key concept 23.2 Genomes Reveal Both Neutral and Selective Processes of Evolution

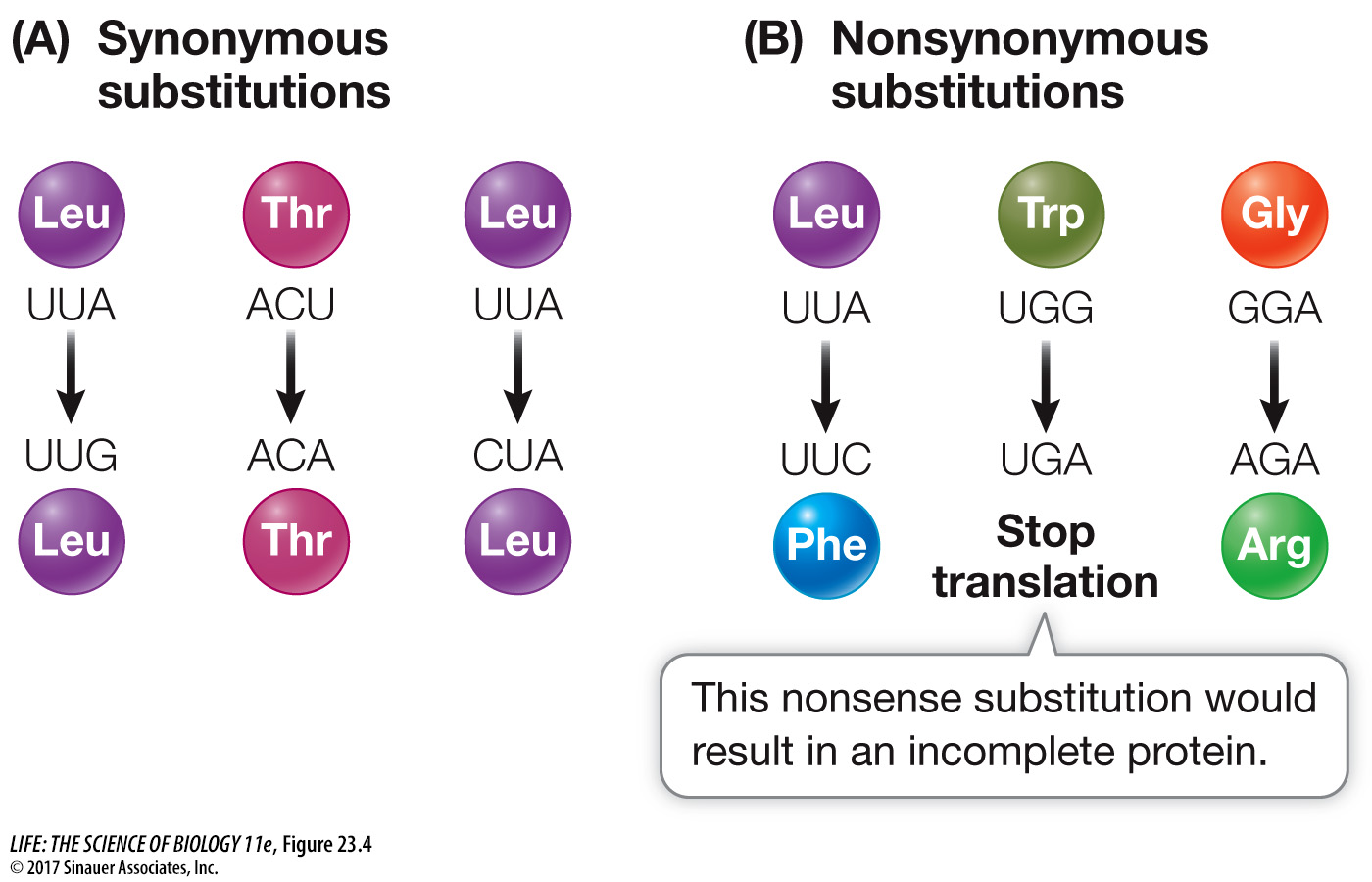

A mutation, as we saw in Key Concept 12.2, is any change in the genetic material. A nucleotide substitution is the product of one type of mutation, incorporated into a population. Many nucleotide substitutions have no effect on phenotype, even if the change occurs in a gene that encodes a protein, because most *amino acids are specified by more than one codon (see Figure 14.4). A substitution that does not change the encoded amino acid is known as a synonymous substitution or silent substitution (Figure 23.4A). Synonymous substitutions do not affect the functioning of a protein (although they may have other effects, as described in Key Concept 15.1) and are therefore less likely than other types of substitutions to be subject to natural selection.

491

focus your learning

Neutral evolution is distinguished from purifying and positive selection by its lack of effect on the survival and reproduction of the organism.

The rate of fixation of neutral nucleotide changes within populations is independent of population size.

