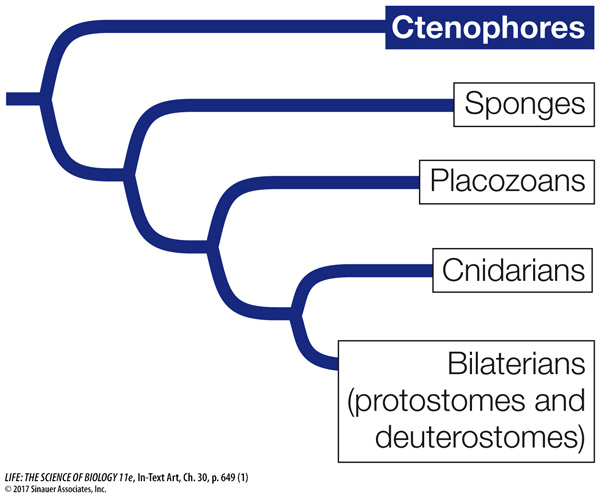

Ctenophores are the sister group of all other animals

Ctenophores, also known as comb jellies, were until recently thought to be most closely related to the cnidarians (jellyfish, corals, and their relatives). But ctenophores lack most of the Hox genes and many other genes found in all other animals, and recent studies of their genomes provide strong evidence that ctenophores were the earliest lineage to split from the remaining animals (Investigating Life: Reconstructing Animal Phylogeny from Protein-Coding Genes). This position in the animal tree does not imply that ctenophores look anything like the ancestral animal, however. All living ctenophores are quite closely related to one another, and they have been evolving for as long as all other animal lineages—

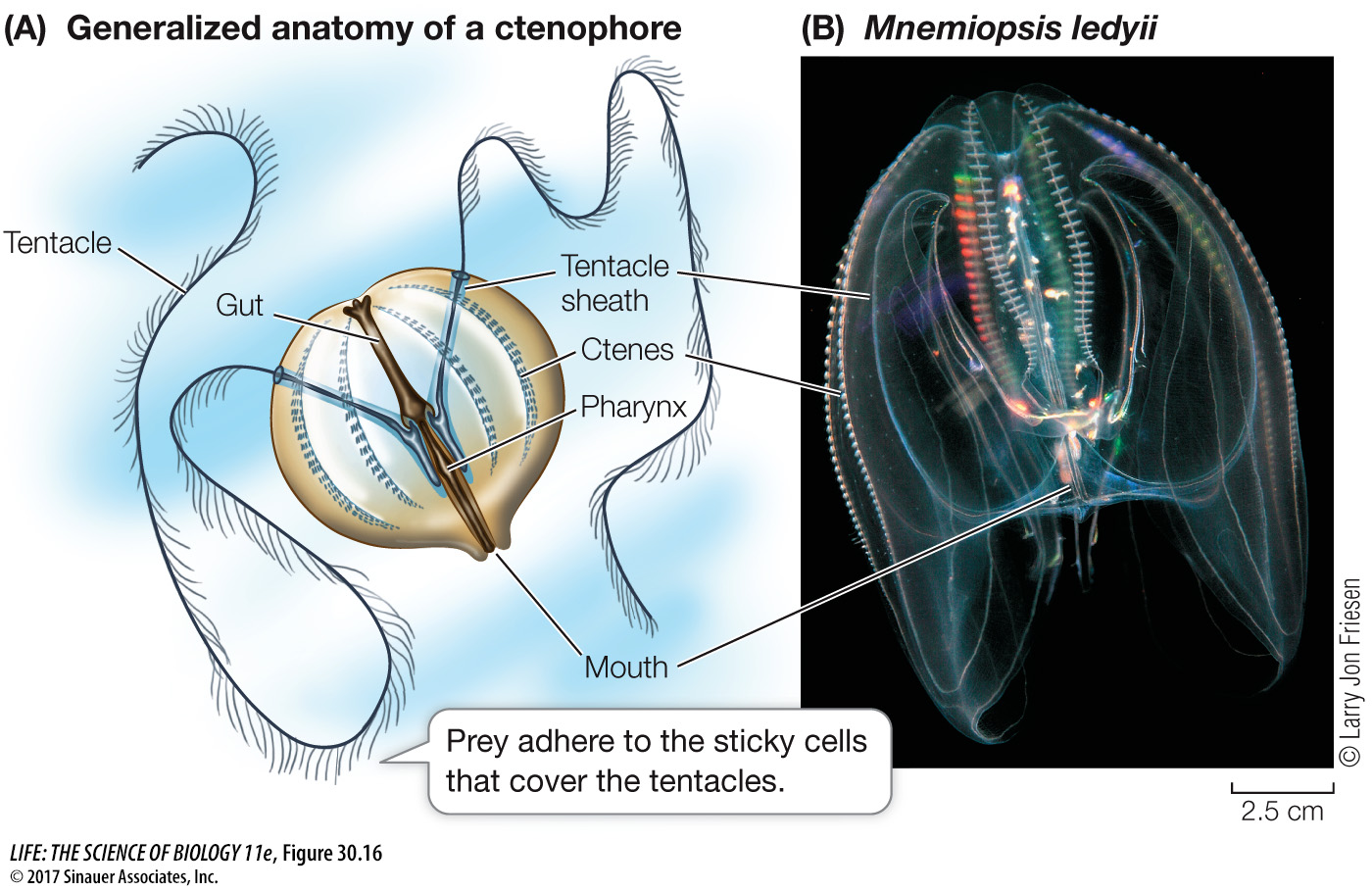

Ctenophores have a radially symmetrical, diploblastic body plan. The two cell layers are separated by an inert, gelatinous extracellular matrix called mesoglea. Ctenophores, unlike sponges, have a complete gut: food enters through a mouth, and wastes are eliminated through two anal pores.

Ctenophores move by beating cilia rather than by muscular contractions. Most of the 250 known species have eight comblike rows of cilia-

The feeding tentacles of ctenophores are covered with cells that discharge adhesive material when they contact prey. After capturing its prey, a ctenophore retracts its tentacles to bring the food to its mouth. In some species, the entire surface of the body is coated with sticky mucus that captures prey. Most ctenophores eat small planktonic organisms, although some eat other ctenophores. They are common in open seas and can become abundant in coastal bays, where large populations of ctenophores may inhibit the growth of other organisms.

Ctenophore life cycles are uncomplicated. Gametes are released into the gut and discharged through the mouth or the anal pores. Fertilization takes place in open seawater. In nearly all species, the fertilized egg develops directly into a miniature ctenophore, which gradually grows into an adult.

Media Clip 30.4 Ctenophores

www.life11e.com/