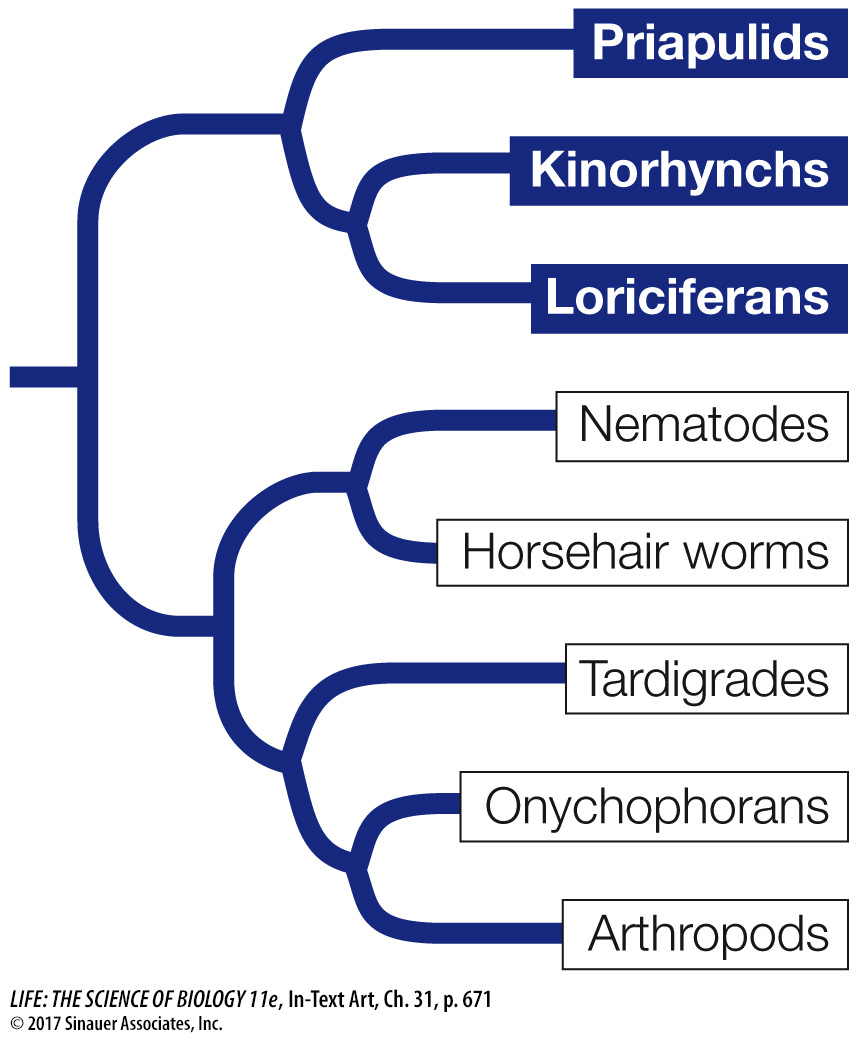

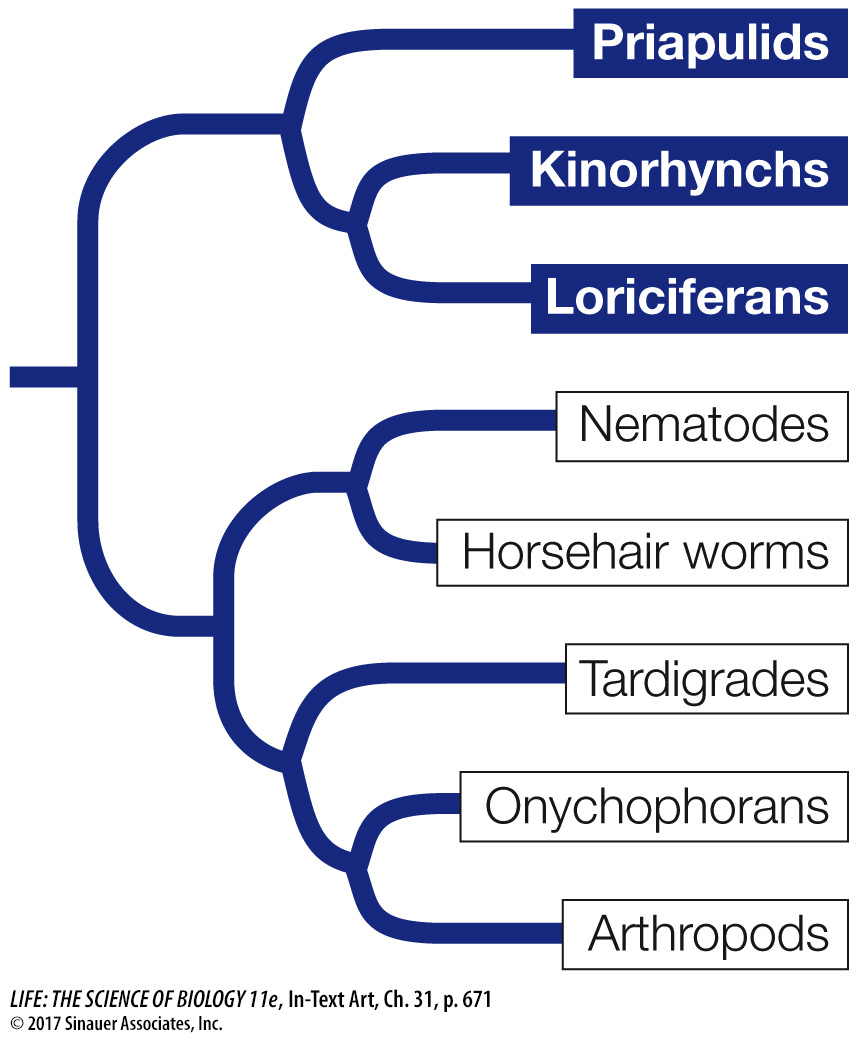

Several marine ecdysozoan groups have relatively few species

Members of several species-poor groups of wormlike marine ecdysozoans—the priapulids, kinorhynchs, and loriciferans—have relatively thin cuticles that are molted periodically as the animals grow to full size. Embryos of a fossil species related to these ecdysozoans have been discovered in sediments laid down in China about 500 million years ago. This remarkable discovery shows that the ancestors of these animals developed directly from an egg to the adult form, as most of their modern descendants do.