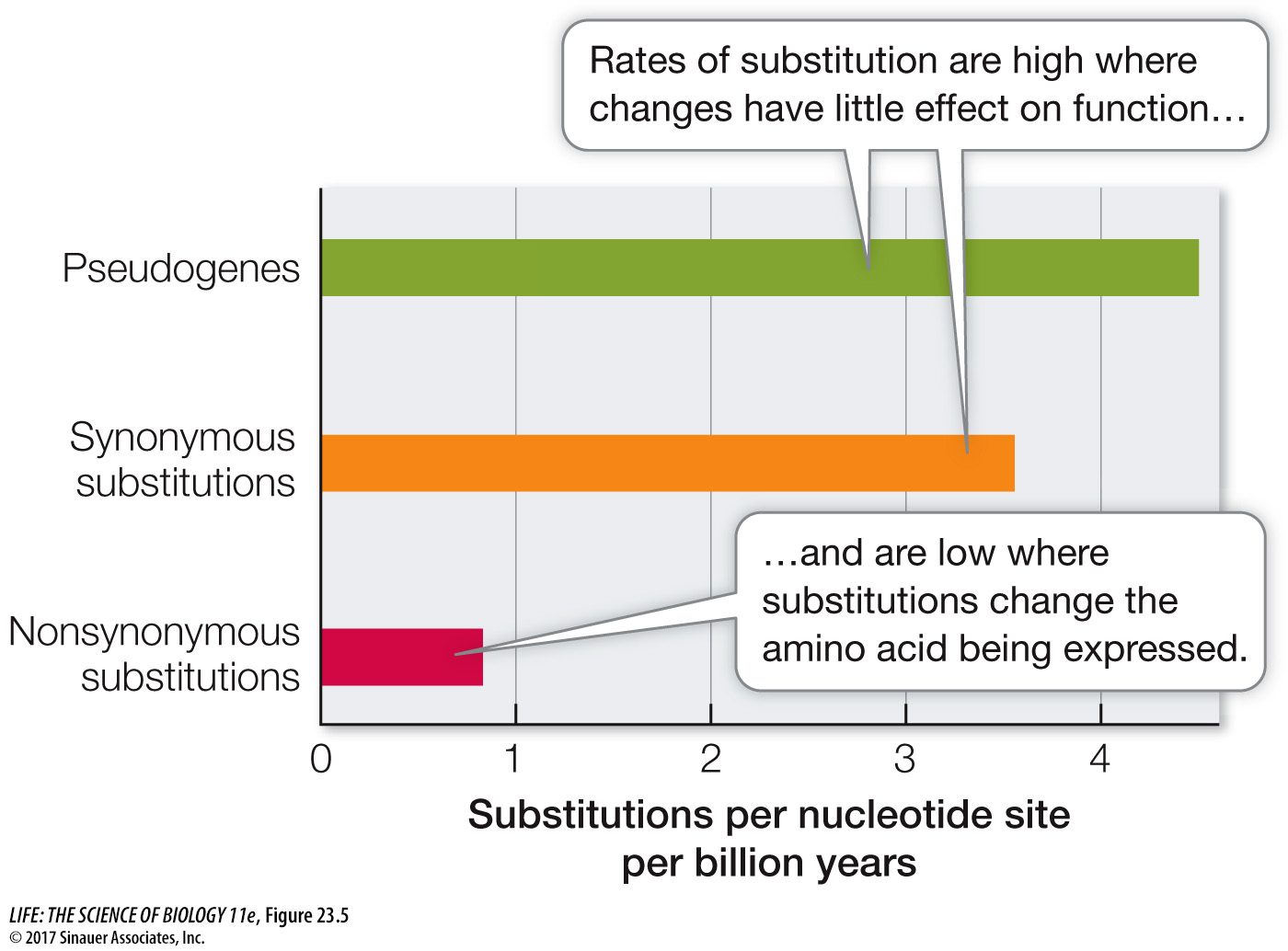

Comparing rates of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions can be used to identify positive and purifying selection in protein genes.

Genome sizes vary widely among organisms, even though the number of protein-

coding genes shows much less variation.

*connect the concepts The genetic code determines the amino acid that is encoded by each codon; see Figure 14.5.

A nucleotide substitution that does change the amino acid sequence encoded by a gene is known as a nonsynonymous substitution (Figure 23.4B). Nonsynonomous substitutions include missense substitutions that change the specified amino acid, and nonsense substitutions that produce a stop codon and terminate the protein. In general, nonsynonymous substitutions are likely to be deleterious to the organism. But not every amino acid replacement alters a protein’s shape and charge (and hence its functional properties), so some nonsynonymous substitutions may also be selectively neutral (or nearly so). Conversely, an amino acid replacement that confers an advantage to the organism would result in positive selection for the corresponding nonsynonymous substitution.

492

Investigators have measured the average rate of nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions in some highly conserved protein-

Most natural populations harbor far more genetic variation than we would expect to find if genetic variation were influenced by natural selection alone. This discovery, combined with the knowledge that many mutations do not change molecular function, stimulated the development of the neutral theory of molecular evolution.