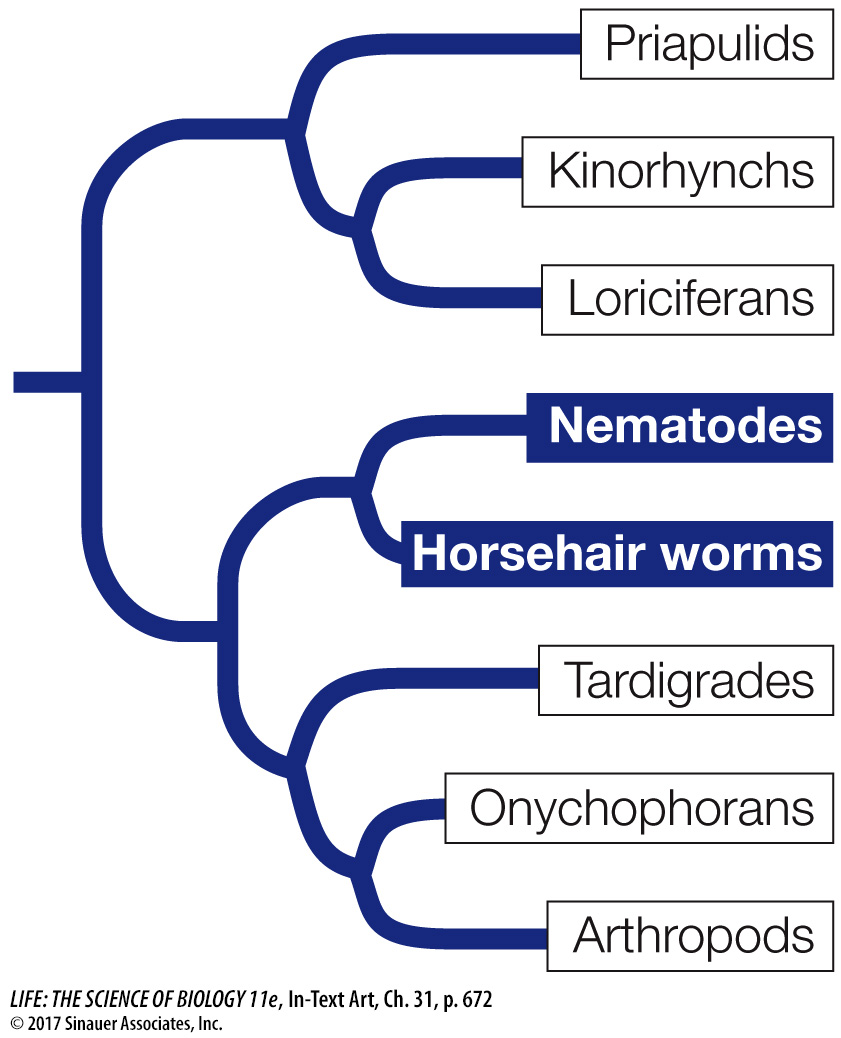

Nematodes and their relatives are abundant and diverse

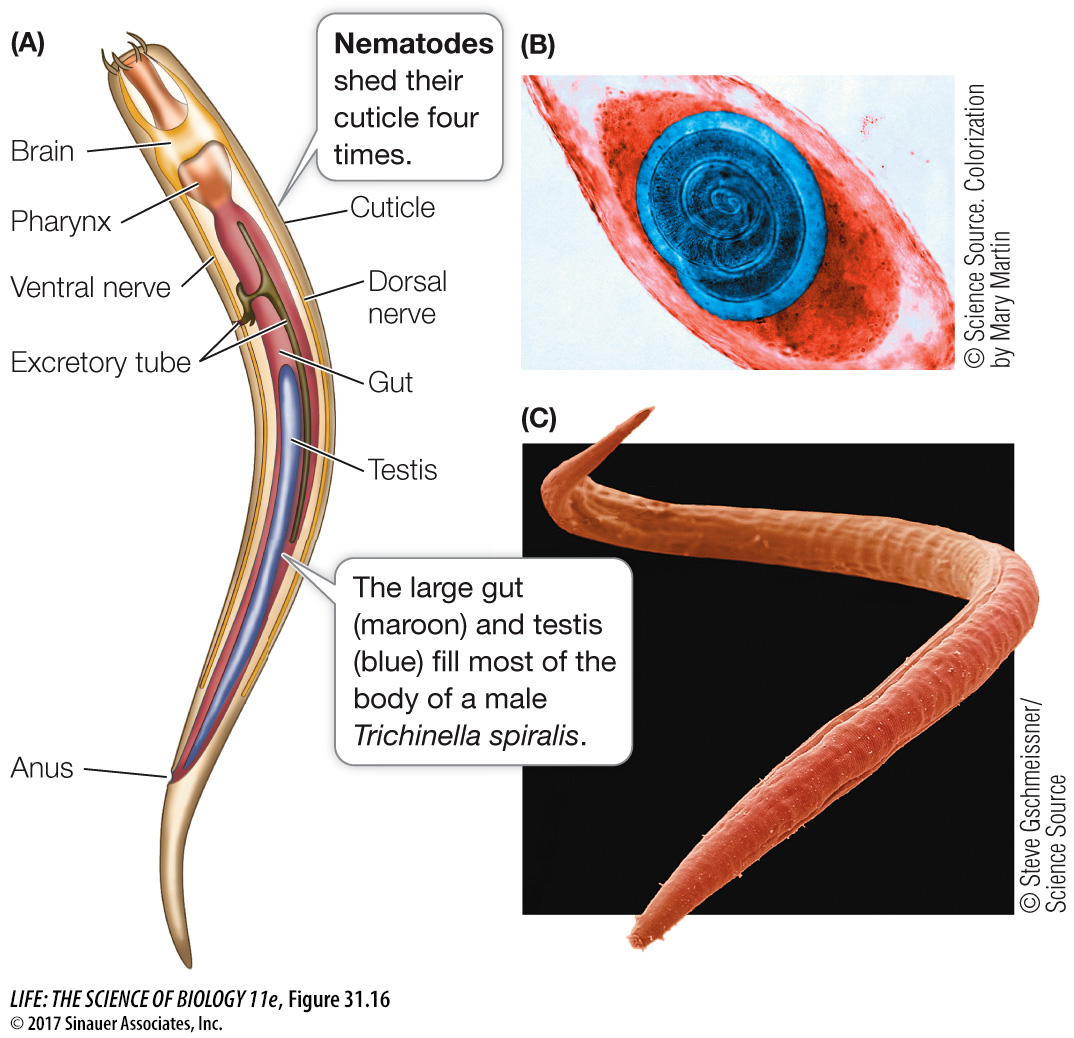

Nematodes (roundworms) have a thick, multilayered cuticle that gives their unsegmented body its shape (Figure 31.16). As a nematode grows, it sheds its cuticle four times. Nematodes exchange oxygen and nutrients with their environment through both the cuticle and the gut wall, which is only one cell layer thick. Materials are moved through the gut by rhythmic contraction of a highly muscular pharynx. Nematodes move by contracting their longitudinal muscles.

673

Nematodes are probably the most abundant and universally distributed of all animal groups. Many nematodes are microscopic; the largest known nematode, which reaches a length of 9 meters, is a parasite in the placentas of sperm whales. About 25,000 species have been described, but the actual number of living species may be more than 1 million. Countless nematodes live as scavengers in the upper layers of the soil, on the bottoms of lakes and streams, and in marine sediments. The topsoil of rich farmland may contain from 3 to 9 billion nematodes per acre. A single rotting apple may contain as many as 90,000 individuals.

One soil-

Many nematodes are predators, feeding on protists and small animals (including other roundworms). Most significant to humans, however, are the many species that parasitize plants and animals. The nematodes that parasitize humans (causing serious diseases such as trichinosis and elephantiasis), domestic animals, and economically important plants have been studied intensively in an effort to find ways of controlling them.

