Several ecological and behavioral factors influence speciation rates

Many factors can influence rates of speciation across groups, including the diet, behavioral complexity, and dispersal abilities of the respective species.

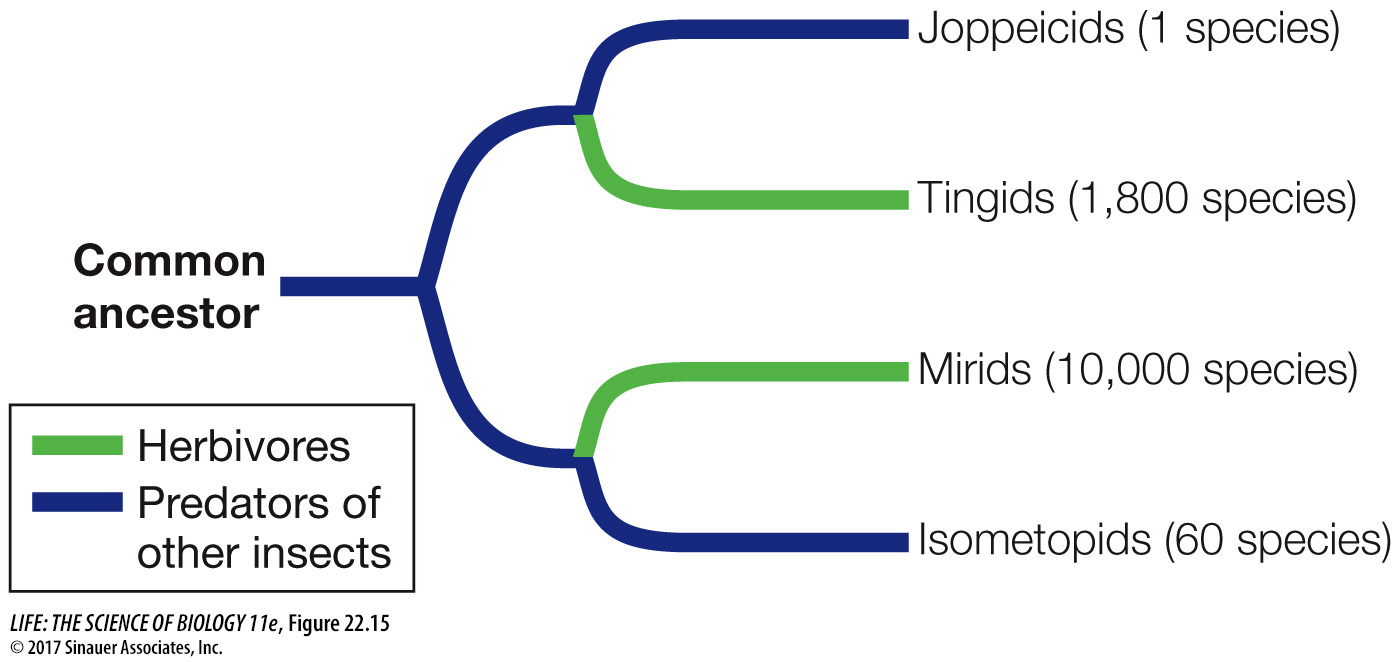

DIET SPECIALIZATION Populations of species that have specialized diets may be more likely to diverge than those with more generalized diets. To investigate the effects of diet specialization on rates of speciation, Charles Mitter and colleagues compared species richness in some closely related groups of true bugs (hemipterans). The common ancestor of these groups was a predator that fed on other insects, but a dietary shift to herbivory (eating plants) evolved at least twice in the groups under study. Herbivorous bugs typically specialize on one or a few closely related species of plants, whereas predatory bugs tend to feed on many different species of insects. A high diversity of host-

