Jointed limbs enhanced support and locomotion on land

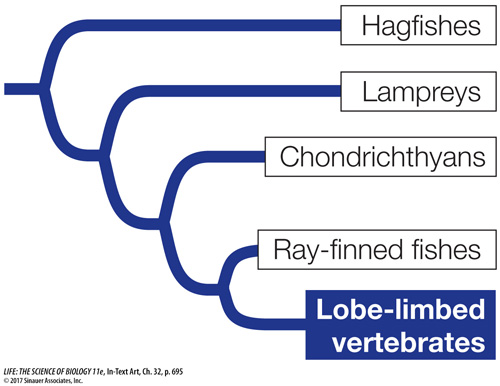

In the lobe-limbed vertebrates, the paired pelvic and pectoral fins developed into more muscular fins that were joined to the body by a single enlarged bone. The modern representatives of these lobe-limbed vertebrates include the coelacanths, lungfishes, and tetrapods.

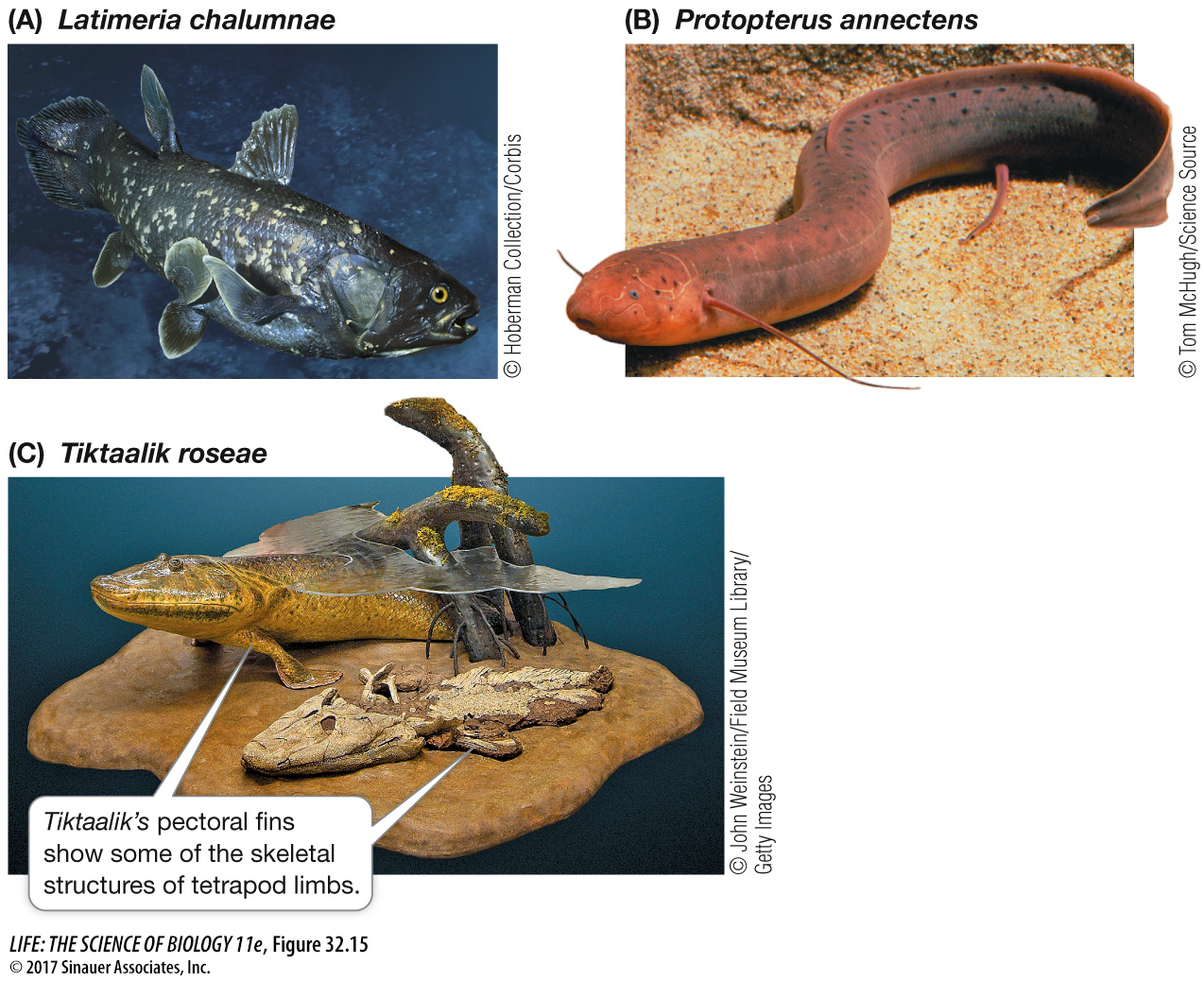

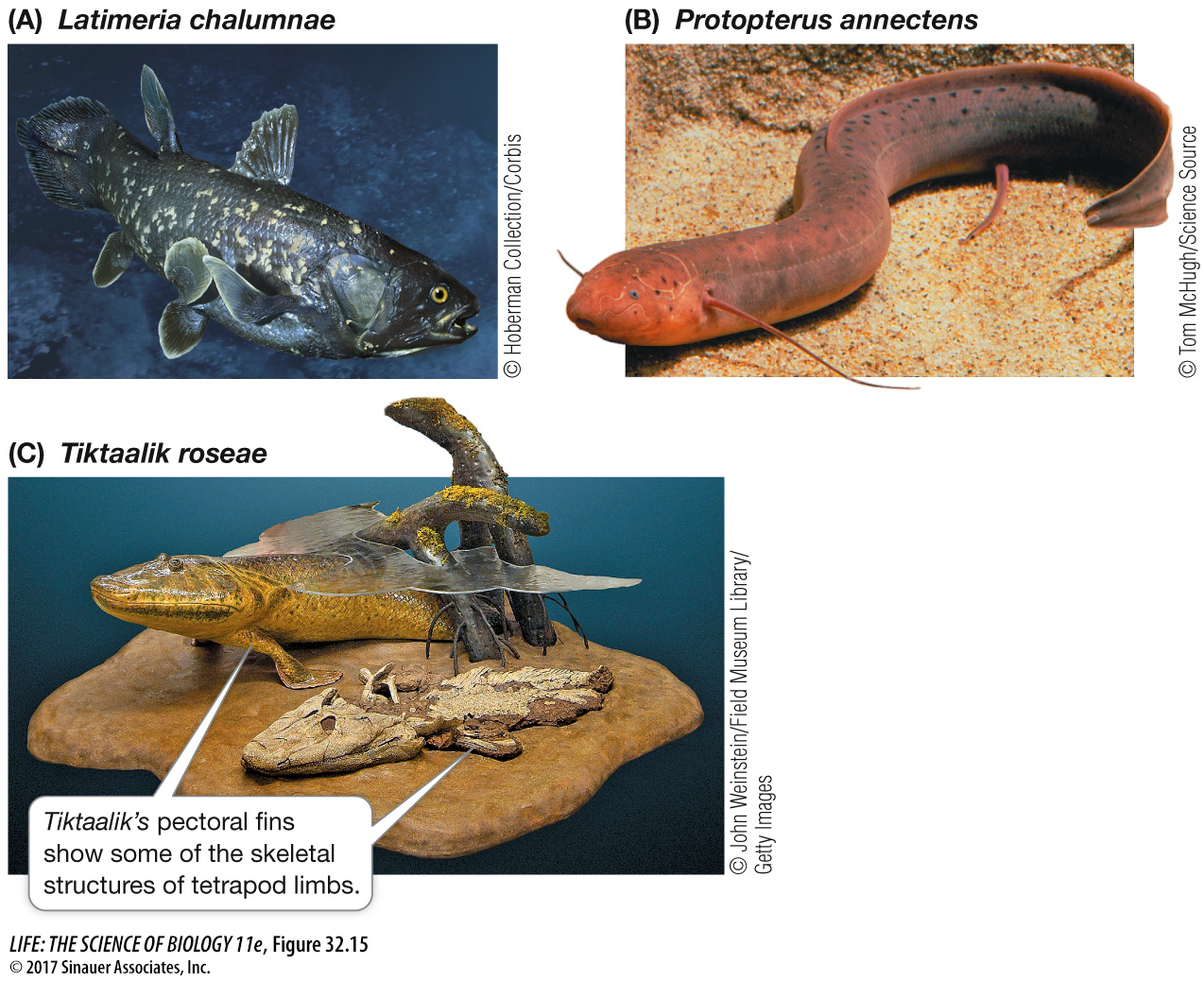

The coelacanths flourished from the Devonian until about 65 million years ago, when they were thought to have become extinct. But in 1938 a commercial fisherman caught a living coelacanth off South Africa. Since that time, hundreds of individuals of this extraordinary fish, Latimeria chalumnae, have been collected (Figure 32.15A). A second species, L. menadoensis, was discovered in 1998 off the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. Latimeria, a predator of other fishes, reaches a length of about 1.8 meters and weighs up to 82 kilograms. Its skeleton is composed mostly of cartilage, not bone. The cartilaginous skeleton is a derived feature in this clade because it had bony ancestors.

Figure 32.15 The Closest Relatives of Tetrapods (A) The African coelacanth, discovered in deep waters of the Indian Ocean off the South African coast, represents one of two surviving species of a group that was once thought to be extinct. (B) All surviving lungfish species, such as this African lungfish, live in the Southern Hemisphere. (C) Tiktaalik, a fossil lobe-limbed vertebrate from the Devonian, is believed to represent a transitional species intermediate between the finned fishes and the limbed tetrapods.

Media Clip 32.3 Coelacanths in the Deep Seas

Lungfishes were important predators in shallow-water habitats in the Devonian, but most lineages died out. The six surviving species live in stagnant swamps and muddy waters in South America, Africa, and Australia (Figure 32.15B). Lungfishes have lungs derived from the lunglike sacs of their ancestors as well as gills. When ponds dry up, individuals of most species can burrow deep into the mud and survive for many months in an inactive state while breathing air.

