Cnidarians are specialized predators

652

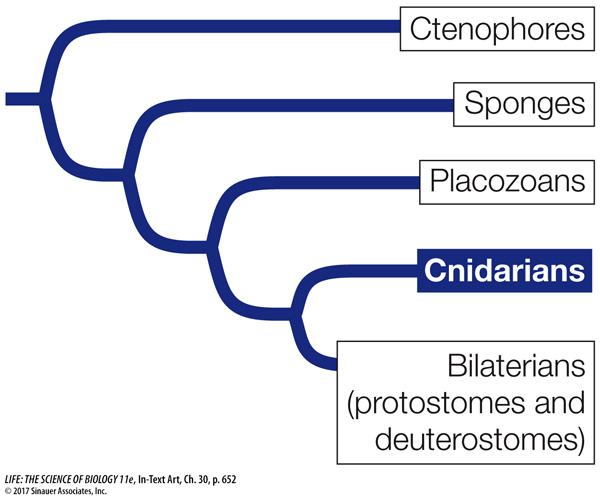

The cnidarians (jellyfish, sea anemones, corals, and hydrozoans) make up the largest and most diverse group of non-

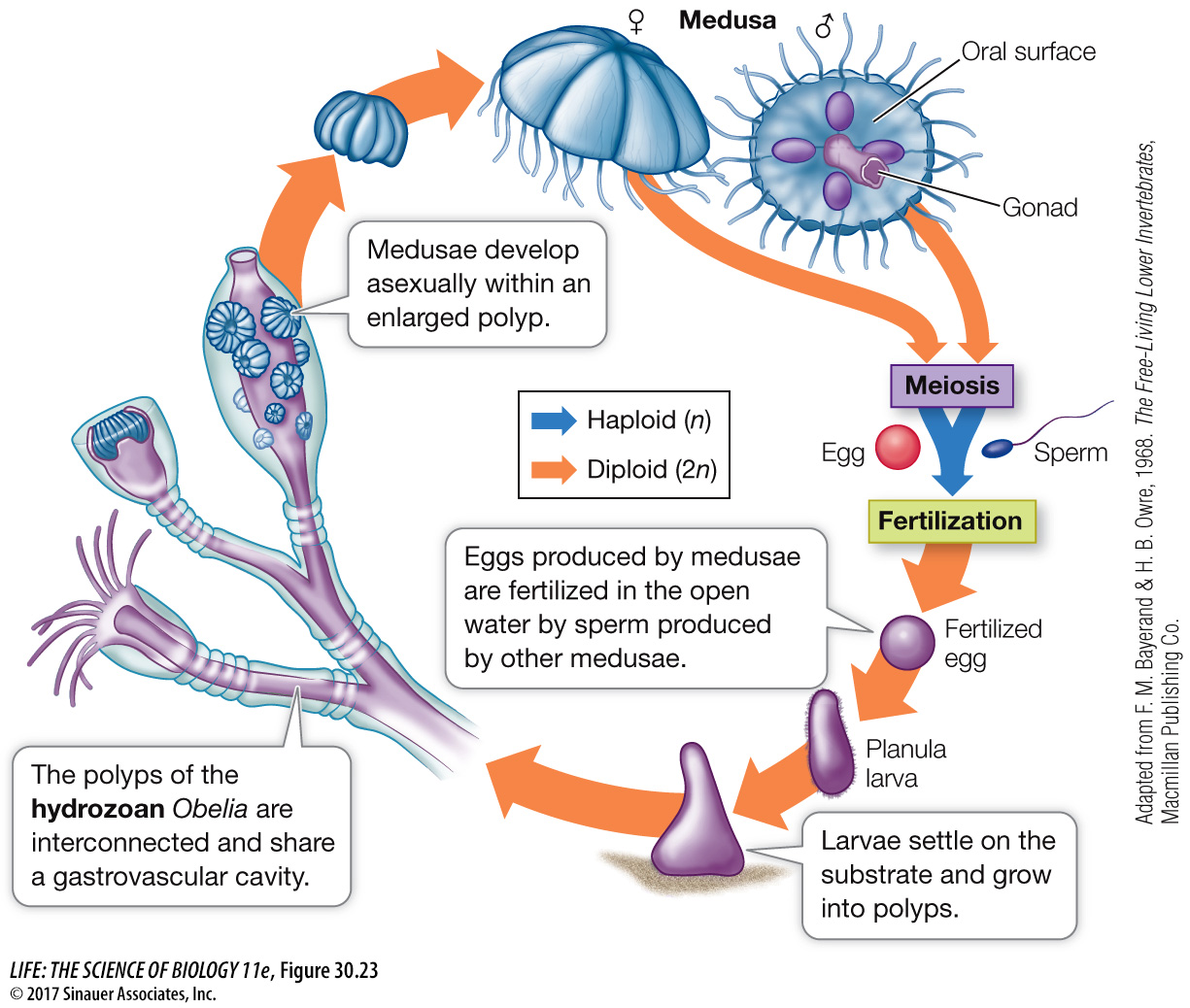

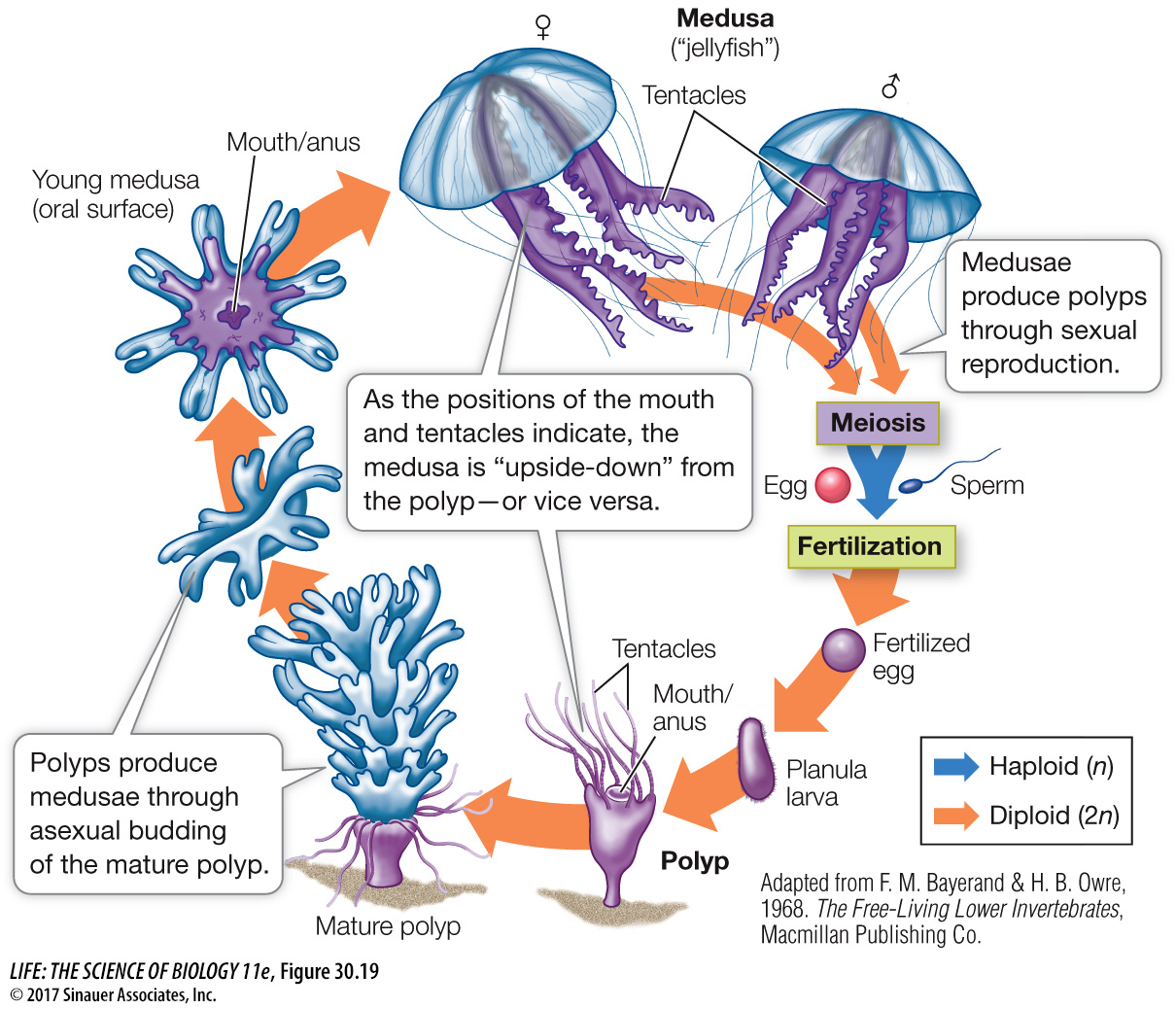

The life cycle of many cnidarians has two distinct stages, one sessile and the other motile (Figure 30.19), although one or the other of these stages is absent in some groups. In the sessile polyp stage, a cylindrical stalk attaches the animal to the substrate. The motile medusa (plural medusae) is a free-

Animation 30.1 Life Cycle of a Cnidarian

www.life11e.com/

Mature polyps produce medusae by asexual budding. Medusae then reproduce sexually, producing eggs or sperm by meiosis and releasing the gametes into the water. A fertilized egg develops into a free-

