No life cycle can maximize all benefits

A common saying, “a jack-of-all-trades is master of none,” suggests why there are constraints on the evolution of life cycles. The characteristics an animal has in any one life cycle stage may improve its performance in one activity but reduce its performance in another—a situation known as a trade-off. An animal that is good at filtering small food items from the water, for example, is unlikely to be good at capturing large prey. Similarly, energy devoted to building protective structures such as shells cannot be used for growth.

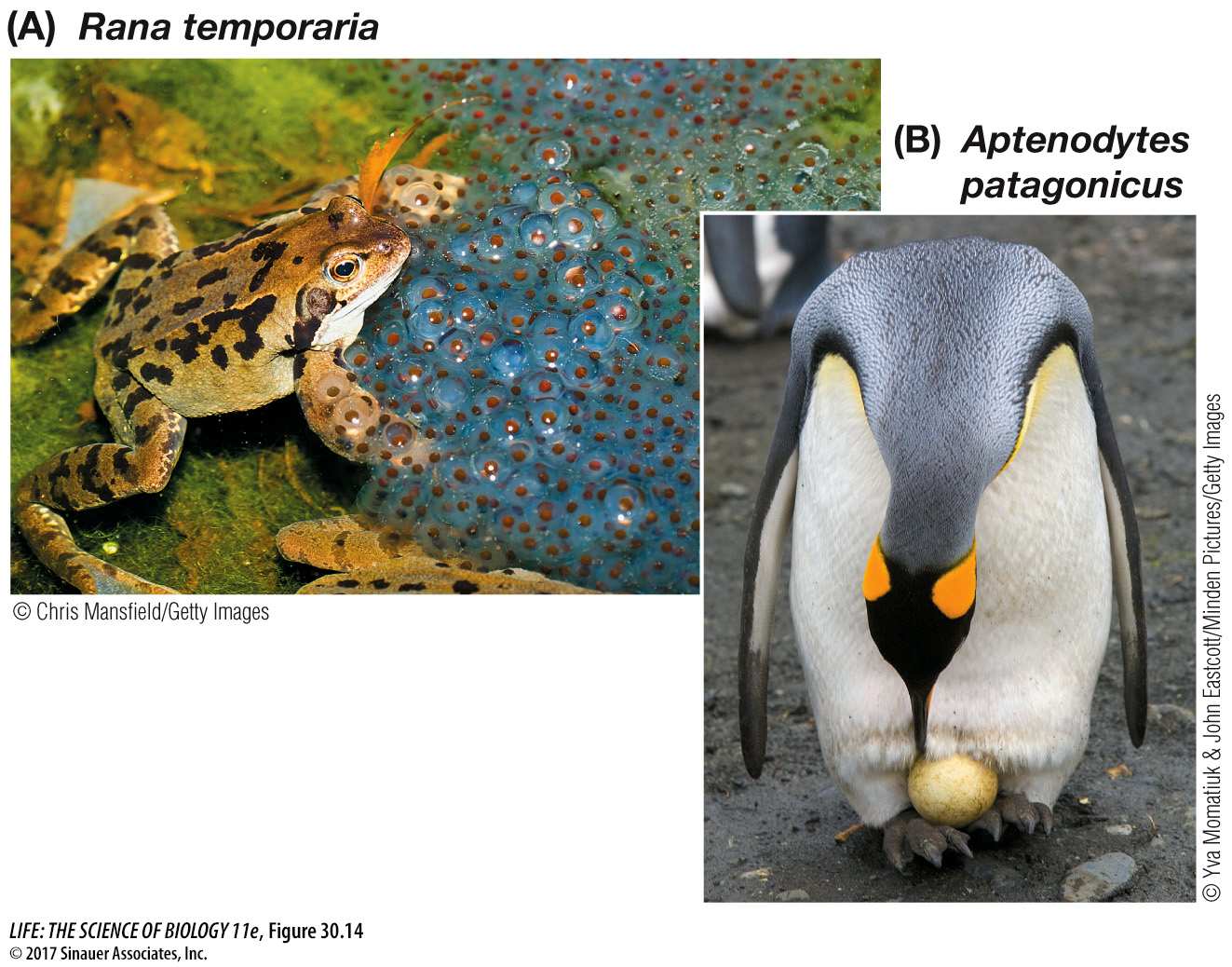

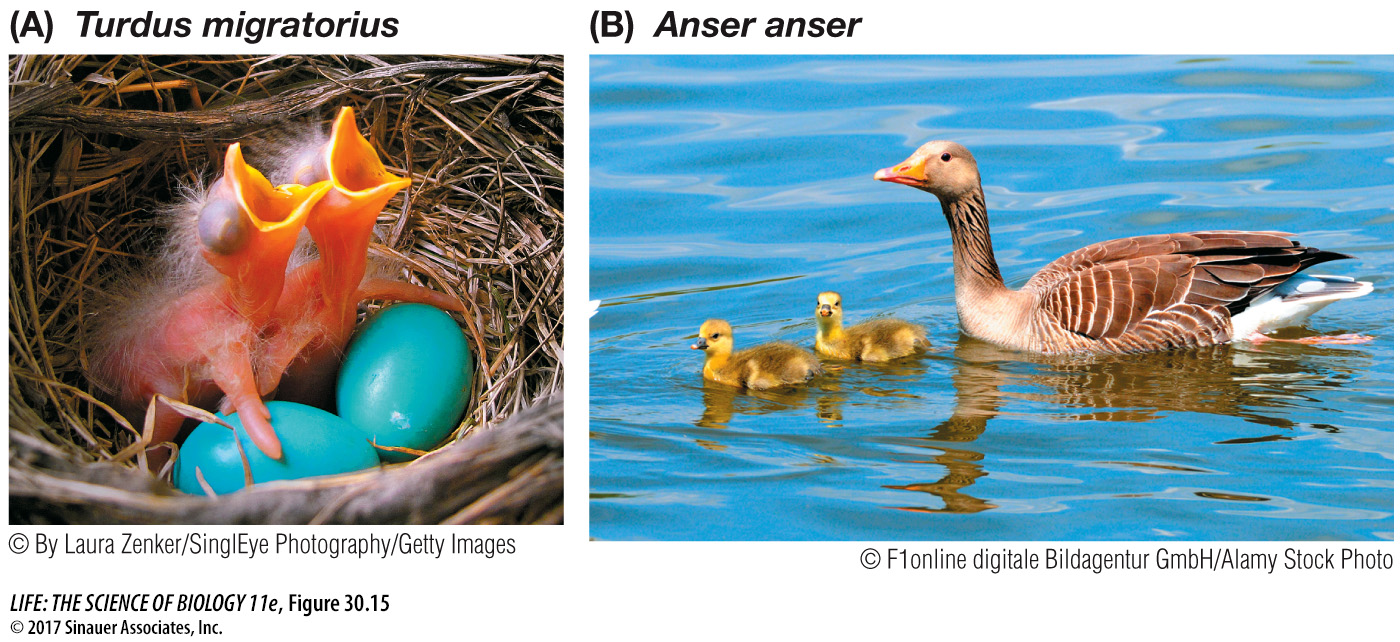

Some major trade-offs can be seen in animal reproduction. Some animals produce large numbers of small eggs, each with a small energy store (Figure 30.14A). Other animals produce a small number of large eggs, each with a large energy store (Figure 30.14B). With a fixed amount of energy available for reproduction, a female animal can produce many small eggs or a few large eggs, but she cannot produce many large eggs. Thus there is a trade-off between the number of offspring produced and the energy resources each offspring receives from its mother.

Figure 30.14 Many Small or Few Large Allocation of energy to eggs requires trade-offs. (A) This European common frog has divided her reproductive energy among a large number of small eggs. (B) This king penguin has invested all of her reproductive energy in one large egg.

Question

Q: What are the respective advantages and disadvantages of these two reproductive strategies?

