Water and sugar transport mechanisms emerged in the mosses

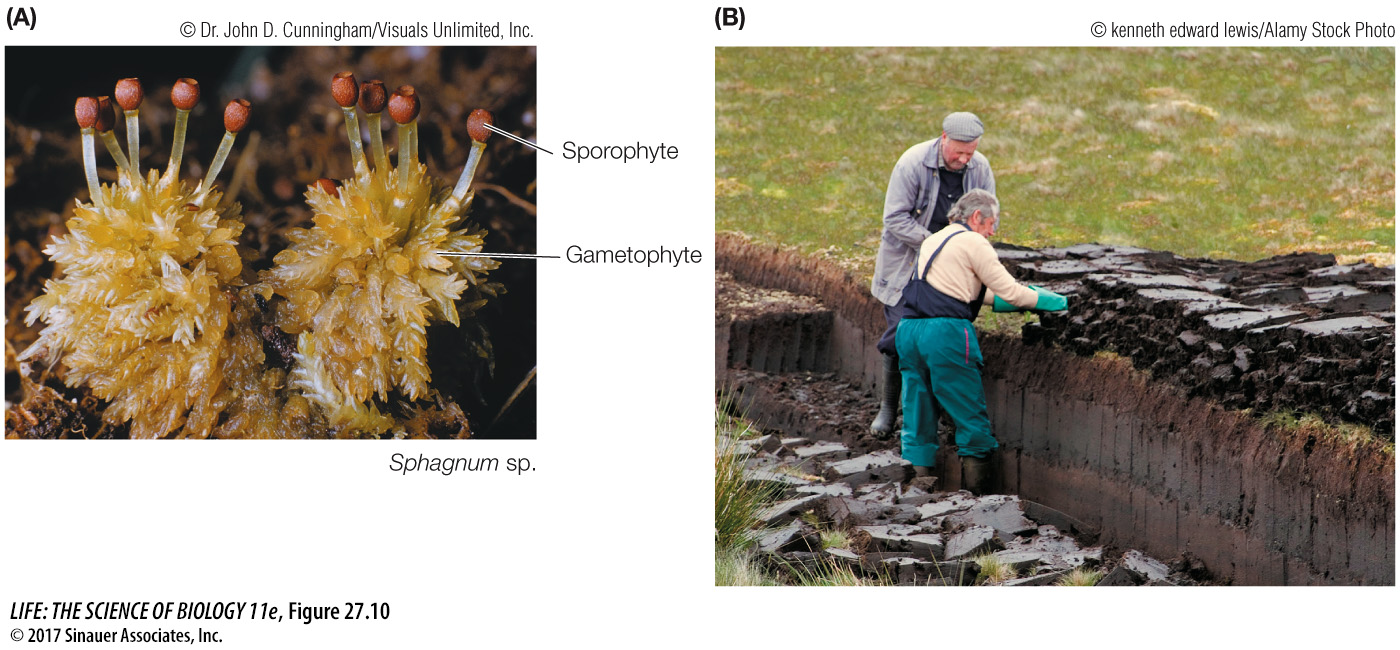

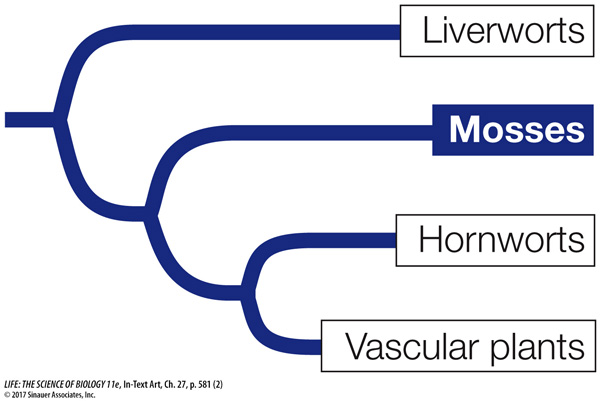

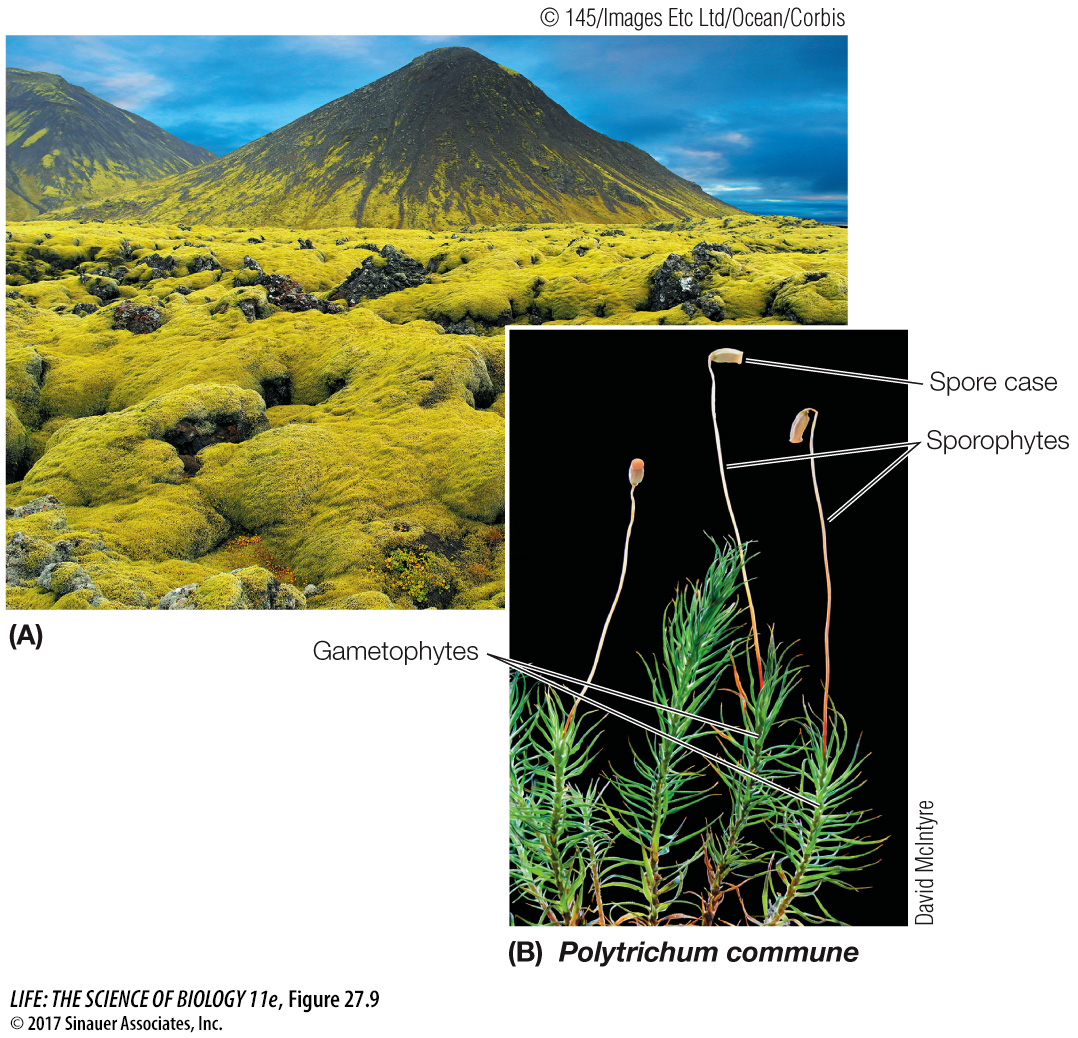

The most familiar of the nonvascular land plants are the mosses. These hardy little plants, of which there are about 15,000 species, are found in almost every terrestrial environment. They are often found on damp, cool ground, where they form thick mats (Figure 27.9). The mosses are the sister clade of the vascular plants plus the hornworts (see Figure 27.1B).

The mosses, along with the hornworts and vascular plants, share an advance over the liverworts in their adaptation to life on land: they have openings called stomata, which allow CO2 to enter the plant body and allow water and O2 to leave it. Stomata are a synapomorphy of mosses and all other land plants except liverworts.

In mosses, the gametophyte begins its development following spore germination as a branched, filamentous structure called a protonema (see Figure 27.7). Although the protonema looks a bit like a filamentous green alga, this structure is unique to the mosses. Some of the filaments contain chloroplasts and are photosynthetic; others, called rhizoids, are nonphotosynthetic and anchor the protonema to the substrate. After a period of linear growth, cells close to the tips of the photosynthetic filaments divide rapidly in three dimensions to form buds. The buds eventually develop a distinct tip, or apex, and produce the familiar leafy moss shoot with leaflike structures arranged spirally. These leafy shoots produce antheridia or archegonia (see Figure 27.7).

Some moss gametophytes are too large to transport enough water through their bodies solely by diffusion. Gametophytes and sporophytes of many mosses contain a type of cell called a hydroid, which dies and leaves a tiny channel through which water can travel. The hydroid is functionally similar to the tracheid, the characteristic water-

582

Mosses of the genus Sphagnum (Figure 27.10A) often grow in cool, swampy places, where the plants begin to decompose in water after they die. Rapidly growing upper layers of moss compress the deeper-