The sporophytes of nonvascular land plants are dependent on the gametophytes

In the nonvascular land plants, the conspicuous green structure visible to the naked eye is the gametophyte. The gametophyte is photosynthetic and is therefore nutritionally independent; the sporophyte may or may not be photosynthetic, but it is always nutritionally dependent on the gametophyte and remains permanently attached to it.

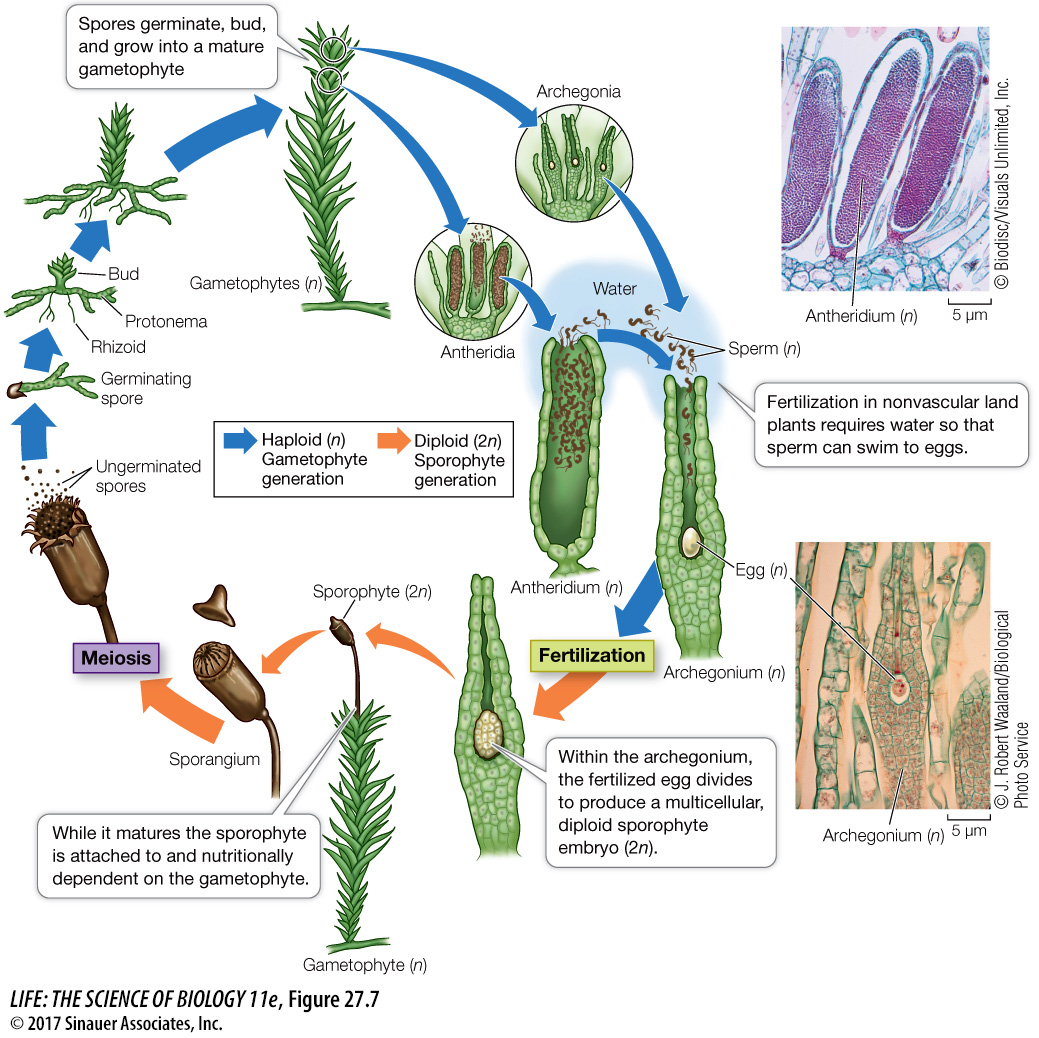

Figure 27.7 illustrates the life cycle of a moss, which is typical of the life cycles of nonvascular land plants. A sporophyte produces unicellular haploid spores as products of meiosis within a sporangium. When a spore germinates, it gives rise to a multicellular haploid gametophyte whose cells contain chloroplasts and are thus photosynthetic. Eventually gametes form within specialized sex organs, called the gametangia. The archegonium is a multicellular, flask-

580

Animation 27.1 Life Cycle of a Moss

www.life11e.com/

Media Clip 27.2 Nonvascular Plant Reproduction

www.life11e.com/

Once released from the antheridium, the sperm must swim or be splashed by raindrops to a nearby archegonium on the same or a neighboring plant—

581

Once sperm arrive at an egg, the nucleus of a sperm fuses with the egg nucleus to form a diploid zygote. Mitotic divisions of the zygote produce a multicellular, diploid sporophyte embryo. After the sporophyte grows out of the archegonium it produces a single sporangium, within which meiotic divisions produce spores and thus the next gametophyte generation.