Flatworms, rotifers, and gastrotrichs are structurally diverse relatives

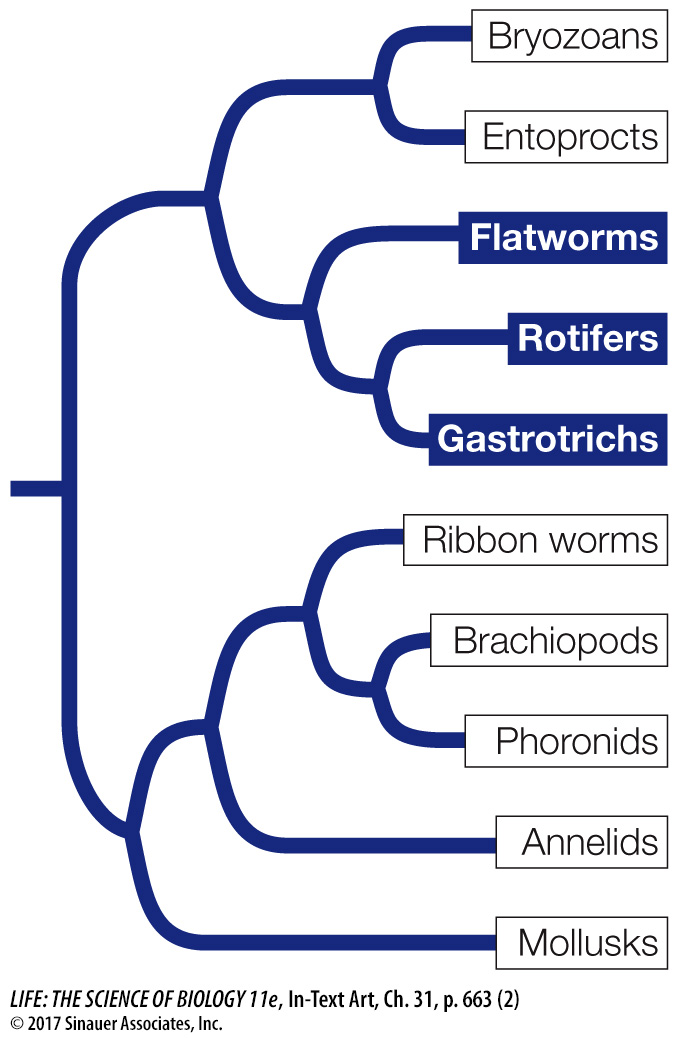

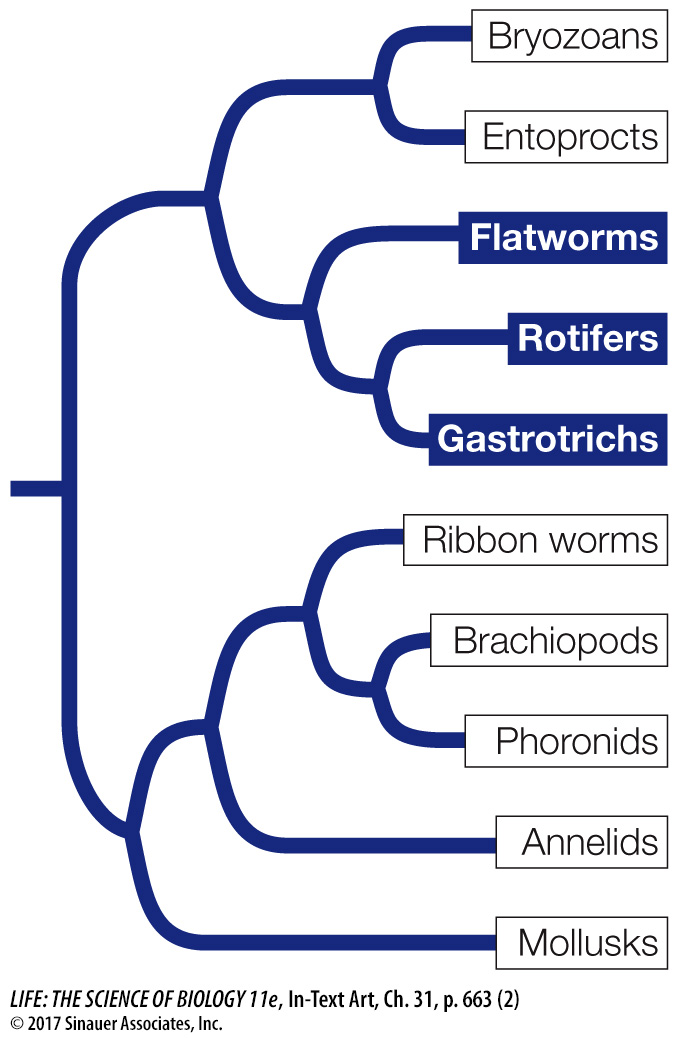

Flatworms, rotifers, gastrotrichs, and their close relatives are a structurally diverse group of organisms whose relationships to one another have been hypothesized only recently. Recent genomic studies show that this monophyletic lophotrochozoan group includes both acoelomate subgroups (e.g., the flatworms) and pseudocoelomate subgroups (e.g., the rotifers and gastrotrichs), and yet the closest relatives of this group—the bryozoans and entoprocts—are coelomate and acoelomate, respectively. Thus this group provides an example of the evolutionary convergence in body cavity form that we described in Key Concept 31.1.