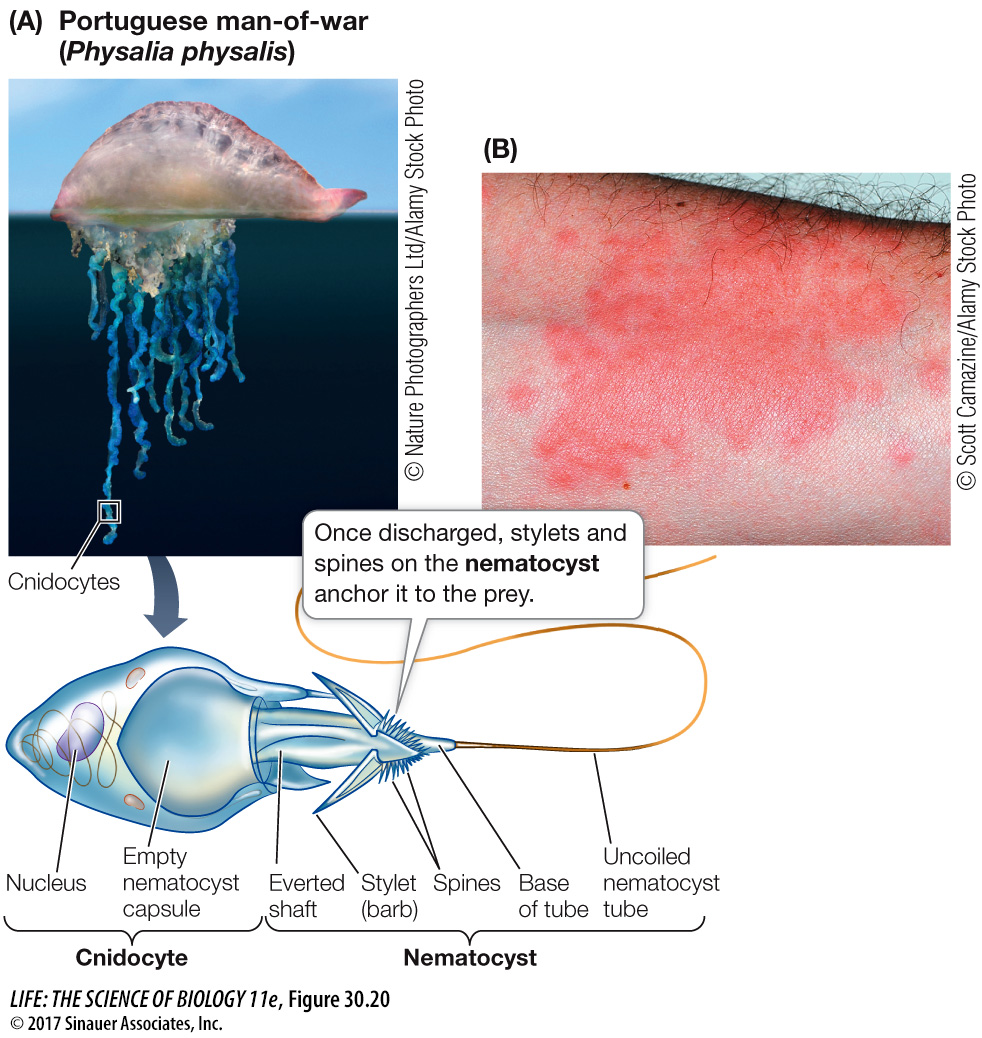

Cnidarians are specialized predators adapted for capturing and subduing relatively large and complex prey. As we noted earlier in discussing ctenophores, recent genome studies suggest that the nerve nets found in cnidarians are largely independently derived from those found in ctenophores, as well as from the nervous systems found in bilaterians. The tentacles of cnidarians are covered with specialized cells that contain stinging organelles called nematocysts, which inject toxins into their prey (Figure 30.20). Some cnidarians, including many corals and anemones, gain additional nutrition from photosynthetic endosymbionts that live in their tissues.

Cnidarians have cells containing muscle fibers whose contractions enable the animals to move, as well as simple nerve nets that integrate the body’s activities. Their bodies also contain specialized structural molecules (collagen, actin, and myosin). Yet cnidarians, like ctenophores, are largely made up of inert mesoglea. Most species have low metabolic rates and can survive in environments where they encounter prey only infrequently.

