Physical barriers give rise to allopatric speciation

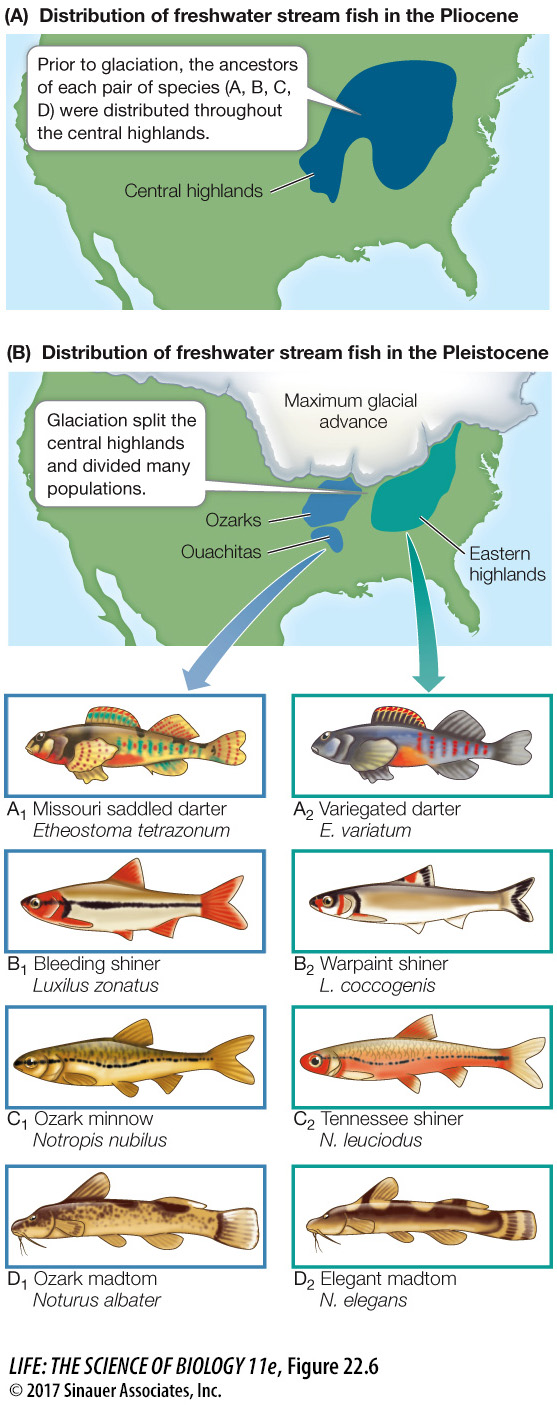

Speciation that results when a population is divided by a physical barrier is known as allopatric speciation (Greek allos, “other,” + patria, “homeland”). Allopatric speciation is thought to be the dominant mode of speciation in most groups of organisms. The physical barrier that divides the range of a species may be a body of water or a mountain range for terrestrial organisms, or dry land for aquatic organisms—

473

focus: key figure

Question

Q: After the retreat of the glaciers, why did the fish species in the Ozarks and Ouachitas remain reproductively isolated from those in the Appalachians to the east?

The glaciers eliminated most of the highlands that formerly connected the two areas, so there is now little appropriate habitat that would allow the differentiated species to interact. But if the interactions were possible, it is likely that the hybrids would exhibit reduced fitness (as explained by the Dobzhansky–Muller model), and there would be selection for prezygotic isolating mechanisms that would minimize hybridization.