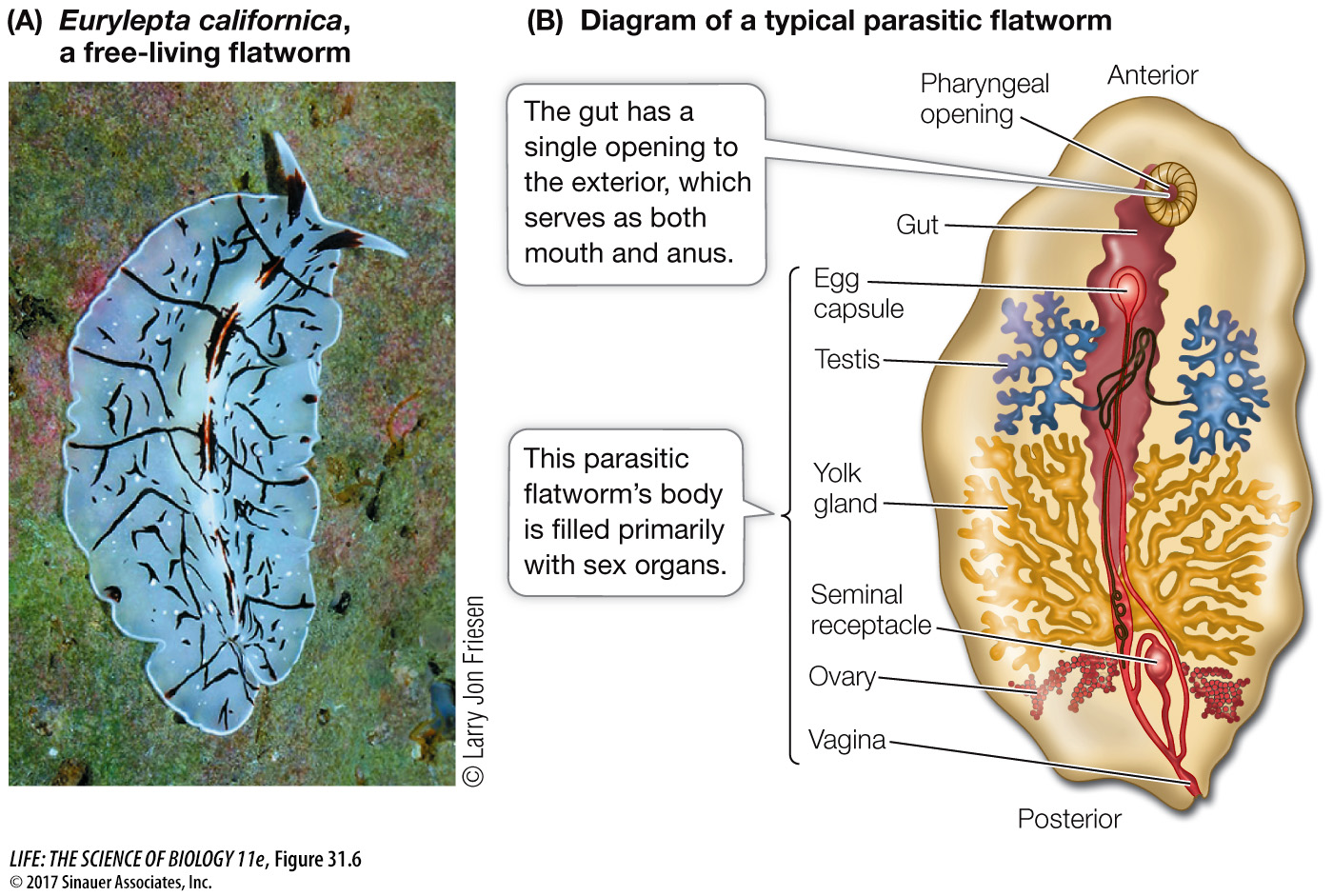

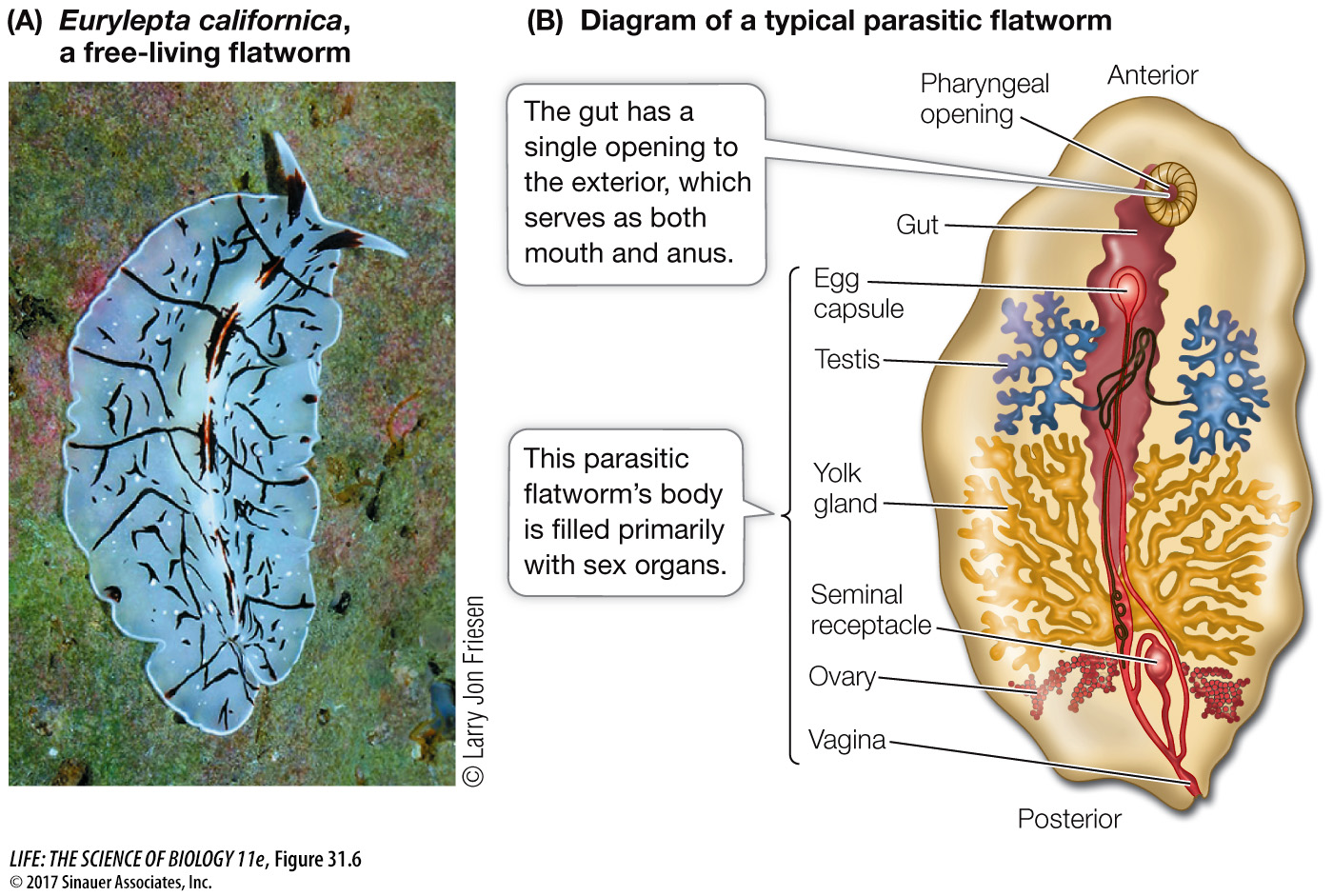

FLATWORMS Flatworms lack specialized organs for transporting oxygen to their internal tissues. In the absence of a gas transport system, each cell must be near a body surface, a requirement met by the dorsoventrally flattened body form that gives these animals their common name. The digestive tract of a free-living flatworm consists of a mouth opening into a blind gut. The gut is often highly branched, forming intricate patterns that increase the surface area available for the absorption of nutrients. Some small free-living flatworms are cephalized, with a head bearing chemoreceptor organs, two simple eyes, and a tiny brain composed of anterior thickenings of the longitudinal nerve cords. Free-living flatworms glide over surfaces on a layer of mucus, powered by broad bands of cilia (Figure 31.6A).

Figure 31.6 Flatworms Include Both Parasites and Free-Living Forms (A) Some flatworm species, such as this Pacific marine flatworm, are free-living. (B) The fluke diagrammed here lives endoparasitically in the gut of sea urchins and is typical of endoparasitic flatworms. Because their hosts provide all the nutrition they need, these internal parasites do not require elaborate feeding or digestive organs and can devote most of their bodies to reproduction.

Although many flatworms are free-living, most flatworm species are parasites. Of the parasitic species, most are endoparasites. There are also flatworms that feed externally on animal tissues (living or dead), and some graze on plants. A likely evolutionary transition was from feeding on dead organisms to feeding on the body surfaces of dying hosts to invading and consuming parts of healthy hosts.

Most of the 30,000 known species of living flatworms are tapeworms and flukes; members of these two groups are endoparasites, particularly of vertebrates (Figure 31.6B). Because they absorb digested food from the digestive tracts of their hosts, many endoparasitic flatworms lack digestive tracts of their own. Some cause serious human diseases, such as schistosomiasis, which is common in parts of Asia, Africa, and South America. The species that causes this devastating disease has a complex life cycle involving both freshwater snails and mammals as hosts. Members of another flatworm group, the monogeneans, are ectoparasites of fishes and other aquatic vertebrates. The turbellarians include most of the free-living species.

