Conifers have cones and lack swimming sperm

The great Douglas fir and cedar forests found in the northwestern United States and the massive boreal forests of pine, fir, and spruce of northern Eurasia and North America, as well as on the upper slopes of mountain ranges everywhere, rank among the great forests of the world. All these trees belong to one group of gymnosperms: the conifers, or cone-

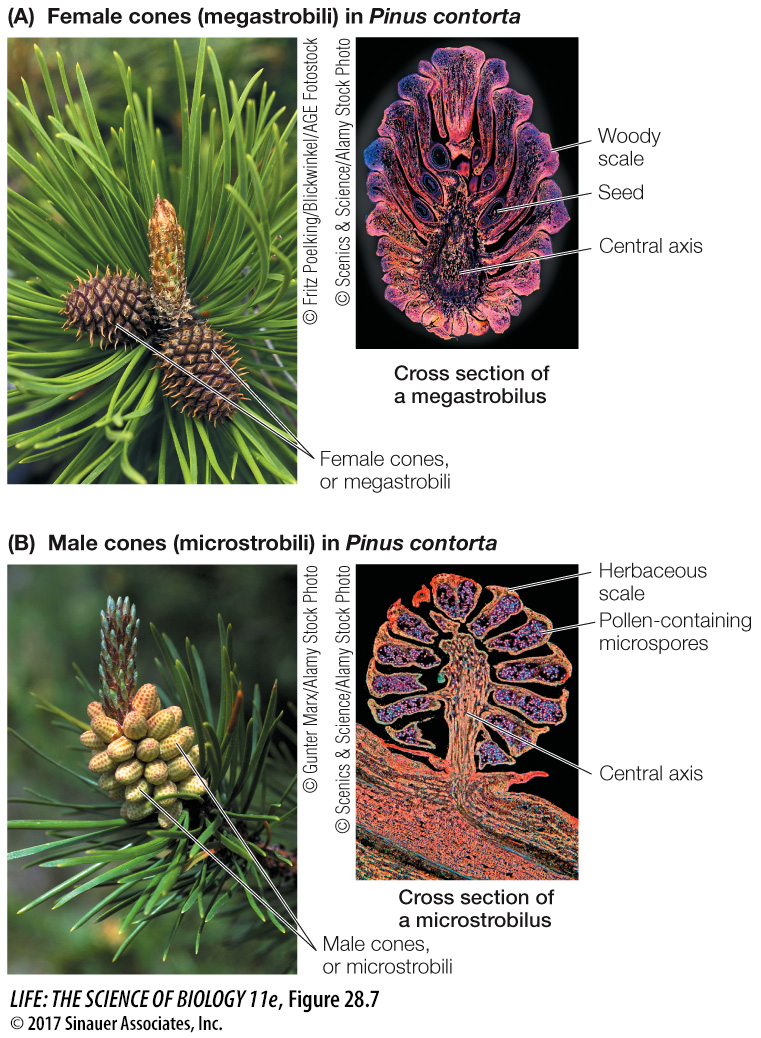

Male and female cones contain the reproductive structures of conifers. The female (seed-

