Rapid speciation can lead to adaptive radiation

The rapid proliferation of a large number of descendant species from a single ancestor species is called an evolutionary radiation. Evolutionary radiations often occur when a species colonizes a new area, such as an island archipelago that contains no other closely related species, because of the large number of open ecological niches. If such a rapid proliferation of species results in an array of species that live in a variety of environments and differ in the characteristics they use to exploit those environments, it is referred to as an adaptive radiation.

Several remarkable adaptive radiations have occurred in the Hawaiian Islands. In addition to its 1,000 species of land snails, the native Hawaiian biota includes 1,000 species of flowering plants, 10,000 species of insects, and more than 100 bird species. However, there were no amphibians, no terrestrial reptiles, and only one native terrestrial mammal (a bat) on the islands until humans introduced additional species. The 10,000 known native species of insects on Hawaii are believed to have evolved from about 400 immigrant species; only 7 immigrant species are believed to account for all the native Hawaiian land birds. Similarly, as we saw earlier in this chapter, an adaptive radiation in the Galápagos archipelago resulted in the many species of Darwin’s finches, which differ strikingly in the size and shape of their bills and, accordingly, in the food resources they use (see Figure 22.8).

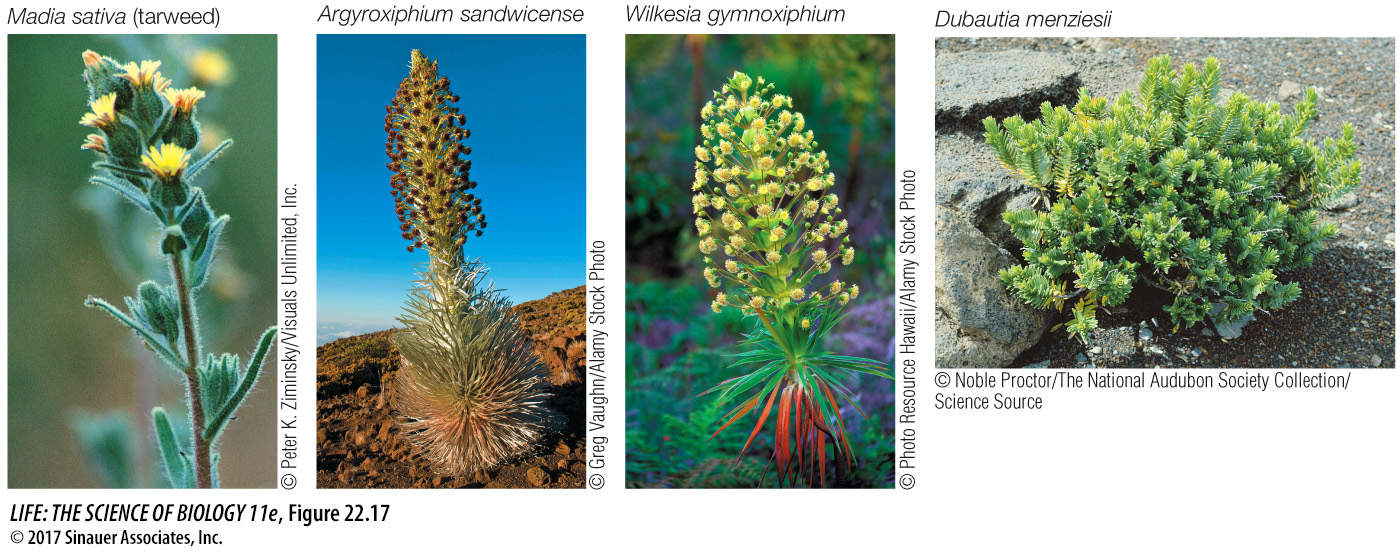

The 28 species of Hawaiian sunflowers called silverswords are an impressive example of an adaptive radiation in plants (Figure 22.17). DNA sequences show that these species share a relatively recent common ancestor with a species of tarweed from the Pacific coast of North America. Whereas all mainland tarweeds are small, upright herbs (nonwoody plants such as Madia sativa; see Figure 22.17), the silverswords include shrubs, trees, and vines as well as both upright and ground-

The Hawaiian silverswords are more diverse in size and shape than the mainland tarweeds because their tarweed ancestors first arrived on islands that harbored very few plant species. In particular, there were few trees and shrubs because such large-