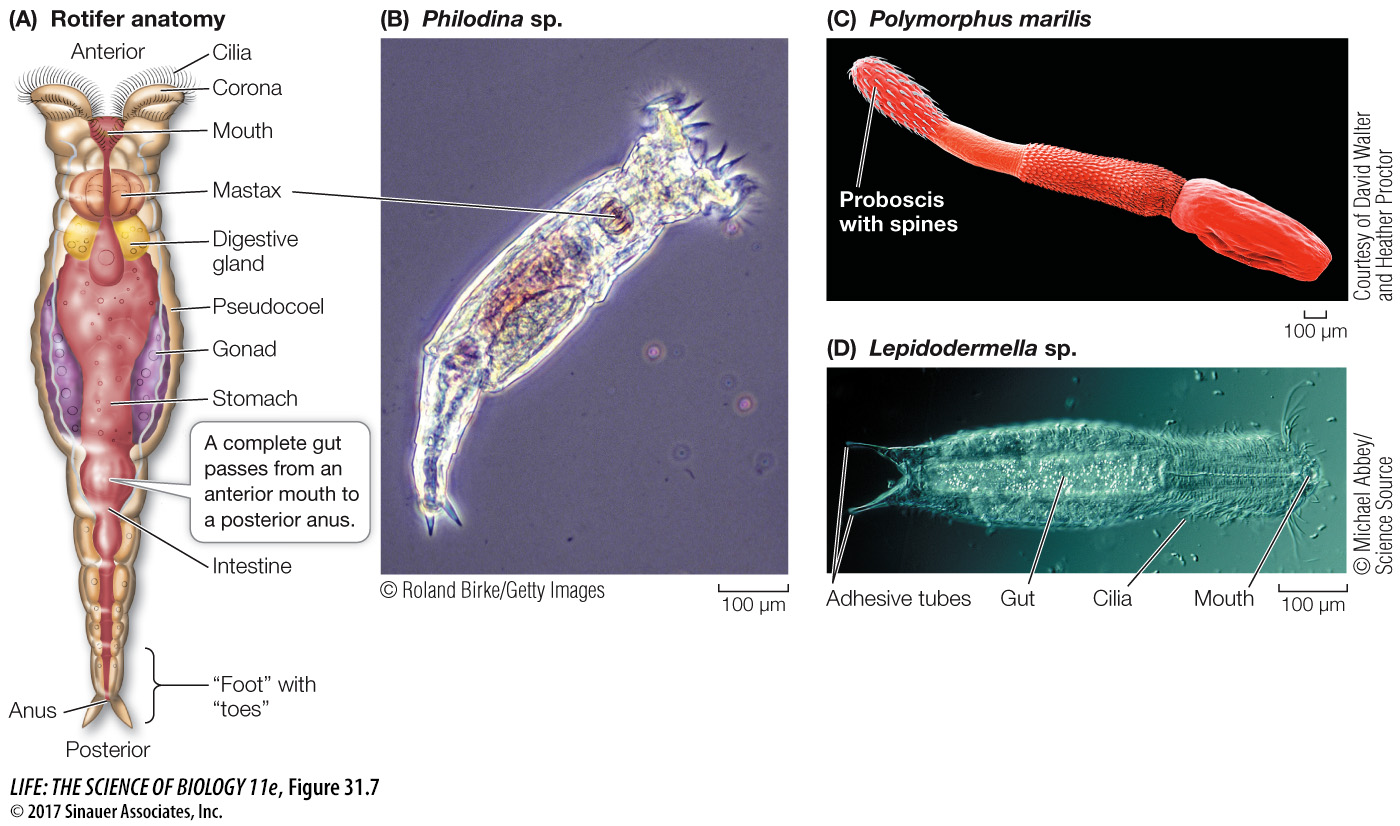

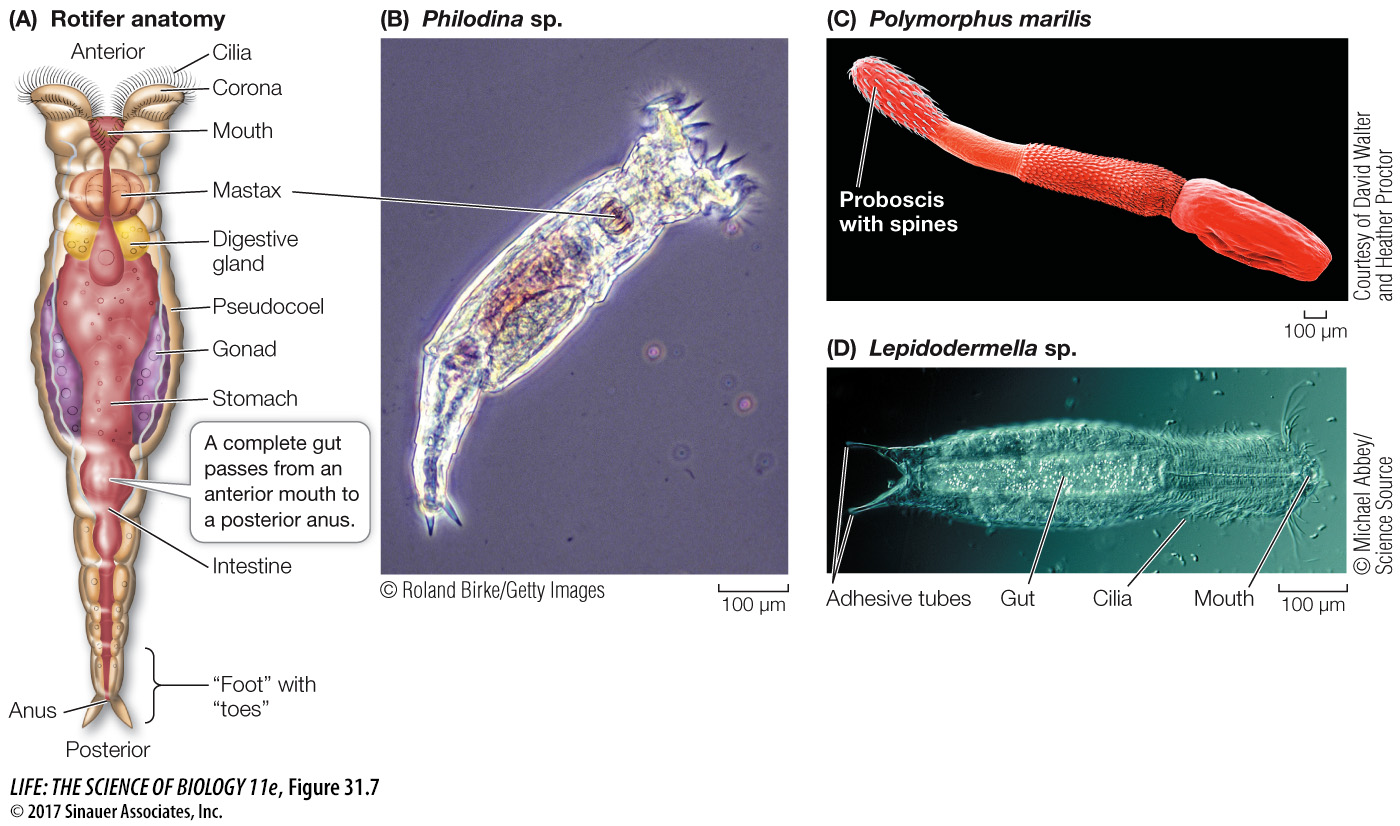

ROTIFERS Most species of rotifers are tiny (50–500 µm long)—smaller than some ciliate protists—but they have specialized internal organs (Figure 31.7A and B). A complete gut passes from an anterior mouth to a posterior anus; the body cavity is a pseudocoel that functions as a hydrostatic skeleton. Rotifers typically propel themselves through the water by means of rapidly beating cilia rather than by muscular contraction.

Figure 31.7 Rotifers and Gastrotrichs (A) The rotifer diagrammed here reflects the general structure of many rotifers. (B) A micrograph reveals the internal complexity of the microscopic rotifers. (C) Spiny-headed worms are parasitic rotifer relatives. The spines of the proboscis anchor the animal to the organs of its host. (D) Gastrotrichs superficially resemble rotifers but have flattened ventral surfaces covered with cilia, as flatworms do.

Media Clip 31.3 Rotifer Feeding

The most distinctive organ of rotifers is a conspicuous ciliated organ called the corona, which surmounts the head of many species. Coordinated beating of the cilia sweeps particles of organic matter from the water into the animal’s mouth and down