key concept

31.1

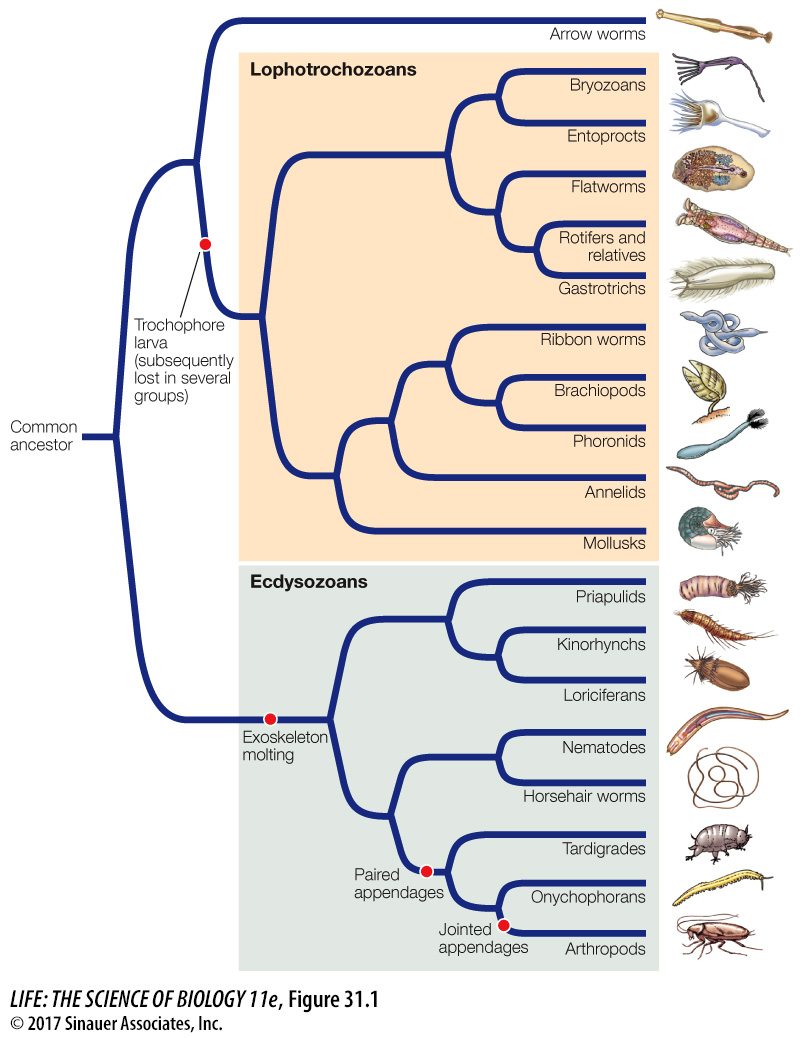

Protostomes Account for More Than Half of All Described Species

key concept

31.1

Protostomes Account for More Than Half of All Described Species

You may recall that the embryos of diploblastic animals (the ctenophores, placozoans, and cnidarians, which we discussed in Chapter 30) have two cell layers: an outer ectoderm and an inner endoderm (see Key Concept 30.1). Sometime after the origin of the diploblastic animals, a third embryonic cell layer evolved: the mesoderm, which lies between the ectoderm and the endoderm. Mesoderm is found in the two major triploblastic animal clades, the protostomes and the deuterostomes. If we were to judge solely on the basis of numbers, both of species and of individuals, the protostomes would emerge as by far the more successful of the two groups.

focus your learning

Ecdysozoans have an external covering—

a cuticle— that they must shed as they grow. Arthropods have a rigid exoskeleton and have made use of a great variety of appendages.

As noted in Key Concept 30.1, the name “protostome” means “mouth first.” In protostomes, the embryonic blastopore becomes the mouth as the animal develops. In contrast, in deuterostomes (“mouth second”), the blastopore becomes the anal opening of the gut. The protostomes are extremely varied, but they are all bilaterally symmetrical animals whose bodies exhibit two major derived traits:

An anterior brain that surrounds the entrance to the digestive tract

A ventral nervous system consisting of paired or fused longitudinal nerve cords

Other aspects of protostome body organization differ widely from group to group (Table 31.1). Before gene sequences were available for phylogenetic analysis, biologists considered the structure of the body cavity to be a critical feature in animal classification. But the results of genetic analyses have shown that body cavity forms have undergone considerable convergence in the course of protostome evolution. Although the common ancestor of the protostomes had a coelom, subsequent modifications of the coelom distinguish many protostome lineages. In some lineages (such as the flatworms and entoprocts), the coelom has been lost (that is, these groups reverted to an acoelomate state). Some lineages are characterized by a pseudocoel, a body cavity lined with mesoderm in which the internal organs are suspended (see Figure 30.6B). In two of the most prominent protostome clades, the coelom has been highly modified:

Arthropods lost the ancestral condition of the coelom over the course of evolution. Their internal body cavity has become a hemocoel, or “blood chamber,” in which fluid from an open circulatory system bathes the internal organs before returning to blood vessels.

Most mollusks have an open circulatory system with some of the attributes of the hemocoel, but they retain vestiges of an enclosed coelom around their major organs.

| Group | Body cavity | Digestive tract | Circulatory system |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arrow worms | Coelom | Complete | None |

| Lophotrochozoans | |||

| Bryozoans | Coelom | Complete | None |

| Entoprocts | None | Complete | None |

| Flatworms | None | Blind gut | None |

| Rotifers | Pseudocoel | Complete | None |

| Gastrotrichs | Pseudocoel | Complete | None |

| Ribbon worms | Coelom | Complete | Closed |

| Brachiopods | Coelom | Complete in most | Open |

| Phoronids | Coelom | Complete | Closed |

| Annelids | Coelom | Complete | Closed or open |

| Mollusks | Reduced coelom | Complete | Open except in cephalopods |

| Ecdysozoans | |||

| Nematodes | Pseudocoel | Complete | None |

| Horsehair worms | Pseudocoel | Greatly reduced | None |

| Arthropods | Hemocoel | Complete | Open |

The protostomes can be divided into two major clades—

Activity 31.1 Features of the Protostomes

Activity 31.2 Protostome Classification