Vascular plants allowed herbivores to colonize the land

The initial absence of herbivores (plant-eating animals) on land helped make the first vascular plants successful. By the late Silurian period (about 425 mya), vascular plants were being preserved as fossils that we can study today. The proliferation of these plants made the terrestrial environment more hospitable to animals. Arthropods, vertebrates, and other animals moved onto land only after vascular plants became established there.

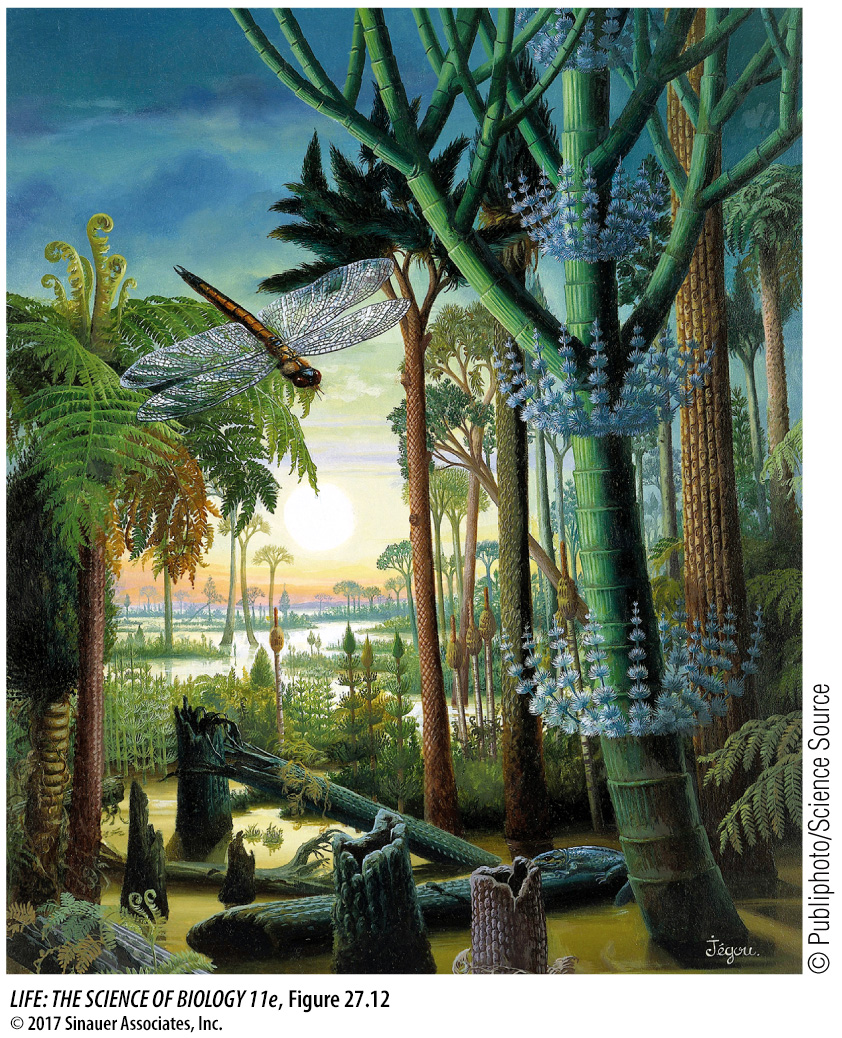

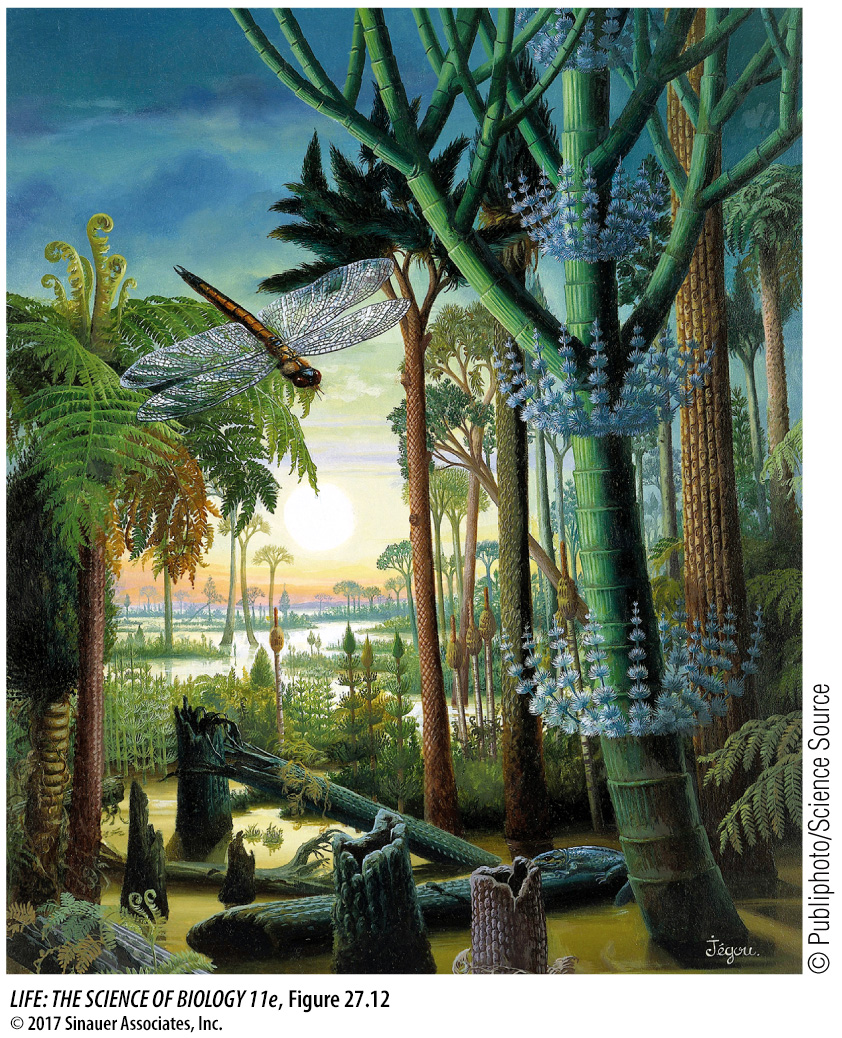

Trees of various kinds appeared in the Devonian period and dominated the landscape of the Carboniferous period (359–299 mya). Forests of lycophytes (club mosses) up to 40 meters tall, along with horsetails and tree ferns, flourished in the tropical swamps of what would become North America and Europe (Figure 27.12). Plant material from those forests sank into the swamps and was gradually covered by layers of sediment. Over millions of years, as the buried plant material was subjected to intense pressure and elevated temperatures, it was transformed into coal. Today that coal provides more than 40 percent of the electricity generated worldwide. The world’s coal deposits, although huge, are not infinite, and humans are burning coal deposits at a far faster rate than they were produced.

Figure 27.12 Artist’s Reconstruction of an Ancient Forest Forests of the Carboniferous period were characterized by abundant vascular plants such as club mosses, ferns, and horsetails, some of which reached heights of 40 meters. Huge flying insects (see the opening of Chapter 24) thrived in these forests, which are the source of modern coal deposits.

In the subsequent Permian period, when the continents came together to form Pangaea, the continental interior became warmer and drier. The 200-million-year reign of the lycophyte–fern forests came to an end as they were replaced by forests of early gymnosperms.