Fins and swim bladders improved stability and control over locomotion

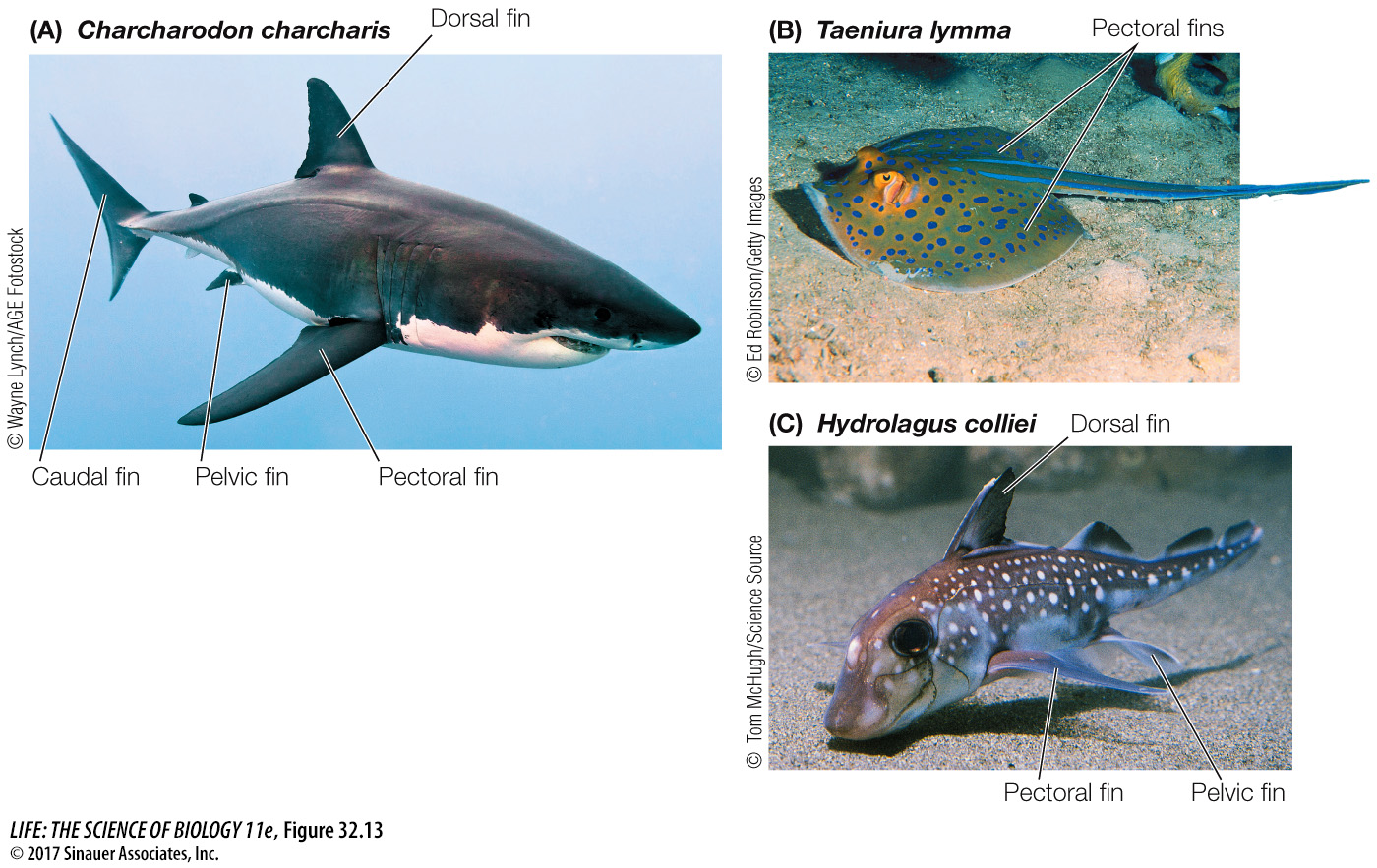

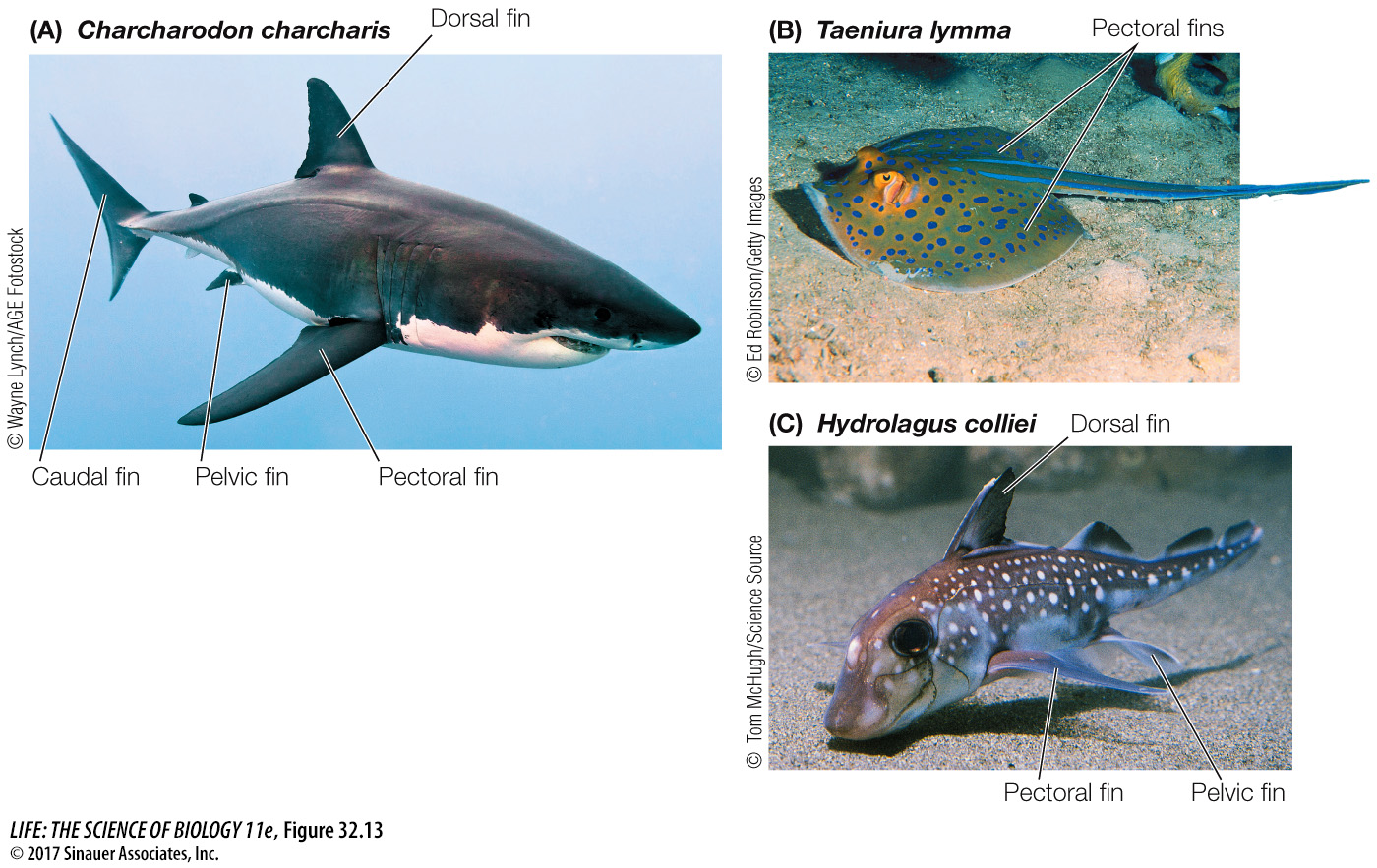

Most jawed fishes have a pair of pectoral fins just behind the gill slits and a pair of pelvic fins anterior to the anus (see Figures 32.9 and 32.13A). These paired fins stabilize the fish’s position in water (and in some cases, help propel it). Median dorsal and anal fins also stabilize the fish, or may be used for propulsion in some species. In many fishes, the caudal (tail) fin helps propel the animal and enables it to turn rapidly.