to a complicated structure called the mastax, in which food is ground into small pieces. By contracting muscles around the pseudocoel, a few rotifer species that prey on protists and small animals can protrude the mastax through the mouth and seize small objects with it.

Most of the known species of rotifers live in fresh water. Some species rest on the surfaces of mosses or lichens in a desiccated, inactive state until it rains. When rain falls, they absorb water and become mobile, feeding in the films of water that temporarily cover the plants. Most rotifers live no longer than a few weeks.

Both males and females are found in some species of rotifers, but only females are known among the bdelloid rotifers (the b in “bdelloid” is silent). Biologists have concluded that the bdelloid rotifers may have existed for tens of millions of years without regular sexual reproduction. Lack of genetic recombination generally leads to the buildup of deleterious mutations, so long-term *asexual reproduction typically leads to extinction. Recent studies, however, have indicated that bdelloid rotifers may avoid this problem by picking up fragments of genes from their environment during the desiccation–rehydration cycle, which allows genetic recombination among individuals in the absence of direct sexual exchange.

*connect the concepts The consequences of asexual reproduction, and the reasons that it commonly leads to a buildup of deleterious mutations, are discussed in Key Concept 20.5.

A few highly reduced lineages appear to have descended from the free-living rotifers. The spiny-headed worms are parasites with complex life cycles, often parasitizing several animal hosts (Figure 31.7C). The jaw worms are tiny marine organisms that glide between sand grains in shallow marine environments. Although spiny-headed worms and jaw worms are structurally quite distinct, molecular analyses have revealed that both groups are essentially highly modified rotifers.

GASTROTRICHS The 800 known species of gastrotrichs (also called “hairy backs”) are abundant, tiny (0.05–3 mm) animals that live in marine sediments, in fresh waters, and in the water films that surround grains of soil. Their transparent bodies have a flat ventral surface that is covered with cilia (Figure 31.7D). Most species are simultaneous hermaphrodites, with both male and female reproductive organs, although the male organs have been greatly reduced or lost in some species that reproduce asexually.