Animation 22.1 Speciation Mechanisms

www.life11e.com/

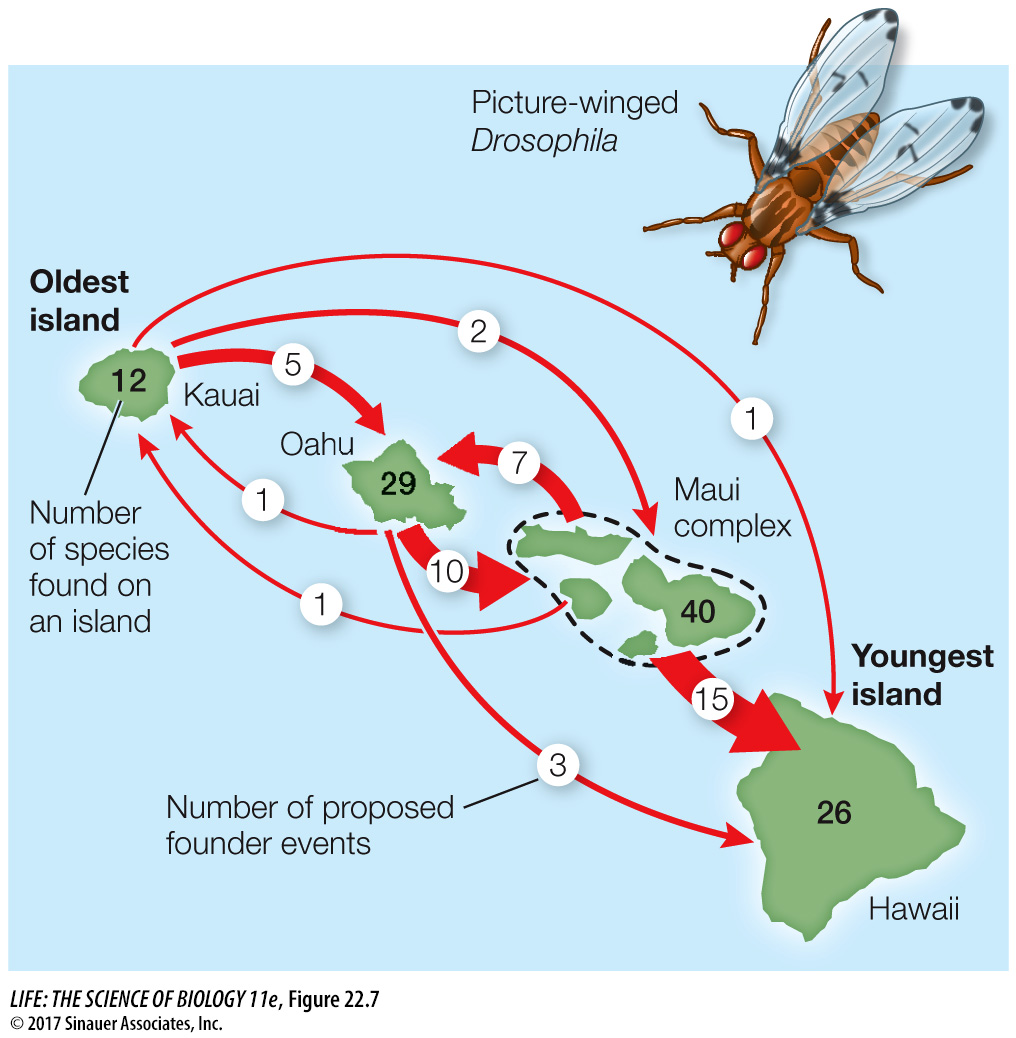

Allopatric speciation may also result when some members of a population cross an existing barrier and establish a new, isolated population. Many of the more than 800 species of Drosophila found in the Hawaiian Islands are restricted to a single island. We know that these species are the descendants of new populations founded by individuals dispersing among the islands when we find that the closest relative of a species on one island is a species on a neighboring island rather than a species on the same island. Biologists who have studied the chromosomes of these fruit flies estimate that speciation in this group of Drosophila has resulted from at least 45 such founder events (Figure 22.7).