POLLINATION Speciation rates are faster in animal-

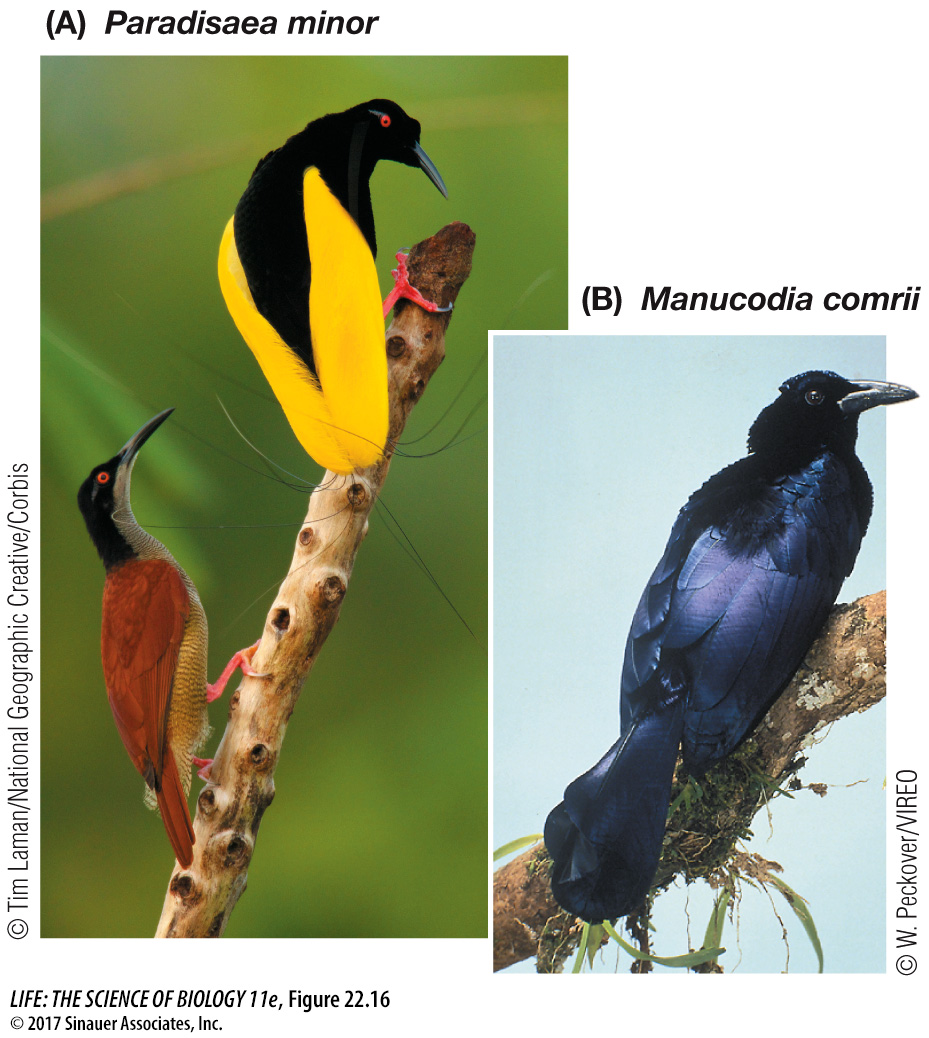

SEXUAL SELECTION It appears that the mechanisms of sexual selection (see Key Concept 20.2) result in high rates of speciation, as we saw in the case of the cichlids of Lake Malawi. Some of the most striking examples of sexual selection are found in birds with polygynous mating systems. Birdwatchers travel thousands of miles to Papua New Guinea to witness the mating displays of male birds of paradise, which have brightly colored plumage (Figure 22.16A) and look distinctly different from females of their species—

482

The closest relatives of the birds of paradise are the manucodes (Figure 22.16B). Male and female manucodes differ only slightly in size and plumage (they are sexually monomorphic). They form monogamous pair bonds, and both sexes contribute to raising the young. There are only 5 species of manucodes, compared with 33 species of birds of paradise. By itself, this one comparison would not be convincing evidence that sexually dimorphic clades have higher rates of speciation than do monomorphic clades. However, when biologists examined all the examples of birds in which one clade is sexually dimorphic and the most closely related clade is sexually monomorphic, the sexually dimorphic clades were significantly more likely to contain more species. But why would sexual dimorphism be associated with a higher rate of speciation?

Animals with complex sexually selected behaviors are likely to form new species at a high rate because they make sophisticated discriminations among potential mating partners. They distinguish members of their own species from members of other species, and they make subtle discriminations among members of their own species on the basis of size, shape, appearance, and behavior. Such discriminations can greatly influence which individuals are most successful in mating and producing offspring, so they may lead to rapid evolution of behavioral isolating mechanisms among populations.

DISPERSAL ABILITY Speciation rates are usually higher in groups with poor dispersal abilities than in groups with good dispersal abilities because even narrow barriers can be effective in dividing a species whose members are highly sedentary. Until recently, the Hawaiian Islands had about 1,000 species of land snails, many of which were restricted to a single valley. Because snails move only short distances, the high ridges that separate the valleys were effective barriers to their dispersal. Unfortunately, introductions of other species and changes in habitat have resulted in the recent extinction of most of these unique Hawaiian land snails.