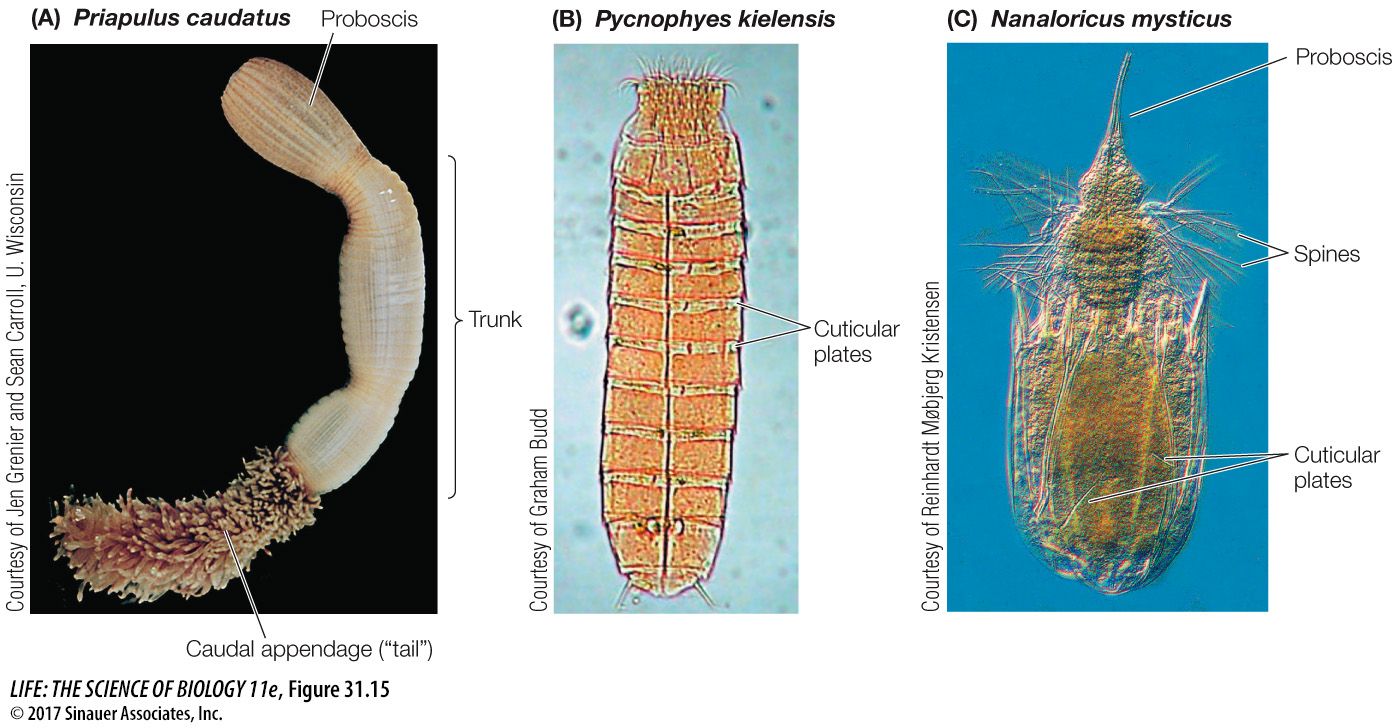

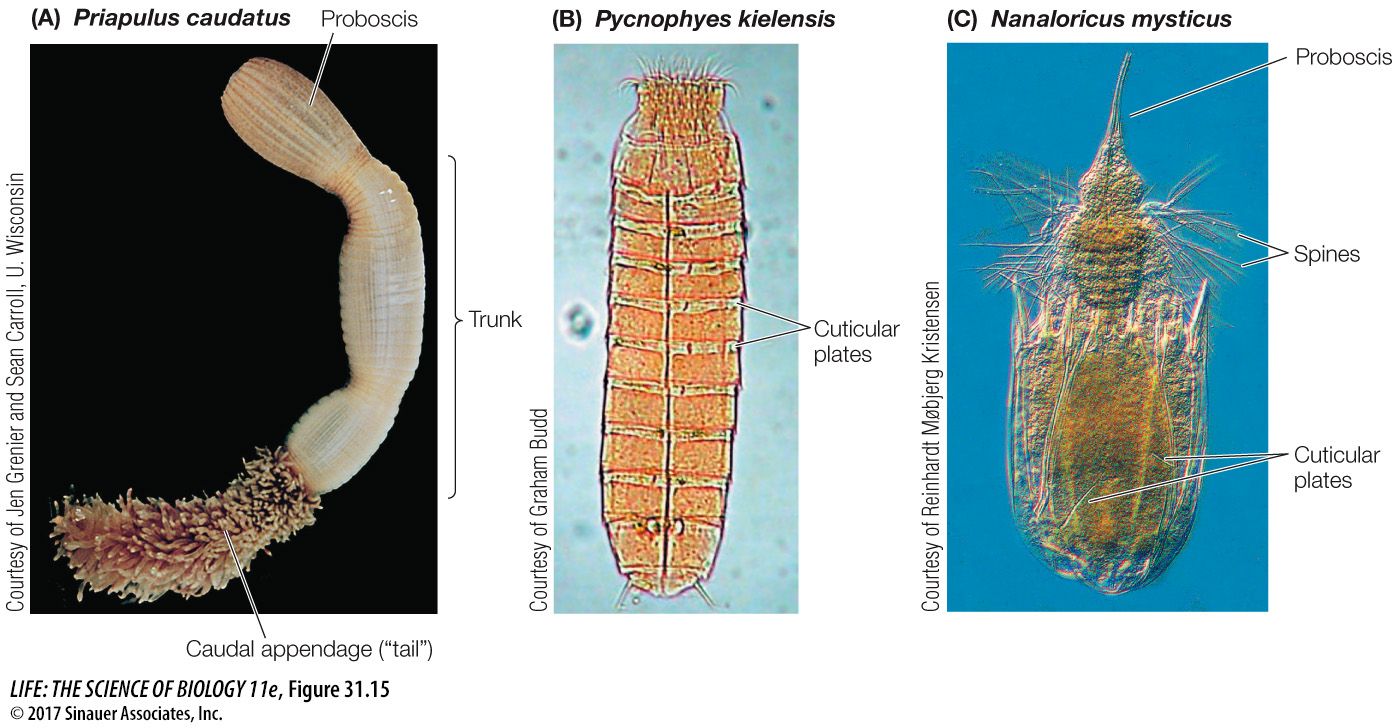

The 20 known species of priapulids are cylindrical, unsegmented, wormlike animals with a three-part body plan consisting of a proboscis, trunk, and caudal appendage (“tail”). It should be clear from their appearance why they were named after the Greek fertility god Priapus (Figure 31.15A). Priapulids range in length from 0.5 millimeters to 20 centimeters. They live in burrows in fine marine sediments and prey on soft-bodied invertebrates such as polychaetes, which they capture with a toothed, muscular pharynx that they evert through the mouth and then withdraw into the body together with the grasped prey. Fertilization is external, and most species have a larval form that also lives in the mud.

Figure 31.15 Wormlike Marine Ecdysozoans Members of three ecdysozoan groups are marine bottom-dwellers. (A) Most priapulid species live in burrows on the ocean floor, extending the proboscis to feed. (B) Kinorhynchs are virtually microscopic. The cuticular plates that cover their bodies are molted periodically. (C) Six cuticular plates form a “corset” around the minute loriciferan body.

About 180 species of kinorhynchs have been described. They live in marine sands and muds and are virtually microscopic; no kinorhynchs are longer than 1 millimeter. Their bodies are divided into 13 segments, each covered with a separate cuticular plate (Figure 31.15B). These plates are periodically molted during growth. Kinorhynchs feed by ingesting sediments through a retractable proboscis (the group name means “movable snout”). They then digest the organic material found in the sediment, which may include living algae as well as dead matter. Kinorhynchs have no distinct larval stage; fertilized eggs develop directly into juveniles, which emerge from their egg cases with 11 of the 13 body segments already formed.

Loriciferans are also minute animals less than 1 millimeter long. They were not discovered until 1983. About 100 living species are known to exist, although only about 30 of these have been formally described to date. The body is divided into a head, neck, thorax, and abdomen and is covered by six plates, from which the loriciferans get their name (Latin lorica, “corset”). The plates around the base of the neck bear anterior-directed spines of unknown function (Figure 31.15C). Loriciferans live in coarse marine sediments. Little is known about what they eat, but some species apparently eat bacteria.