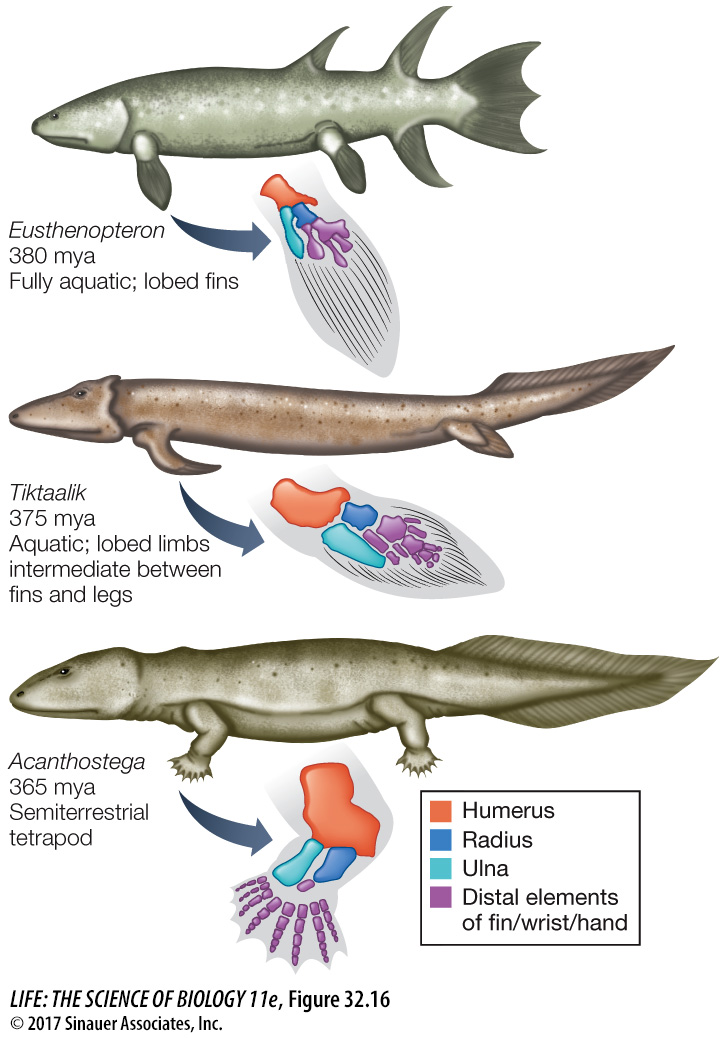

It is believed that some early aquatic lobe-limbed vertebrates began to use terrestrial food sources, became more fully adapted to life on land, and eventually evolved to become ancestral tetrapods (“four legs”). How was this transition from an animal that swam in water to one that walked on land accomplished? Early in 2006, scientists reported the discovery of a Devonian fossil lobe-limbed vertebrate, since then named Tiktaalik, which possessed intermediate appendages between the fins of fishes and the limbs of terrestrial tetrapods (Figure 32.15C). It appears that limbs capable of propping up a large fish and making the front-to-rear movements necessary for walking evolved while these animals still lived in water. These limbs appear to have functioned in holding the animals upright in shallow water, perhaps even allowing them to hold their head above the water’s surface. These same structures were then co-opted for movement on land, at first probably for foraging on brief trips out of water.

