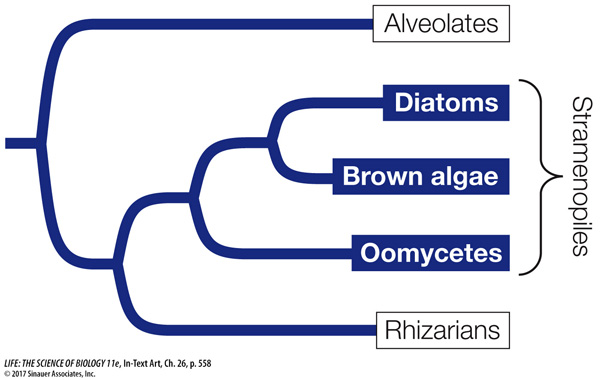

Stramenopiles typically have two unequal flagella, one with hairs

A morphological synapomorphy of most stramenopiles is the possession of rows of tubular hairs on the longer of their two flagella. Some stramenopiles lack flagella, but they are descended from ancestors that possessed flagella. The stramenopiles include the diatoms and the brown algae, which are photosynthetic, and the oomycetes, which are not.

559

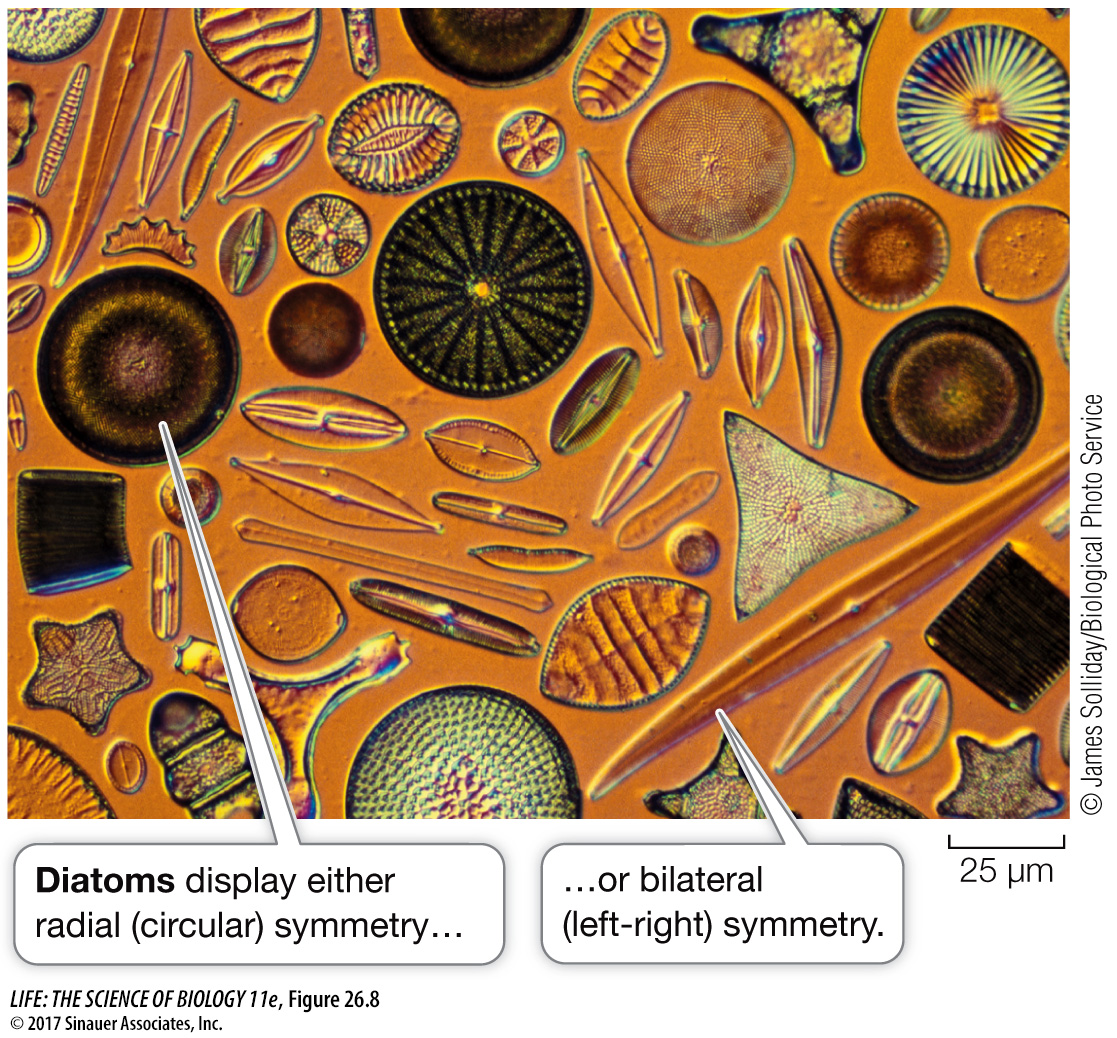

DIATOMS All of the diatoms are unicellular, although some species associate in filaments. Many have sufficient carotenoids in their chloroplasts to give them a yellow or brownish color. All of them synthesize carbohydrates and oils as photosynthetic storage products. Diatoms lack flagella except in male gametes.

Architectural magnificence on a microscopic scale is the hallmark of the diatoms. Almost all diatoms deposit silica (hydrated silicon dioxide) in their cell walls. The cell wall of a diatom is constructed in two pieces, with the top overlapping the bottom like the top of a petri dish. The silica-

Media Clip 26.2 Diatoms in Action

www.life11e.com/

Diatoms reproduce both sexually and asexually. Asexual reproduction by binary fission is somewhat constrained by the stiff cell wall. Both the top and bottom of the “petri dish” become tops of new “dishes” without changing appreciably in size. As a result, the new cell made from the former bottom is smaller than the parent cell. If this process continued indefinitely, one cell line would simply vanish, but sexual reproduction largely solves this potential problem. Gametes are formed, shed their cell walls, and fuse. The resulting zygote then grows substantially in size before a new cell wall is laid down.

Diatoms are found in all the oceans and are frequently present in great numbers. They are major photosynthetic producers in coastal waters (see Key Concept 26.4) and are among the dominant organisms in the dense “blooms” of phytoplankton that occasionally appear in the open ocean. Diatoms are also common in fresh water and even occur on the wet surfaces of terrestrial mosses.