Several groups of jawed fishes became abundant during the Devonian. Among them were the chondrichthyans—sharks, skates, and rays (about 1,000 living species) and chimaeras (40 living species). Like hagfishes and lampreys, these fishes have a skeleton composed entirely of cartilage. Their skin is flexible and leathery, sometimes bearing scales that give it the consistency of sandpaper. Sharks move forward by means of lateral (side-to-side) undulations of the body and caudal fin (Figure 32.13A). Skates and rays propel themselves by means of vertical undulating movements of their greatly enlarged pectoral fins (Figure 32.13B).

Figure 32.13 Chondrichthyans (A) Most sharks are active marine predators, as epitomized by the great white shark seen here. (B) Skates and rays, represented here by a blue spotted fantail ray, feed on the ocean bottom. Their modified pectoral fins are used for propulsion; their other fins are greatly reduced. (C) A chimaera, or ratfish. Many of these deep-sea fishes possess modified dorsal fins that contain toxins.

Most sharks are predators, but some feed by straining plankton from the water. Most skates and rays live on the ocean floor, where they feed on mollusks and other animals buried in the sediments. Nearly all chondrichthyans live in the oceans, but a few are estuarine or migrate into lakes and rivers. One group of stingrays is found in river systems of South America. The less familiar chimaeras (Figure 32.13C) live in deep-sea or cold waters.

One lineage of aquatic gnathostomes gave rise to the bony vertebrates, which soon split into two main lineages—the ray-finned fishes and the lobe-limbed vertebrates. Bony vertebrates have internal skeletons of calcified, rigid bone rather than flexible cartilage. In early bony vertebrates, gas-filled sacs supplemented the gas exchange function of the gills by giving the animals access to atmospheric oxygen. These features enabled these fishes to live where oxygen was periodically in short supply, as it often is in freshwater environments. In the ray-finned fishes, these lunglike sacs evolved into swim bladders, which are organs of buoyancy. By adjusting the amount of gas in its swim bladder, ray-finned fishes can control the depth at which it remains suspended in the water while expending very little energy to maintain its position.

The outer body surface of most species of ray-finned fishes is covered with thin, flat, lightweight scales that provide protection or enhance movement through the water. The gills open into a single chamber covered by a hard flap, called an operculum. Movement of the operculum increases the flow of water over the gills, where gas exchange takes place.