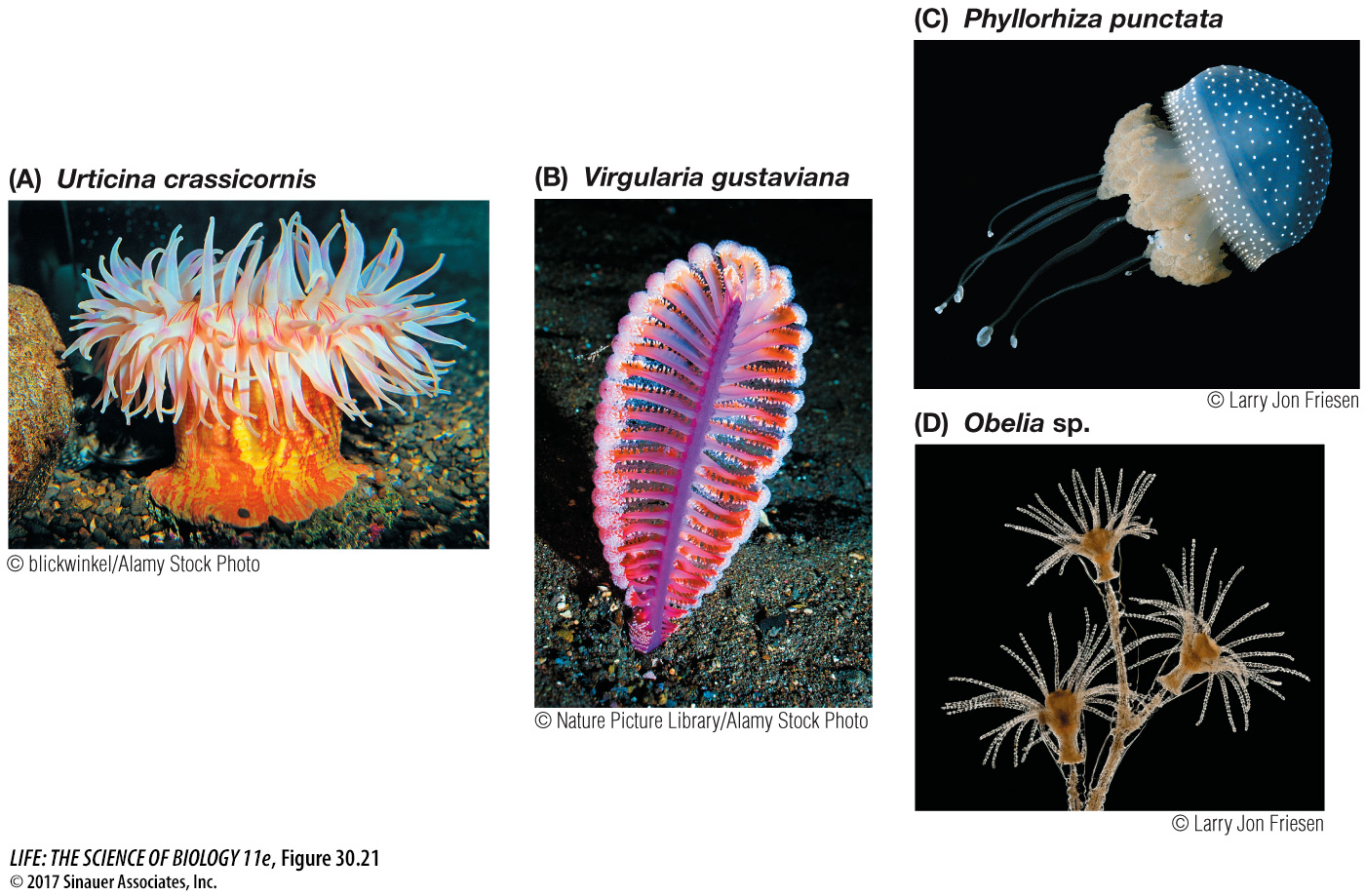

Of the roughly 12,500 living cnidarian species, all but a few live in the oceans (Figure 30.21). The smallest cnidarians can barely be seen without a microscope. One small group, known as myxozoans, consists of tiny parasites, usually with a two-

Media Clip 30.5 Stunning Siphonophore: Colonial Hydrozoans

www.life11e.com/

653

ANTHOZOANS Members of the anthozoan clade include sea anemones, sea pens, and corals. Sea anemones (see Figure 30.21A), all of which are solitary, are widespread in both warm and cold ocean waters. Sea pens (see Figure 30.21B), by contrast, are colonial. Each colony consists of two or more different kinds of polyps. The primary polyp has a lower portion anchored in the bottom sediment and a branched upper portion that projects above the substrate. Along the upper portion, the primary polyp produces smaller secondary polyps by budding. Some of these secondary polyps differentiate into feeding polyps; in some species, other secondary polyps differentiate to circulate water through the colony.