Producing many small eggs allows a species to rapidly expand its population size under favorable environmental conditions. However, when conditions are less favorable, the low parental investment in each egg means that very few, if any, offspring are likely to survive. In contrast, producing one large egg with high parental investment greatly increases the likelihood of each offspring surviving, but many fewer offspring can be produced, so populations cannot change rapidly to take advantage of temporarily favorable conditions.

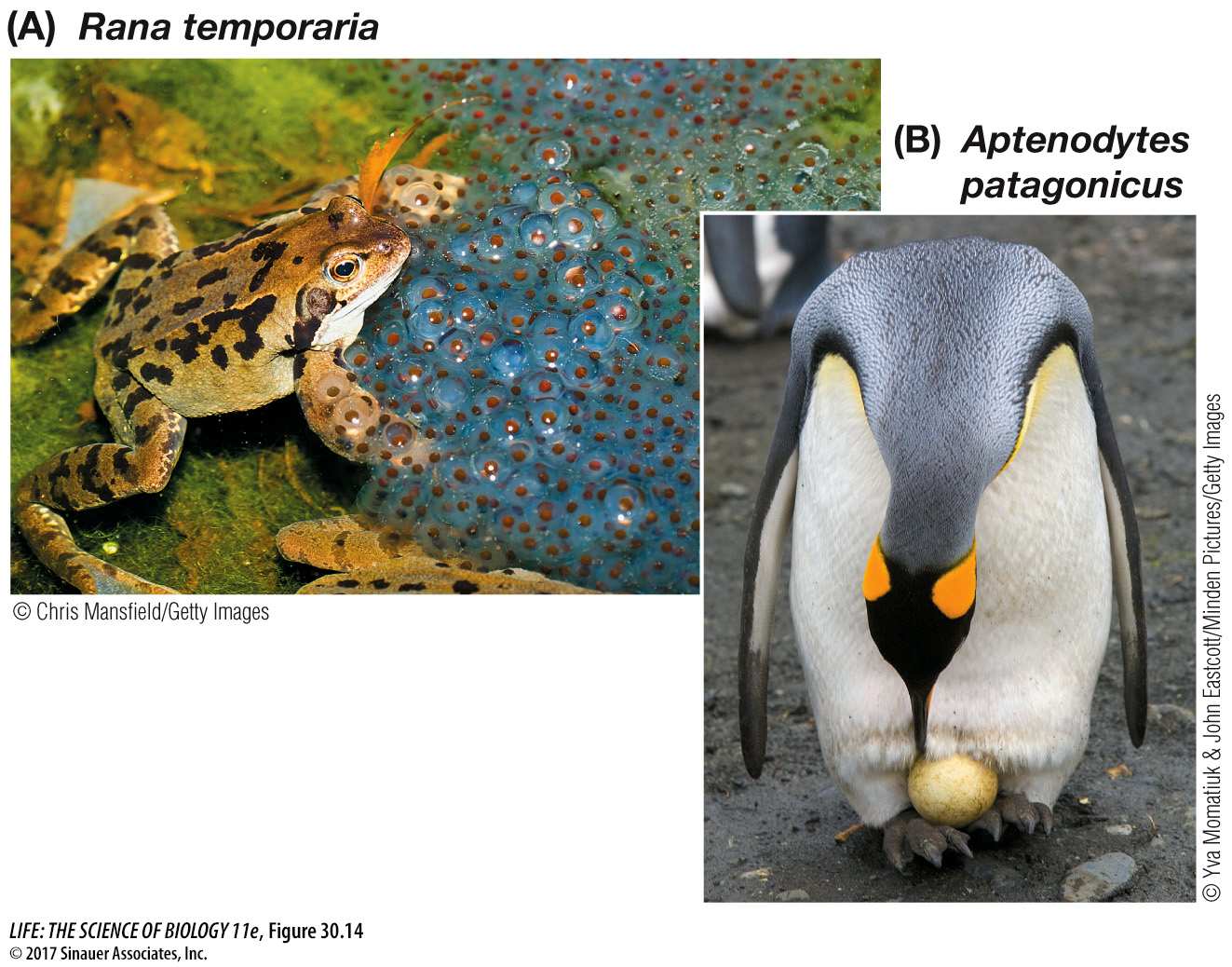

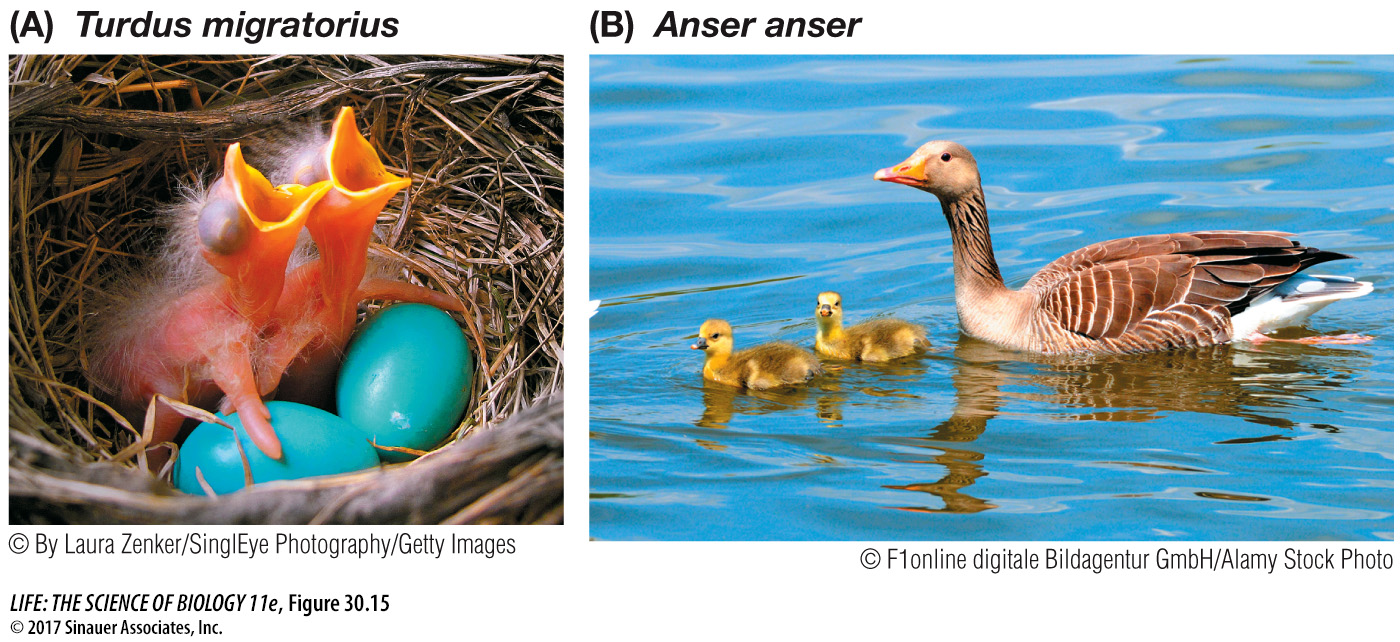

The larger the energy store in an egg, the longer an offspring can develop before it must either find its own food or be fed by its parents. Birds of all species lay relatively small numbers of relatively large eggs, but incubation periods vary. In some species, eggs hatch when the young are still helpless (Figure 30.15A). Such altricial young must be fed and cared for until they can feed themselves; parents can provide for only a small number of altricial offspring. In contrast, some bird species incubate their eggs longer, and the hatchlings are developed to the point that they are able to forage for themselves almost immediately (Figure 30.15B). The young of such species are called precocial.

Figure 30.15 Helpless or Independent (A) The altricial young of the common robin are essentially helpless when they hatch. Their parents feed and care for them for several weeks. (B) Graylag goose hatchlings are precocial, ready to swim and feed independently almost immediately after hatching.