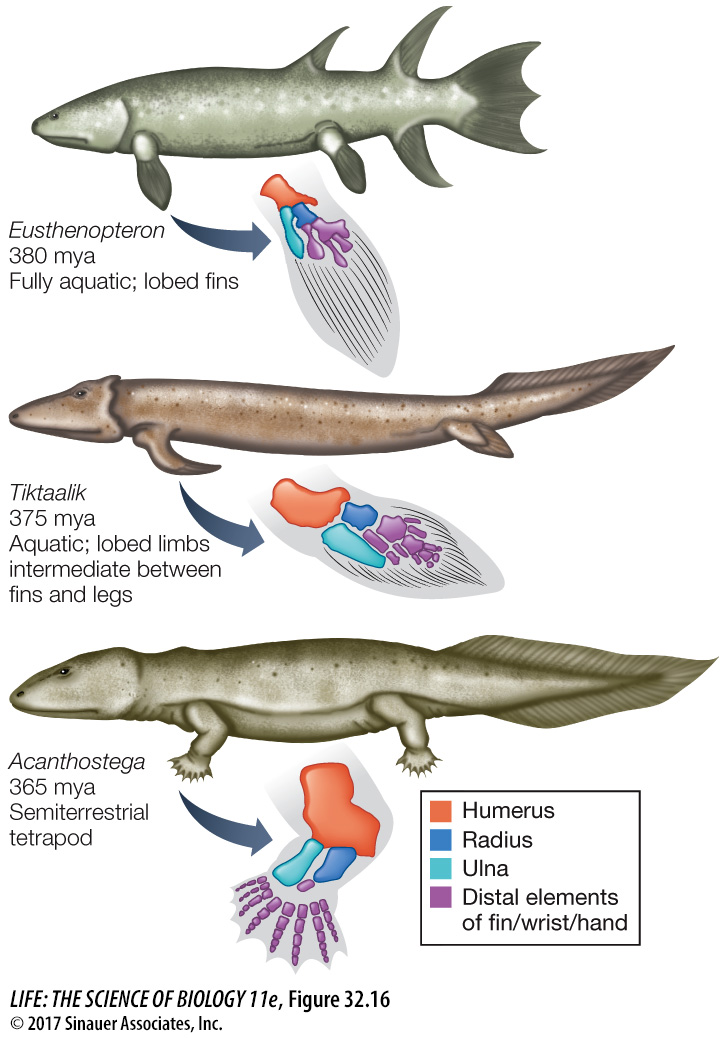

Among the lobe-limbed vertebrates, limbs capable of movement on land evolved from the short, muscular fins of aquatic ancestors (Figure 32.16). The resulting four terrestrial limbs give the tetrapods their name. The basic skeletal elements of those limbs can be traced through major changes in limb form and function among the terrestrial vertebrates.

Figure 32.16 Tetrapod Limbs Are Modified Fins The major skeletal elements of the tetrapod limb were already present in aquatic lobe-limbed fishes some 380 million years ago. The relative sizes and positions of these elements changed as lobe-limbed vertebrates moved to a terrestrial environment, where limbs were needed to support and move the animal’s body on land.

An early split in the tetrapod tree (see Figure 32.10) led to two main groups of terrestrial vertebrates: amphibians, most of which remained tied to moist environments, and the amniotes, many of which adapted to much drier conditions.