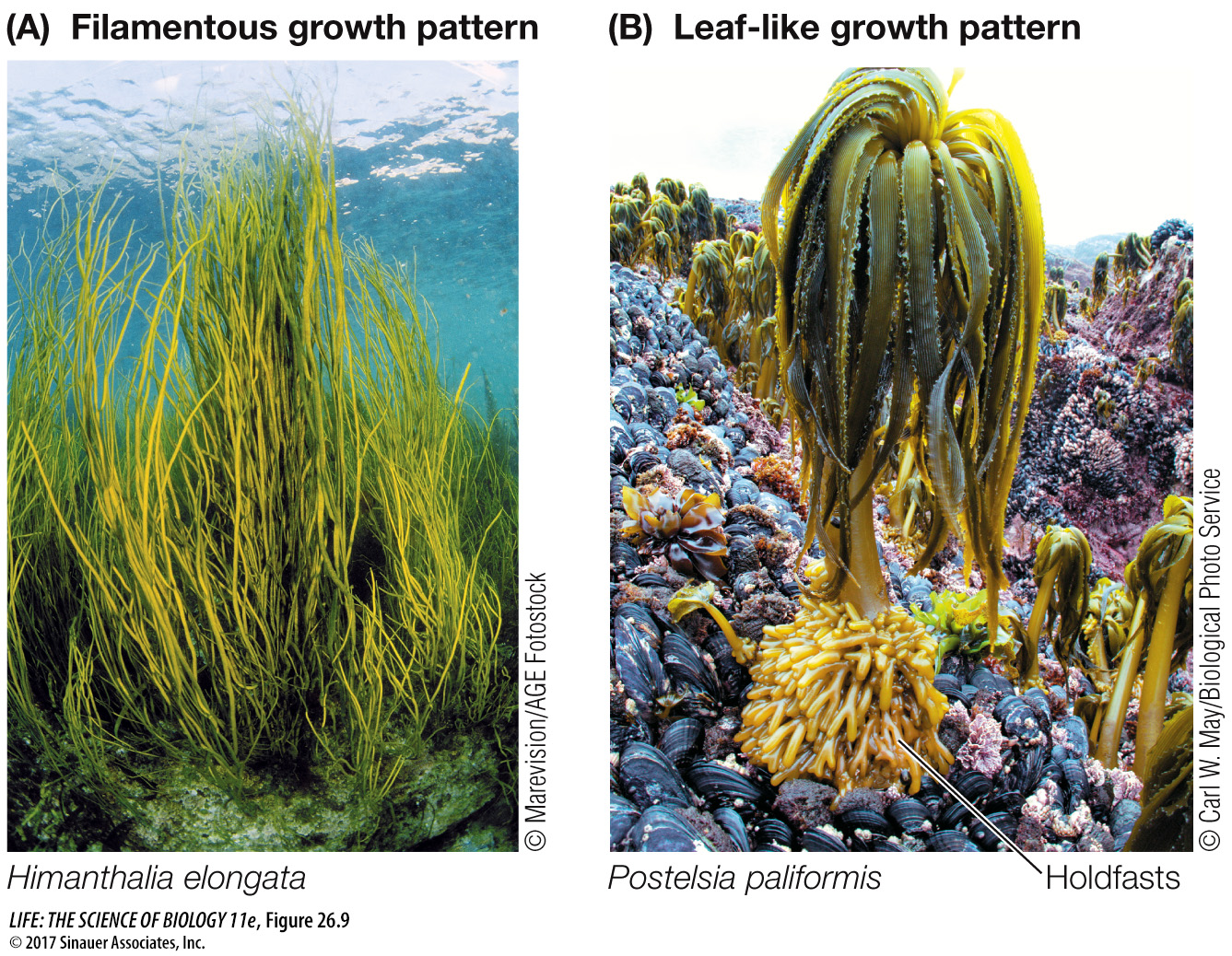

BROWN ALGAE The brown algae obtain their namesake color from the carotenoid fucoxanthin, which is abundant in their chloroplasts. The combination of this yellow-

Media Clip 26.3 A Kelp Forest

www.life11e.com/

The brown algae are almost exclusively marine. They are composed either of branched filaments (Figure 26.9A) or of leaflike growths (Figure 26.9B). Some float in the open ocean; the most famous example is the genus Sargassum, which forms dense mats in the Sargasso Sea in the mid-

560

OOMYCETES The oomycetes are the water molds and their terrestrial relatives. Water molds are filamentous and stationary. They are absorptive heterotrophs—that is, they secrete enzymes that digest large food molecules into smaller molecules that they can absorb. They are all aquatic and saprobic—meaning they feed on dead organic matter. If you have seen a whitish, cottony mold growing on dead fish or dead insects in water, it was probably a water mold of the common genus Saprolegnia (Figure 26.10).

Some other oomycetes, such as the downy mildews, are terrestrial. Although most of the terrestrial oomycetes are harmless or helpful decomposers of dead matter, a few are plant parasites that attack crops such as avocados, grapes, and potatoes.

Oomycetes were once classified as fungi. However, we now know that their similarity to fungi is only superficial, and that the oomycetes are more distantly related to the fungi than are many other eukaryote groups, including humans (see Figure 26.3). For example, the cell walls of oomycetes are typically made of cellulose, whereas those of fungi are made of chitin.