The structure of parasitic nematodes is similar to that of free-

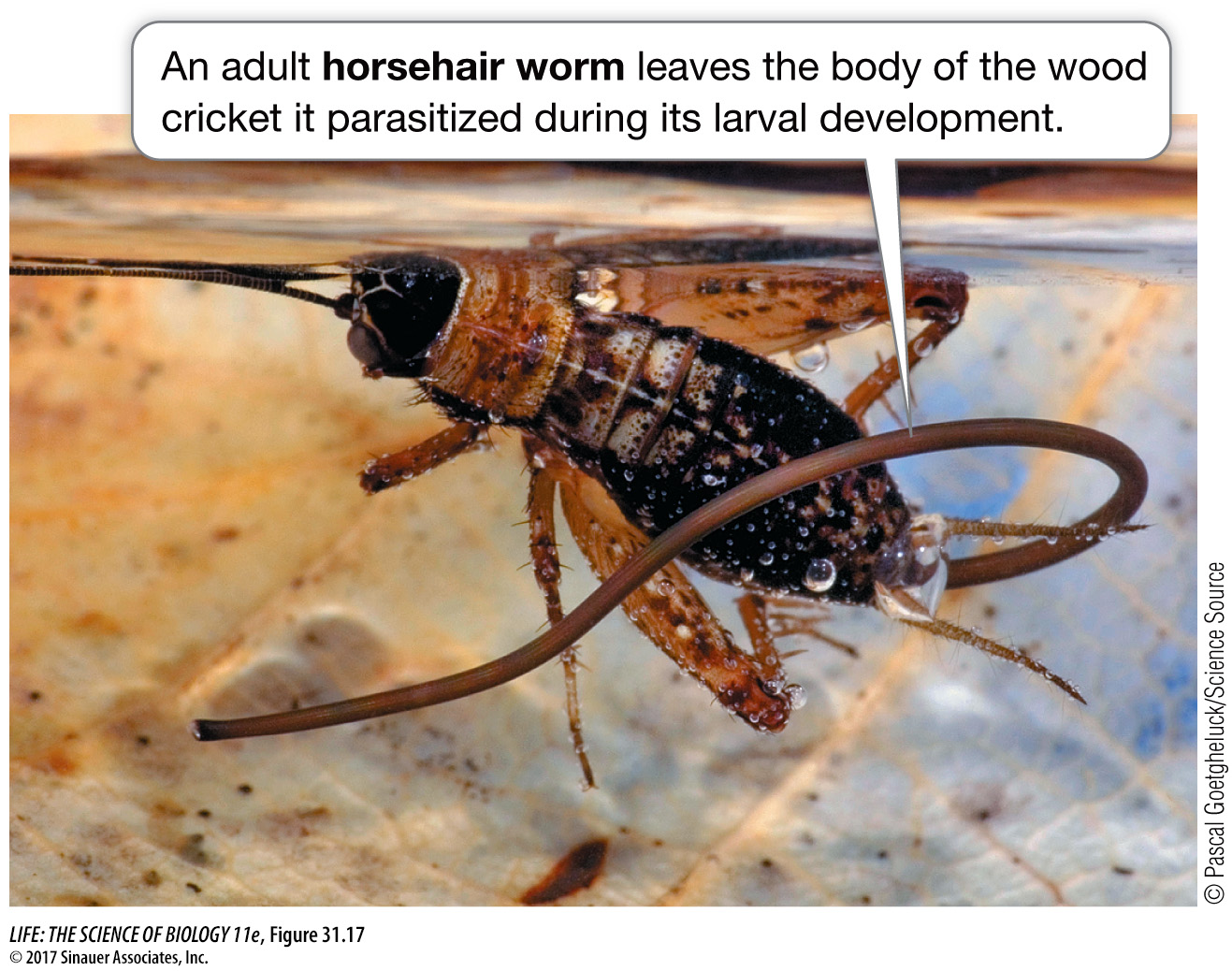

About 350 species of the unsegmented horsehair worms have been described. As their name implies, these animals are extremely thin in diameter; horsehair worms range from a few millimeters up to 1 meter in length. Most adult worms live in fresh water, among leaf litter and algal mats near the edges of streams and ponds. A few species live in damp soil.

Horsehair worm larvae are endoparasites of freshwater crayfishes and of terrestrial and aquatic insects (Figure 31.17). An adult horsehair worm has no mouth, and its gut is greatly reduced and probably nonfunctional. Some species may feed only as larvae, absorbing nutrients from their hosts across the body wall. But other species continue to shed their cuticles and grow after they have left their hosts, suggesting that adult worms may also absorb nutrients from their environment.