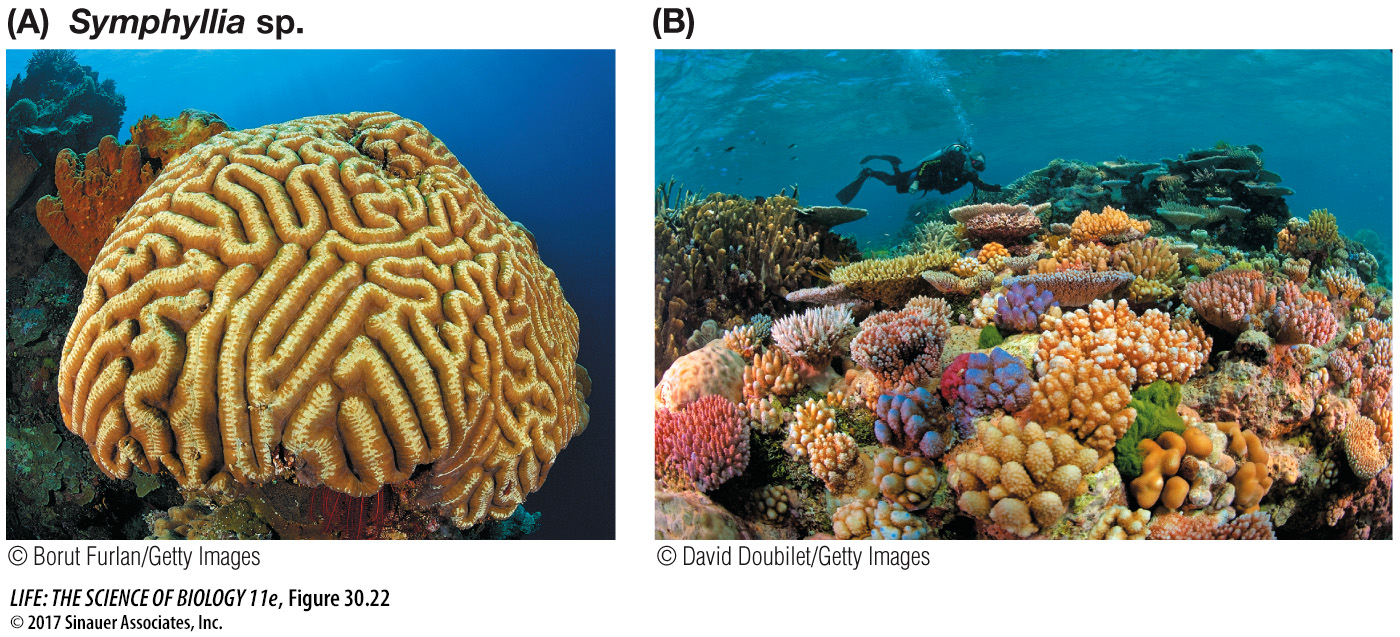

The common names of coral groups—

654

Corals flourish at shallow depths in clear, nutrient-

Coral reefs throughout the world are threatened by rising CO2 levels (which result in increased ocean temperatures and acidification of ocean waters through the formation of carbonic acid). Polluted runoff from development on adjacent shorelines is an additional threat to corals. Warmer temperatures lead to the loss of *coral endosymbionts (known as coral bleaching), and acidification can cause coral skeletons to dissolve. An overabundance of nitrogen from fertilizer in runoff is advantageous to algae, which overgrow and eventually smother the corals.

*connect the concepts Investigating Life: Can Corals Reaquire Dinoflagellate Endosymbionts Lost to Bleaching? in Chapter 26 describes an experiment in which coral endosymbionts were lost and replaced by new endosymbionts in response to changing environmental conditions.

SCYPHOZOANS The several hundred species of scyphozoans are all marine. The mesoglea of their medusae is thick and firm, giving rise to their common name of jellyfish (or sea jellies). The medusa rather than the polyp dominates the life cycle of scyphozoans. An individual medusa is male or female, releasing eggs or sperm into the open sea. A fertilized egg develops into a small planula larva that quickly settles on a substrate and develops into a small polyp. This polyp feeds and grows and may produce additional polyps by budding. After a period of growth, the polyp begins to bud off small medusae, which feed, grow, and transform into adult medusae (see Figures 30.19 and 30.21C).

HYDROZOANS The polyp typically dominates the life cycle of hydrozoans, but some species have only medusae and others have only polyps. Most hydrozoans are colonial. A single planula larva eventually gives rise to a colony of many polyps, all interconnected and sharing a continuous gastrovascular cavity (Figure 30.23). Within such a colony, some polyps have tentacles with many nematocysts; they capture prey for the colony. Other individuals lack tentacles and are unable to feed, but are specialized for the asexual production of medusae. Still others are fingerlike and defend the colony with their nematocysts.

655