1858, thereby crediting both men for the idea of natural selection. Darwin then worked quickly to finish his full-

Animation 20.1 Natural Selection

www.life11e.com/

Although Darwin and Wallace independently articulated the concept of natural selection, Darwin developed his ideas first. Furthermore, On the Origin of Species proved to be a stunning work of scholarship that provided exhaustive evidence from many fields supporting both the premise of evolution itself and the understanding of natural selection as a process of evolution. Thus both concepts are more closely associated with Darwin than with Wallace.

427

The publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859 stirred considerable interest (and controversy) among scientists and the public alike. Scientists spent much of the rest of the nineteenth century amassing biological and paleontological data to test evolutionary ideas and document the history of life on Earth. By 1900, the fact of biological evolution (defined at that time as change in the physical characteristics of populations over time) was established beyond any reasonable doubt. As biologists discovered the details of genetic inheritance in the twentieth century, the genetic mechanisms of evolution became clear. The development of methods for sequencing DNA in the late 1970s allowed biologists to document evolutionary changes within and between species with great precision. This technology led to explosive growth in the field of evolutionary biology. In the past three decades, well over a quarter of a million scientific papers on evolutionary observations, experiments, and theory have been published.