The sexual reproductive structure of sac fungi is the ascus

The sac fungi (Ascomycota) are a large and diverse group of fungi found in marine, freshwater, and terrestrial habitats. There are approximately 64,000 known species, nearly half of which are the fungal partners in lichens. The hyphae of sac fungi are segmented by more or less regularly spaced septa. A pore in each septum permits extensive movement of cytoplasm and organelles (including nuclei) from one segment to the next.

627

Sac fungi are distinguished by the production of sacs called asci (singular ascus), which at maturity contain sexually produced haploid ascospores (see Figure 29.17A). The ascus is the characteristic sexual reproductive structure of the sac fungi. In the past, the sac fungi were classified on the basis of whether or not the asci are contained within a specialized fruiting structure known as an ascoma (plural ascomata) and on differences in the morphology of that fruiting structure. DNA sequence analyses have resulted in a revision of these traditional groupings, however.

SAC FUNGUS YEASTS Some species of sac fungi are unicellular yeasts. The 1,000 or so species in this group are among the most important domesticated fungi. Perhaps the best known is baker’s, or brewer’s, yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae; see Figure 29.2 and Key Concept 29.4), which metabolizes glucose obtained from its environment into ethanol and carbon dioxide by fermentation. Other sac fungus yeasts live on fruits such as figs and grapes and play an important role in the making of wine. Many others are associated with insects. In the guts of some insects, they provide enzymes that break down materials that are otherwise difficult for the insects to digest, especially cellulose.

Sac fungus yeasts reproduce asexually by budding. Sexual reproduction takes place when two adjacent haploid cells of dissimilar mating types fuse. In some species, the resulting zygote buds to form a diploid cell population. In others, the zygote nucleus undergoes meiosis immediately. When this happens, the entire cell becomes an ascus. Depending on whether the products of meiosis then undergo mitosis, a yeast ascus contains either eight or four ascospores, which germinate to become haploid cells. The sac fungus yeasts have lost the dikaryon stage.

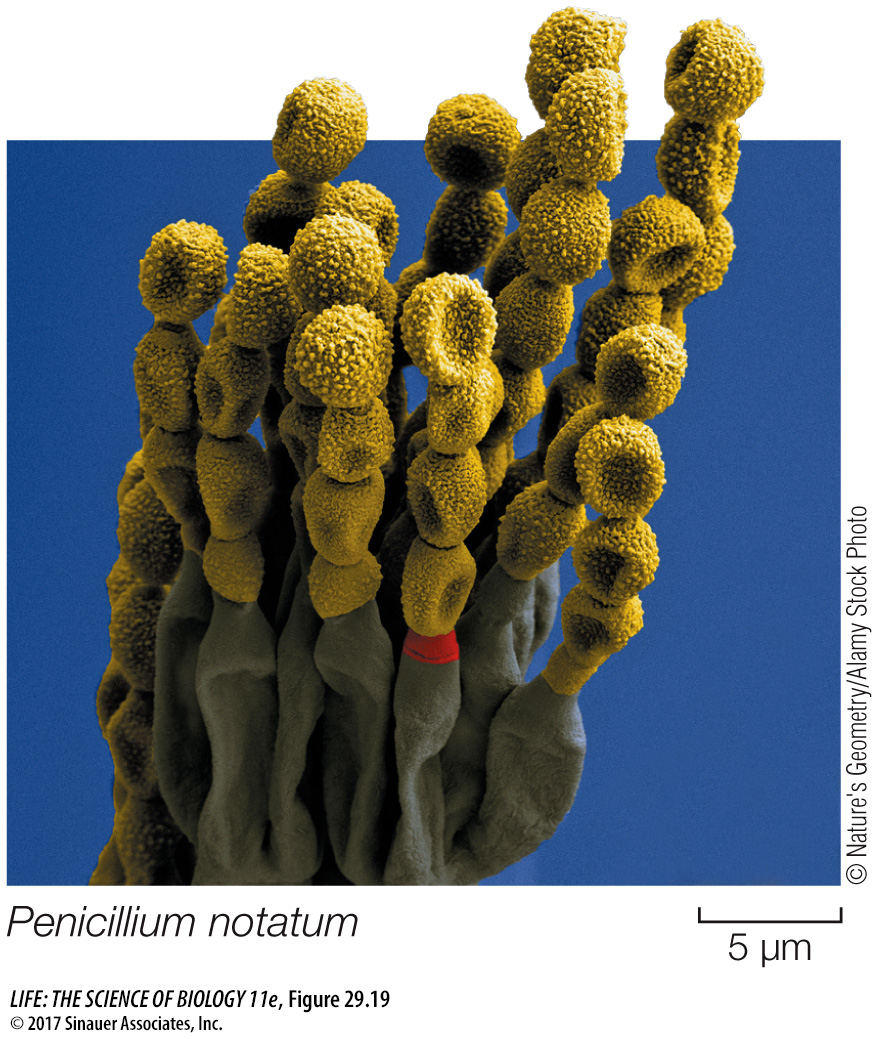

FILAMENTOUS SAC FUNGI Most sac fungi are filamentous species, such as the cup fungi (Figure 29.18), in which the ascomata are cup-

