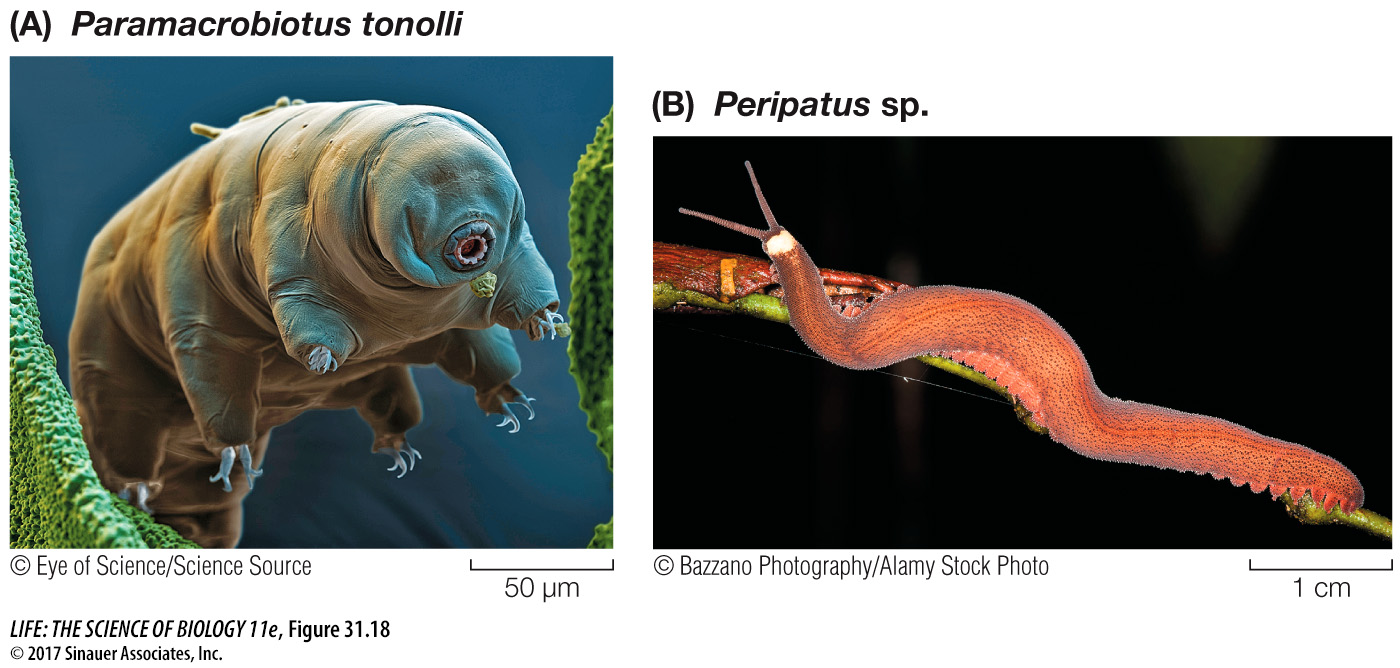

The two living groups most closely related to the arthropods provide us with clues about the likely appearance of ancestral arthropod appendages. Tardigrades (water bears) have fleshy, unjointed legs and use their fluid-filled body cavities as hydrostatic skeletons (Figure 31.18A). Tardigrades are tiny (0.5–1.5 mm long) and lack both a circulatory system and gas exchange organs. The 1,200 known extant species live in marine sands and on temporary water films on plants. When these films dry out, the animals also lose water and shrink to small, barrel-shaped objects that can survive for at least a decade in a dormant state. Tardigrades have been found at densities as high as 2 million per square meter of moss.

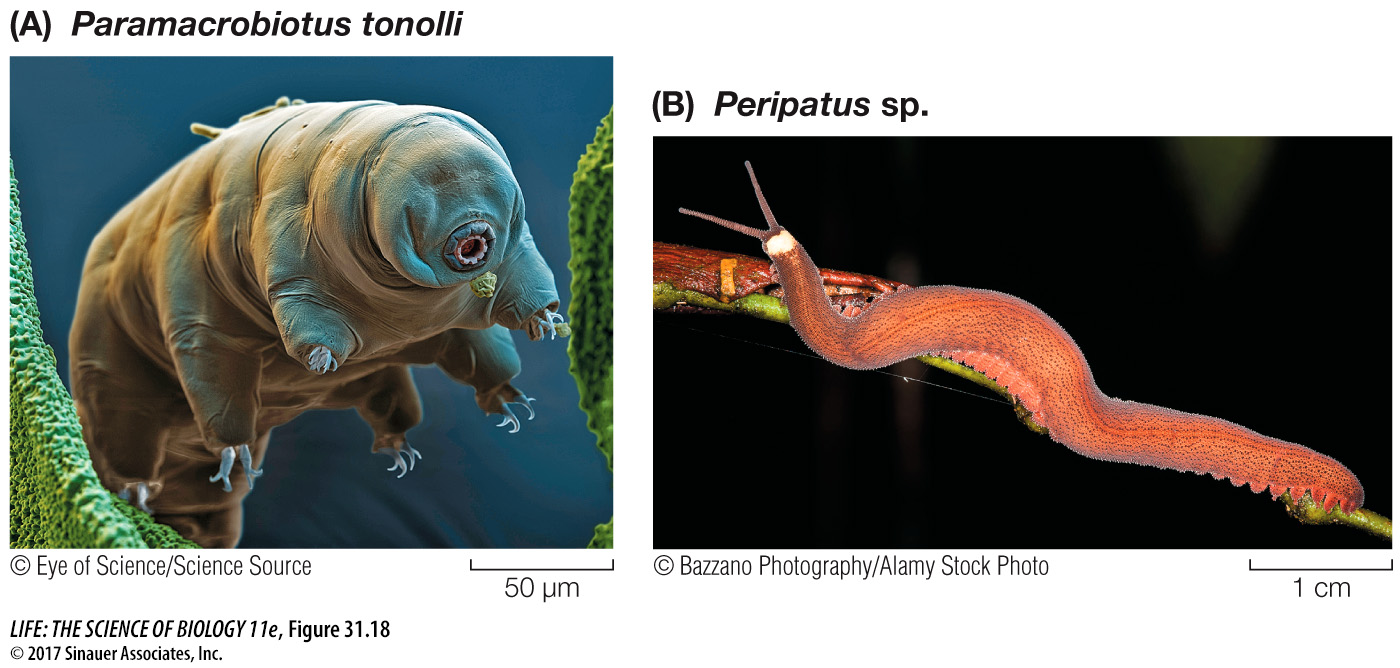

Figure 31.18 Arthropod Relatives with Unjointed Appendages (A) Tardigrades (water bears) can be abundant on the wet surfaces of mosses and plants and in temporary pools of water. (B) Onychophorans (velvet worms) have unjointed legs and use the body cavity as a hydrostatic skeleton. They are sometimes referred to as “living fossils,” meaning they are an ancient group that has changed very little over millennia.

Until fairly recently, biologists debated whether the onychophorans (velvet worms) were more closely related to annelids or to arthropods, but molecular evidence clearly links them to the latter. Indeed, with their soft, fleshy, unjointed, claw-bearing legs and elongate bodies, onychophorans may be similar in appearance to the ancestors of arthropods (Figure 31.18B). The 180 known species of onychophorans live in leaf litter in humid tropical environments. They have soft, segmented bodies that are covered by a thin, flexible cuticle that contains chitin. Like the tardigrades, they use their fluid-filled body cavities as hydrostatic skeletons. Fertilization is internal, and the large, yolky eggs are brooded within the body of the female.