599

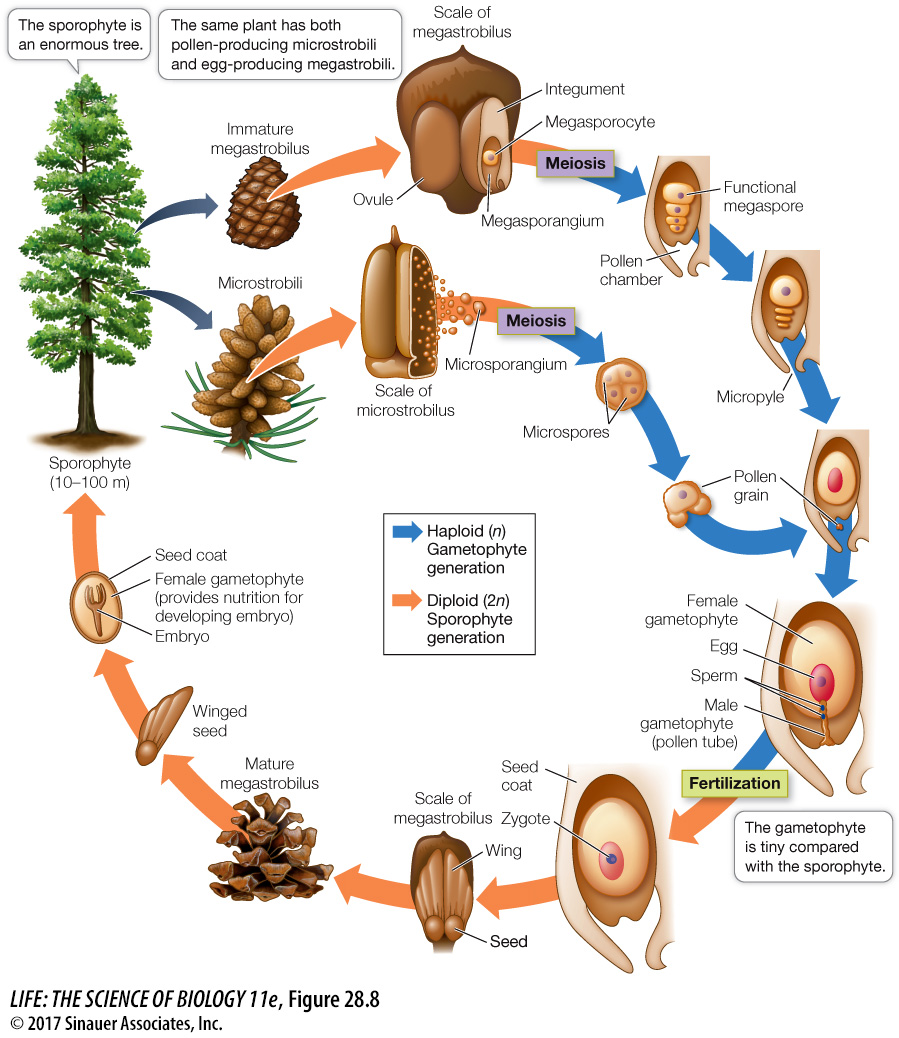

The life cycle of a pine illustrates reproduction in gymnosperms (Figure 28.8). As in other seed plants, conifers have male gametophytes in the form of pollen grains, which frees the plants completely from their dependence on liquid water for fertilization. Wind assists conifer pollen grains in their first stage of travel from the microstrobilus to the female gametophyte inside a cone. A pollen tube provides the sperm with the means for the last stage of travel by elongating through maternal sporophytic tissue. When the pollen tube reaches the female gametophyte, it releases two sperm, one of which degenerates after the other unites with the egg. Union of sperm and egg results in a zygote. Mitotic divisions and further development of the zygote result in an embryo.

The megasporangium, in which the female gametophyte will form, is enclosed in a layer of sporophytic tissue—

Most conifer ovules, which will develop into seeds after fertilization, are borne exposed on the upper surfaces of the scales of the megastrobilus. The only protection of the ovules comes from the scales, which are tightly pressed against one another within the cone. Some pines, such as the lodgepole pine, have tightly closed cones that are sealed with resin. Fire is needed to melt the resin and open the cones to release the seeds. These species are said to be fire-

About half of all conifer species have soft, fleshy tissues that envelop their seeds. Some of these are fleshy, fruitlike cones, as in junipers. Others are fruitlike extensions of the seeds, called arils, as in yews. These tissues, although often mistaken for “berries,” are not true fruits. As you will see in the next section, true fruits are the plant’s ripened ovaries, which are absent in gymnosperms. Nonetheless, the fleshy tissues that surround the seeds of many conifers serve a similar purpose as that of the fruits of flowering plants, acting as an enticement for seed-

600

Animation 28.1 Life Cycle of a Conifer

www.life11e.com/

Activity 28.2 Life Cycle of a Conifer

www.life11e.com/

601