The sexual reproductive cycle of filamentous sac fungi includes the formation of a dikaryon, although this stage is relatively brief compared with that in club fungi. Many filamentous sac fungi form multinucleate mating structures (see Figure 29.17A). Mating structures of two different mating types fuse and produce a dikaryotic mycelium, containing nuclei from both mating types. The dikaryotic mycelium often forms a cup-

The sac fungi also include many of the filamentous fungi known as molds. Molds consist of filamentous hyphae that do not form large ascomata, although they can still produce asci and ascospores. Many molds are parasites of flowering plants. Chestnut blight and Dutch elm disease are both caused by molds. The chestnut blight fungus, which was introduced to the United States in the 1890s, had destroyed the American chestnut as a commercial species by 1940. Before the blight, this species accounted for more than half the trees in the eastern North American forests. Another familiar story is that of the American elm. Sometime before 1930, the Dutch elm disease fungus (first discovered in the Netherlands, but native to Asia) was introduced into the United States on infected elm logs from Europe. Spreading rapidly—

628

Other plant pathogens among the sac fungi include the powdery mildews that infect cereal crops, lilacs, and roses, among many other plants. Mildews can be a serious problem to farmers and gardeners, and a great deal of research has focused on ways to control these agricultural pests.

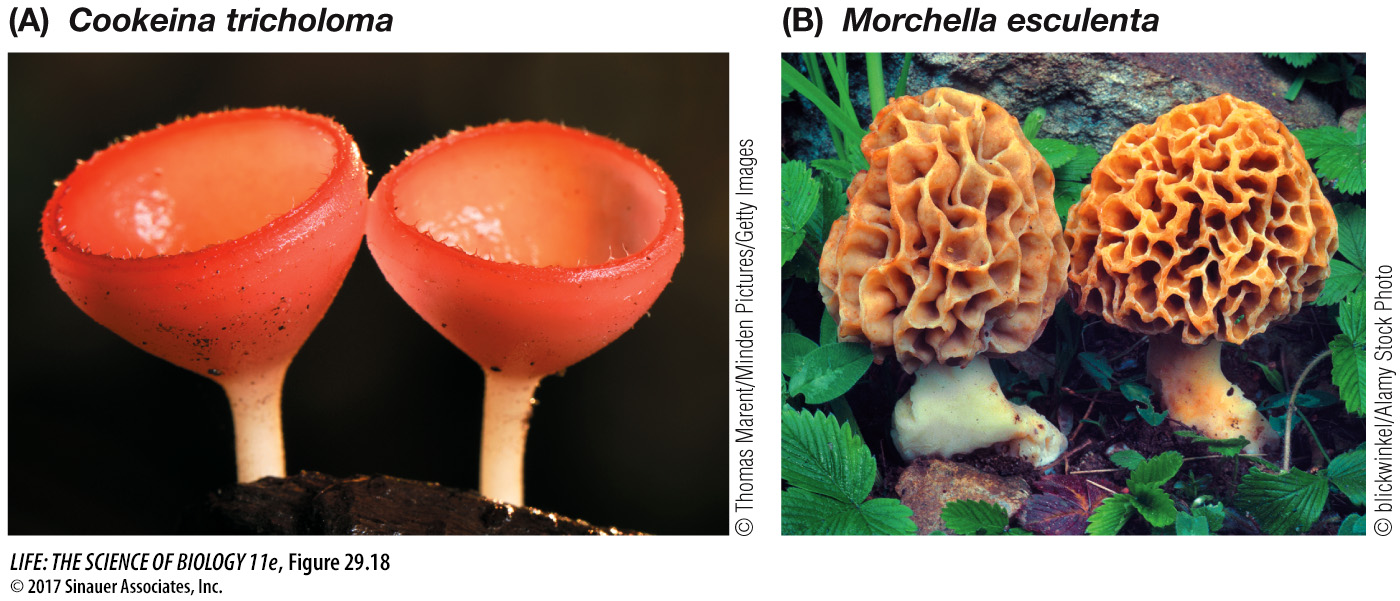

The filamentous sac fungi can also reproduce asexually by means of conidia that form at the tips of specialized hyphae (Figure 29.19). Small chains of conidia are produced by the millions and can survive for weeks in nature. The conidia are often what give molds their characteristic colors.