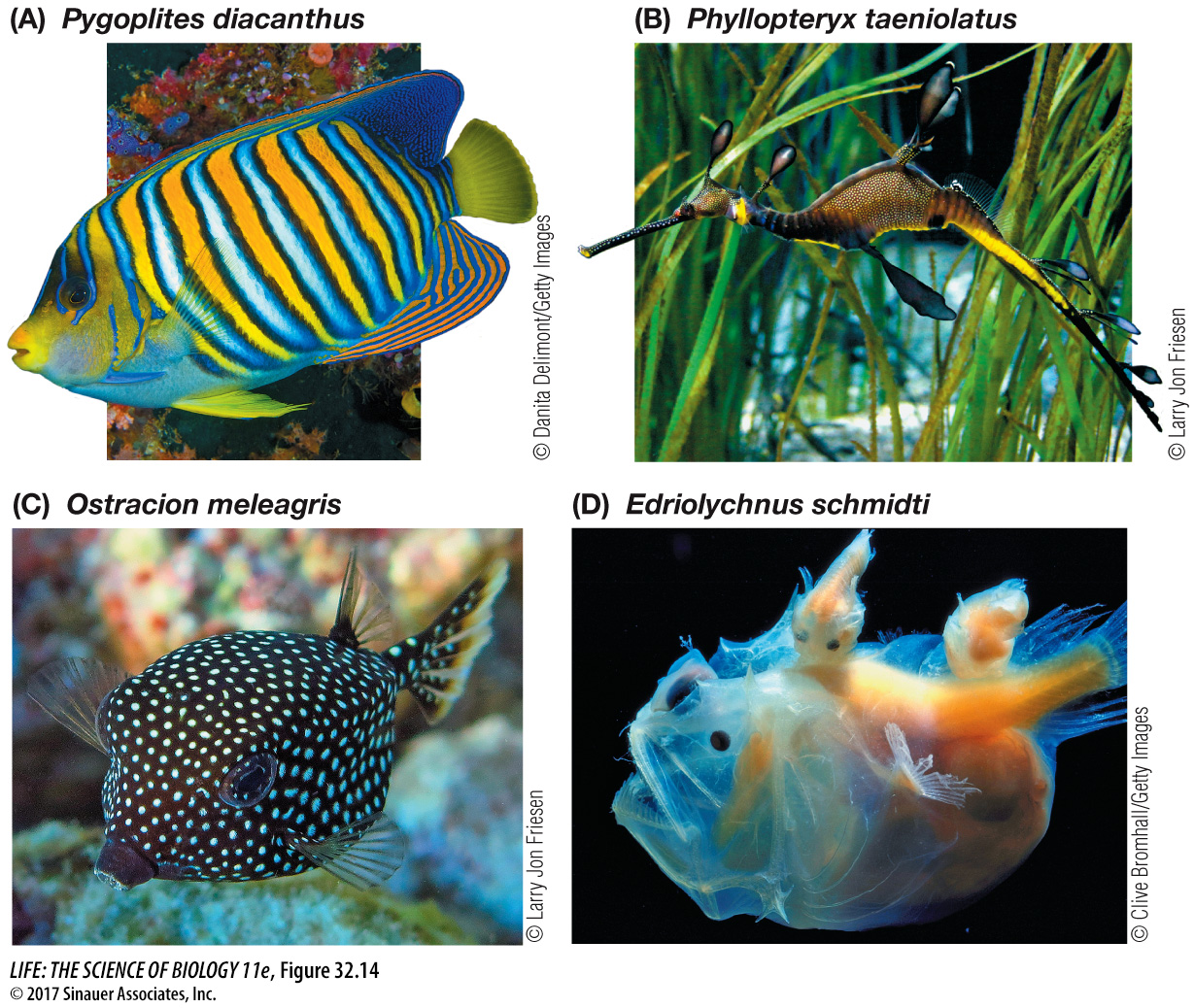

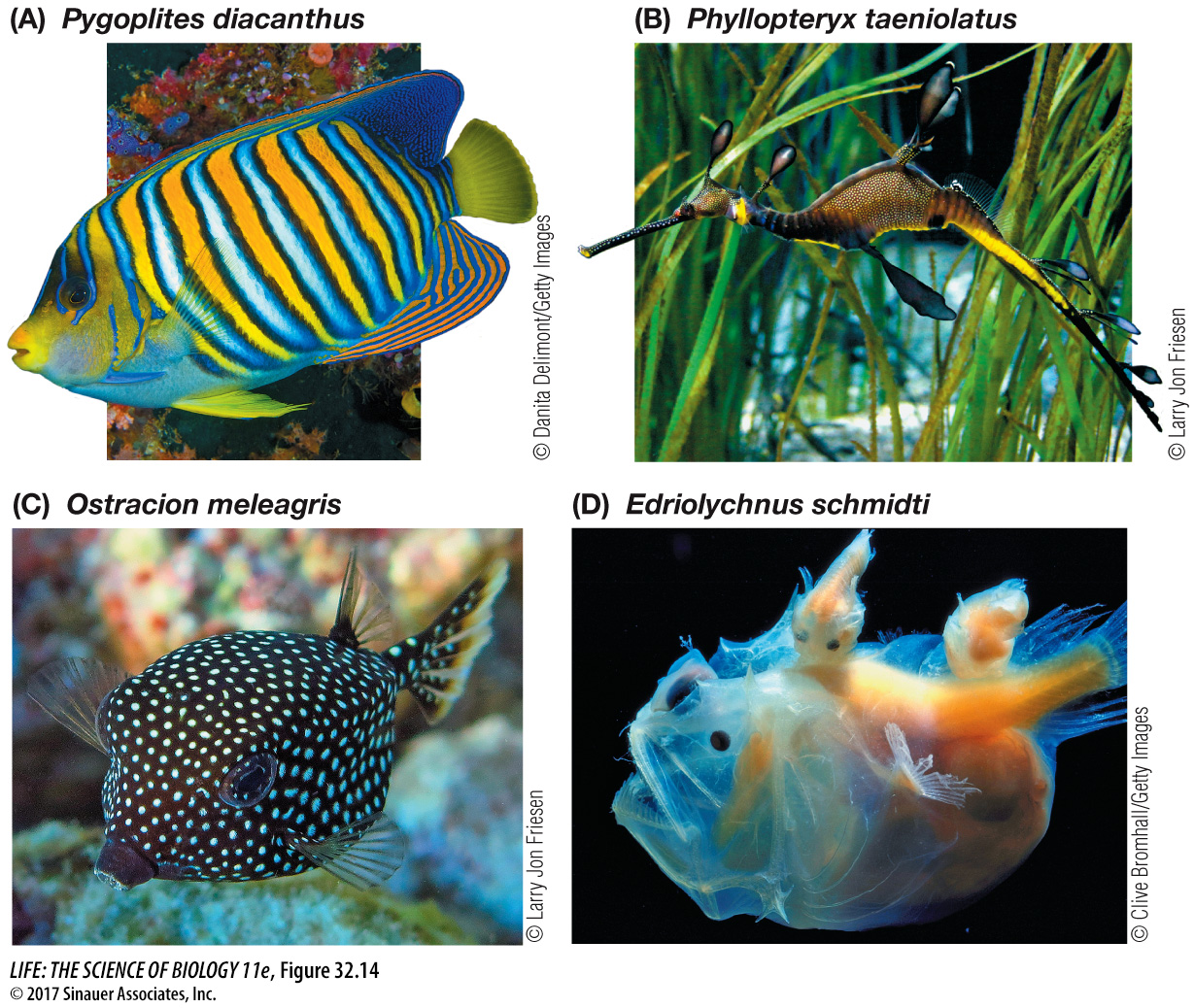

Ray-finned fishes began to diversify during the Mesozoic era and continued to radiate extensively throughout the Tertiary period. Today there are about 32,000 known living species, encompassing a remarkable variety of sizes, shapes, and lifestyles (Figure 32.14). The smallest are less than 1 centimeter long; the largest weigh as much as 900 kilograms. Ray-finned fishes exploit nearly all types of aquatic food sources. In the oceans they filter plankton from the water, rasp algae from rocks, eat corals and other soft-bodied colonial animals, dig animals from soft sediments, and prey on virtually all kinds of other fishes. In fresh water they eat plankton, devour insects, eat fruits that fall into the water, and prey on other aquatic vertebrates and, occasionally, terrestrial vertebrates. Many ray-finned fishes are solitary, but in open water others form large aggregations called schools. Many species perform complicated behaviors to maintain schools, build nests, court mates, and care for their young.

Figure 32.14 Diversity among the Ray-Finned Fishes (A) The brightly colored regal angelfish lives around Indo-Pacific coral reefs. Its deep, laterally compressed body and enlarged dorsal and anal fins increase its apparent size. (B) This slow-moving weedy seadragon relies on its highly modified body and fins to provide camouflage in swaying seaweed. (C) This spotted boxfish is a member of another large ray-fin clade, the serranids, which also includes the sea basses and groupers. (D) Deep-sea anglerfishes live below the level of light penetration. The large fish shown here is a female; the two smaller fishes are males, which fuse to the female for life.

Although ray-finned fishes can readily control their position in open water using their fins and swim bladder, their eggs tend to sink. Some species produce small eggs that are buoyant enough to complete their development in open water, but many marine fishes move to food-rich shallow waters to lay their eggs. That is why coastal waters and estuaries are so important in the life cycles of many marine fishes. Some ray-finned fishes, such as salmon, are anadromous, moving from the ocean to the fresh waters in which they breed.