Animation 22.2 Founder Events and Allopatric Speciation

www.life11e.com/

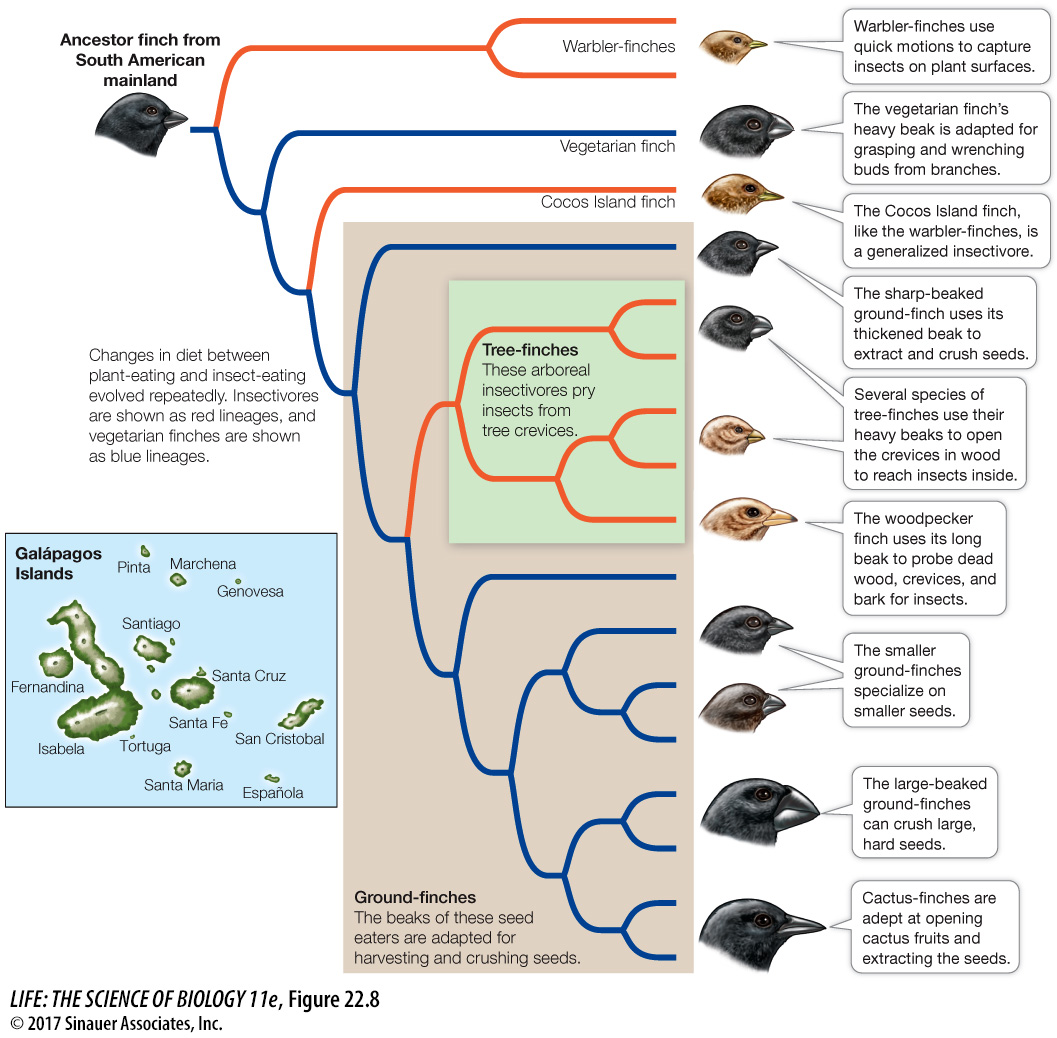

The species of finches found in the islands of the Galápagos archipelago, some 1,000 km off the coast of Ecuador, are one of the most famous examples of allopatric speciation. Darwin’s finches (as they are usually called, because Darwin was the first scientist to study them) arose in the Galápagos from a single South American finch species that colonized the islands. Today the Galápagos species differ strikingly not only from their closest mainland relative, but also from one another (Figure 22.8). The islands are sufficiently far apart that the birds move among them only infrequently. In addition, environmental conditions differ widely from island to island. Some islands are relatively flat and arid; others have forested mountain slopes. Sister lineages on different islands have diverged over hundreds of thousands of years, and several feeding specializations have arisen on different islands with different environments. Although finches occasionally fly between islands, an immigrant finch population is not likely to become established unless the new environment is appropriate for its feeding specialization, and no other similar species are already present on the island. Each island now has from 1 to 4 species of finches, and biologists recognize between 14 and 18 species across the archipelago.